Symbol of Yin and Yang. Yang - white, masculine, emphasis on the external; Yin is black, feminine, emphasis on the inner.

Yin and yang (Chinese trad. ‰A-z, ex. ??, pinyin: yon yбng; Japanese in-yo) - one of the main concepts of ancient Chinese natural philosophy.

The doctrine of yin and yang is one of the theoretical foundations of traditional Chinese medicine. All phenomena of the surrounding world, including humans and nature, are interpreted by Chinese medicine as the interaction between the two principles of yin and yang, representing different aspects of a single reality

Philosophical concept

In the “Book of Changes” (“I Ching”), yang and yin served to express the light and dark, hard and soft, male and female principles in nature. As Chinese philosophy developed, yang and yin increasingly symbolized the interaction of extreme opposites: light and dark, day and night, sun and moon, sky and earth, heat and cold, positive and negative, even and odd, etc. Purely abstract meaning yin-yang was obtained in the speculative schemes of neo-Confucianism, especially in the doctrine of “li” (Chinese vX) - the absolute law. The concept of the interaction of the polar forces of yin-yang, which are considered as the main cosmic forces of movement, as the root causes of constant variability in nature, constitutes the main content of most dialectical schemes of Chinese philosophers. The doctrine of the dualism of yin-yang forces is an indispensable element of dialectical constructions in Chinese philosophy. In the V-III centuries. BC e. In ancient China there was a philosophical school called Yin Yang Jia. The concept of yin-yang has also found various applications in the development of the theoretical foundations of Chinese medicine, chemistry, music, etc.

Discovered in China several thousand years ago, this principle was originally based on physical thinking. However, as it developed, it became a more metaphysical concept. In Japanese philosophy, the physical approach has been preserved, so the division of objects according to yin and yang properties is different between the Chinese and the Japanese. In the new Japanese religion oomoto-kyo, these are the concepts of the divine Izu (fire, yo) and Mizu (water, in).

The single primordial matter of taiji gives rise to two opposite substances - yang and yin, which are one and indivisible. Initially, “yin” meant “northern, shadowy”, and “yang” meant “southern, sunny slope of the mountain.” Later, yin was perceived as negative, cold, dark and feminine, and yang as positive, light, warm and masculine.

The Nei Ching treatise says on this matter:

Pure yang substance is transformed into the sky; the muddy substance of yin is transformed into the earth... The sky is the substance of yang, and the earth is the substance of yin. The sun is the substance of yang, and the moon is the substance of yin... The substance of yin is peace, and the substance of yang is mobility. The yang substance gives birth, and the yin substance nurtures. The yang substance transforms the breath-qi, and the yin substance forms the bodily form.

Five elements as a product of Yin and Yang

The interaction and struggle of these principles give rise to the five elements (primary elements) - wu-xing: water, fire, wood, metal and earth, from which arises the entire diversity of the material world - “ten thousand things” - wan wu, including man. The five elements are in constant movement and harmony, mutual generation (water gives birth to wood, wood - fire, fire - earth, earth - metal, and metal - water) and mutual overcoming (water extinguishes fire, fire melts metal, metal destroys the tree, the tree destroys the earth, and the earth fills up the water).

Pictographic letter

Pictographic letter- a type of writing, the signs of which (pictograms) indicate the object they depict.

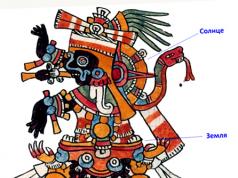

Rice. 1. Aztec pictogram " World

" from Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

Rice. 1. Aztec pictogram " World

" from Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

Pictographic letter used at the dawn of writing by different cultures: Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Chinese, Aztec, etc.

Pictographic writing was preserved among the only people- Naxi, living in the foothills of Tibet.

In theory, inscriptions in pictographic script can be understood by people speaking different languages, even if the pictographic scripts of those languages are different.

Pictographic writings contain thousands of characters. The complexity and limitations of the system (it can only describe objects) explain the movement of such systems towards ideographic writing. This movement is accompanied by an expansion of the meaning of signs, as well as simplification and canonization of the outline of each sign.

Examples of pictographic writing- Codes of the Indians of Mesoamerica.

The age of Chinese writing is constantly being clarified. Newly discovered inscriptions on shells turtles, resembling the oldest Chinese characters in style, date back to the 6th millennium BC. e., which is even older than Sumerian writing.

Chinese writing is usually called hieroglyphic or ideographic . It is radically different from the alphabetical one in that each sign is assigned a meaning ( not only phonetic), and the number of characters is very large (tens of thousands).

Background

The oldest Chinese records were made on tortoise shells and cattle shoulder blades, and recorded the results of fortune telling. Such texts are called jiaguwen (甲骨文). The first examples of Chinese writing date back to the last period of the Shang Dynasty (the most ancient - to the 17th century BC).

Later, the technology of bronze casting arose, and inscriptions appeared on bronze vessels. These texts were called jinwen (金文). The inscriptions on bronze vessels were previously extruded onto a clay mold, there was a standardization of hieroglyphs, they began to fit into a square ».

COMMENT 1:

Now consider a brief description of the concept and symbol DAO. Here's what the work says about Taoism:

« Taoism- a bizarre phenomenon, different, like a patchwork quilt. This is not a religion, not a doctrine, not a philosophy, not even a conglomerate of schools. Rather, it is a special mood of consciousness inherent in the Chinese ethnic group. If Confucianism is how the bearers of this tradition think about themselves, then Taoism is what they really are, and these parts of the “I” - the real “I” and the ideal “I” - are indissoluble and are obliged to live together .

Taoism is a somewhat arbitrary term, as the Confucians called all those people - and there were many of them - who “talked about Tao.” They could perform different rituals and adhere to different types of practices, be healers, healers, magicians, and wandering warriors.

Taoism left behind a considerable number of symbols that are associated with the most ancient, most archaic ideas about spirits, « floors» Sky, traveling to the afterlife and communicating with ancestors. Taoism still widely uses a peculiar " secret writing“, so reminiscent of the magical signs of shamans, is a system of slightly modified hieroglyphs that, when written, for example, on the wall of a house or on colored paper, influence the world of spirits in a certain way...

Taoism would have long remained the main exponent of the magical teachings of China, if not for Buddhism. It was Buddhism that forced Taoism to transform from an amorphous movement of “magicians” and “immortals,” that is, mediums and fortune-tellers, into a fully formed teaching with a powerful religious complex. It included a system of rituals and worship, clearly established, although with a somewhat amorphous pantheon of gods. Buddhism came to China in the 1st-3rd centuries. as a ready-made and relatively coherent teaching - here it was opposed by a bizarre conglomerate of beliefs and mystical experiences, called Taoism.

And it was Buddhism that interrupted the rise of Taoist mysteriology, forcing her, on the one hand, to “land” to rationalism. This was expressed, first of all, in the creation of numerous texts explaining mystical doctrines, and on the other hand, “rising” to one of the main ideological systems of imperial China. Thus, as a relatively integral complex of beliefs, rituals and schools with its patriarchs, Taoism emerged quite late. In any case, later than Chinese historiographers write. Back in the 3rd century. BC. Taoism under Qin Shihuang receives official institutionalization. It is recognized by the imperial court as one of the court teachings, and in the 2nd-3rd centuries. already appears as a very influential movement at court, and this “external” or “visible” part of it turned out to be entirely subordinated to the interests of the court and the highest aristocracy, for example, it satisfied the interest in prolonging life, predicted by the stars and sacred signs. The mystical knowledge of Taoism was reduced only to particular techniques, which then became associated with Taoism in general.

Buddhism itself has adopted a lot from Taoism, first of all, terminology and many forms of practices, but at the same time it makes Taoism realize itself as something holistic and harmonious. Moreover, not only Buddhism sinicized, having entered the borders of the Celestial Empire, but also Taoism " Buddhistized“, and this “Buddhization” continued for many centuries. The Taoists adopted from the Buddhists... many methods of meditative practice, reading established prayers and daily routines; they were attracted by Buddhist drawn symbols - and Taoism had its own “mandala”: the famous black and white “fish” Yin and Yang. (We considered the principle of construction in the matrix of the Universe "mandalas" - "monads"in an article on the website— The secret of the location of the Great Limit and the Monad of the Chinese sages in the matrix of the Universe).

In the XII-XIII centuries. In Taoism, which previously practically did not recognize monks, the institution of monasticism appears. For monks, vows are required and monastic rules are imposed - all of which also comes from the highly developed monastic doctrine of Buddhism.

It is this absolute flexibility that has allowed Taoism to take on a variety of forms and incorporate many methods of spiritual practice. For example, Taoism actively interacted with legalism (“ doctrine of the lawyers"). It is no coincidence that in ancient texts the term “ Tao» ( Path) is often replaced by the term F — « by law" or " method"precisely in the meaning that is meant by it in legalism, and in particular in the “Four Books of Huang Di” (“Huang Di Si Jing”), discovered during excavations in Mawangdui near Changsha in the 70s. last century...

Formally, from the point of view of worship and rituals, the Taoist pantheon is headed by either the “Heavenly Ancestor” (Tianzong) or the “Ruler of Tao” (Daojun), often associated with Laojun (“Ruler of Lao”), the deified Lao Tzu. It is his image that occupies the central part of the altars in churches, is placed in home shrines, and incense is regularly burned to him.”

Next, consider the ancient Chinese pictogram denoting the concept of Tao, corresponding to it hieroglyph, and their connection with the matrix of the Universe. The view of the pictogram, whose age is 2000 BC, and the hieroglyph taken from the work. Figure 2 on the left shows the original images of the hieroglyph and pictogram, which I combined with the matrix of the Universe at the transition point between the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix.

Rice. 2. The picture on the left (below) shows the original images of the icon Tao and the type of hieroglyph accepted today Tao(up). As you can see, it is asymmetrical, but the pictogram is more symmetrical. I combined the original hieroglyph and pictogram Tao with the matrix of the Universe at the place of transition between the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix. Below right is the view of the icon I edited. At the top right is shown my proposed view of the symmetrical hieroglyph of Tao. In my opinion, its appearance more accurately corresponds to the ancient pictogram Tao and symmetrical processes occurring in the matrix of the Universe. Moreover, the cross and the base of the upper step at the top of the proposed character correspond to the Chinese character That- "Earth". In addition, this form of the Dao hieroglyph, in its central part, is almost similar to the Egyptian hieroglyph – Maaqet ( staircase of Osiris), which we considered in our work on the site - In a dream, Jacob saw a staircase leading to heaven, in the matrix of the Universe! According to the views of the ancients - “ Tao – this is the path that Nature creates and Society must follow" From considering the results of combining the original hieroglyph of Tao and the pictogram of Tao with the matrix of the Universe, it becomes clear to us that the Chinese hieroglyph and pictogram were initially created according to the laws of the matrix of the Universe, which acted as the basis for their creation.

Rice. 2. The picture on the left (below) shows the original images of the icon Tao and the type of hieroglyph accepted today Tao(up). As you can see, it is asymmetrical, but the pictogram is more symmetrical. I combined the original hieroglyph and pictogram Tao with the matrix of the Universe at the place of transition between the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix. Below right is the view of the icon I edited. At the top right is shown my proposed view of the symmetrical hieroglyph of Tao. In my opinion, its appearance more accurately corresponds to the ancient pictogram Tao and symmetrical processes occurring in the matrix of the Universe. Moreover, the cross and the base of the upper step at the top of the proposed character correspond to the Chinese character That- "Earth". In addition, this form of the Dao hieroglyph, in its central part, is almost similar to the Egyptian hieroglyph – Maaqet ( staircase of Osiris), which we considered in our work on the site - In a dream, Jacob saw a staircase leading to heaven, in the matrix of the Universe! According to the views of the ancients - “ Tao – this is the path that Nature creates and Society must follow" From considering the results of combining the original hieroglyph of Tao and the pictogram of Tao with the matrix of the Universe, it becomes clear to us that the Chinese hieroglyph and pictogram were initially created according to the laws of the matrix of the Universe, which acted as the basis for their creation.

To confirm our previous conclusions that the matrix of the Universe was the sacred basis for the creation of Chinese hieroglyphs, I will give another example of combining the Chinese character - Hui - with the matrix of the Universe. Dicks). Its translation from Chinese means “”.

Rice. 3. On the image A- Chinese character Hui is shown - ( X ui

)

, combined with the matrix of the Universe. Its translation from Chinese means - return, turn back. This is what the Chinese say and write in our “ Visible

» world. However, the same hieroglyph, placed in the matrix of the Universe, will denote similar concepts, but in “ The invisible world

" The concept " return, turn back" will denote movement from the Lower World to the Upper World of the matrix, where " home

"spiritual beings are returning. From the picture it is clear that the hieroglyph is located at the transition point between the Upper and Lower worlds. At the same time, it seems to be shifted towards the Upper World. The lines of the hieroglyph pattern are combined with eight (light circles) positions of the Upper World and only four positions (dark circles) of the Lower World. The dotted arrow on the left shows the direction " arrival

» in the lower world of the matrix, and the solid arrow on the right shows the direction “ exit

» from the Lower World to the Upper World. It is clearly seen from the figure that this hieroglyph was created on the basis of the matrix of the Universe and it was in it that, when created, it primarily denoted the concept - “ Go back, turn back O" The same meaning and appearance of this hieroglyph was extended to describe similar concepts in the everyday life of man and society in “ visible world

».

Rice. 3. On the image A- Chinese character Hui is shown - ( X ui

)

, combined with the matrix of the Universe. Its translation from Chinese means - return, turn back. This is what the Chinese say and write in our “ Visible

» world. However, the same hieroglyph, placed in the matrix of the Universe, will denote similar concepts, but in “ The invisible world

" The concept " return, turn back" will denote movement from the Lower World to the Upper World of the matrix, where " home

"spiritual beings are returning. From the picture it is clear that the hieroglyph is located at the transition point between the Upper and Lower worlds. At the same time, it seems to be shifted towards the Upper World. The lines of the hieroglyph pattern are combined with eight (light circles) positions of the Upper World and only four positions (dark circles) of the Lower World. The dotted arrow on the left shows the direction " arrival

» in the lower world of the matrix, and the solid arrow on the right shows the direction “ exit

» from the Lower World to the Upper World. It is clearly seen from the figure that this hieroglyph was created on the basis of the matrix of the Universe and it was in it that, when created, it primarily denoted the concept - “ Go back, turn back O" The same meaning and appearance of this hieroglyph was extended to describe similar concepts in the everyday life of man and society in “ visible world

».

Figure 4 shows a photograph of two sides of a Chinese coin. In its center there is a characteristic square hole. Let's explore these coin drawings, combining them with the matrix of the Universe.

Rice. 4. The picture shows a photograph of two sides of a Chinese coin. In its center there is a characteristic square hole. As a rule, Chinese coins had an image on only one side.

Rice. 4. The picture shows a photograph of two sides of a Chinese coin. In its center there is a characteristic square hole. As a rule, Chinese coins had an image on only one side.

Rice. 5. The figure shows the result of combining the left side of the coin shown in Figure 4 with the matrix of the Universe. The inner circle of the coin is highlighted " bold circle”, which passes through the 4th level of the Upper and Lower worlds of the Matrix, within which two sacred Tetractys are located. The dragons' bodies are positioned head down. Between them there is a circular ledge with " rays

", the center of which is exactly aligned with the top of the pyramid of the Upper World and is highlighted in the figure on the left and right with a white circle. Sides " square” in the center of the coin aligned with two positions of the 2nd level of the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix. It is clearly seen from the figure that the matrix of the Universe was the initial basis for creating the proportions of the coin and the drawings on it.

Rice. 5. The figure shows the result of combining the left side of the coin shown in Figure 4 with the matrix of the Universe. The inner circle of the coin is highlighted " bold circle”, which passes through the 4th level of the Upper and Lower worlds of the Matrix, within which two sacred Tetractys are located. The dragons' bodies are positioned head down. Between them there is a circular ledge with " rays

", the center of which is exactly aligned with the top of the pyramid of the Upper World and is highlighted in the figure on the left and right with a white circle. Sides " square” in the center of the coin aligned with two positions of the 2nd level of the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix. It is clearly seen from the figure that the matrix of the Universe was the initial basis for creating the proportions of the coin and the drawings on it.

Rice. 6. The figure shows the result of combining the right side of the coin shown in Figure 4 with the matrix of the Universe. The inner circle of the coin is highlighted " bold circle”, which passes through the 4th level of the Upper and Lower worlds of the Matrix, within which two sacred Tetractys are located. The tops of the pyramids of the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix aligned exactly with the centers of the upper and lower hieroglyphs depicted on the coin. These locations are shown with white circles. It is clearly seen from the figure that and for this side of the coin the matrix of the Universe was the initial basis for creating the proportions of the coin and the patterns of hieroglyphs on it.

Rice. 6. The figure shows the result of combining the right side of the coin shown in Figure 4 with the matrix of the Universe. The inner circle of the coin is highlighted " bold circle”, which passes through the 4th level of the Upper and Lower worlds of the Matrix, within which two sacred Tetractys are located. The tops of the pyramids of the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix aligned exactly with the centers of the upper and lower hieroglyphs depicted on the coin. These locations are shown with white circles. It is clearly seen from the figure that and for this side of the coin the matrix of the Universe was the initial basis for creating the proportions of the coin and the patterns of hieroglyphs on it.

Based on the results of combining the two sides of the coin, we can clearly conclude that the matrix of the Universe was the initial basis for creating the proportions of the coin and the drawings on it. Thus, the matrix of the Universe, as the basis of the Universe and the basis for the creation of writing, including hieroglyphics, was known to the ancient Chinese sages as well as to the Egyptian priests, priests of ancient India, priests of ancient Iran, the ancient Slavs, the ancient Greeks, and the ancient Jews.

COMMENT 2:

Along with the Chinese character Tao consider Indian sacred symbol AUM (OM). Next, let's compare these two symbols, combining them with the matrix of the Universe. Let us give a brief description of the Sacred Symbol from literary sources. AUM (OM). Harish Johari writes in the section “AUM - The Essence of All Mantras”:

“The Chandogya Upanishad says:

The essence of all existence is earth.

The essence of earth is water.

The essence of water is plants.

The essence of plants is man.

The essence of man is speech.

The essence of the speech is the Rig Veda.

The essence of the Rig Veda is Samveda.

The essence of Samveda is udgita(i.e. AUM) .

Udgita- the best of essences, deserving the highest place.

Rice. 7. Visually –AUM (OM) represented by a pictogram.

Rice. 7. Visually –AUM (OM) represented by a pictogram.

Thus, in all texts of Vedic origin AUM(or OM) is the essence of everything. AUM is a single whole, personifying the all-encompassing cosmic consciousness, turiya, the fourth-dimensional consciousness that goes beyond words and concepts, pure self-existence.

The Upanishads say that AUM is Brahman itself, that is, “God in the form of sound is AUM (OM).”

Pranava (AUM) is a bow,

The arrow is a personality

The goal is Brahman.

The Maitreya Upanishad compares AUM with an arrow that manas(mind, thinking, reason) lays on the bow of the human body ( breathing); Having pierced the darkness of ignorance, this arrow reaches the light of the highest state. Just as a spider climbs its web and achieves freedom, yogis rise to liberation through the syllable AUM.

AUM represents the original sound of timeless reality, which eternally vibrates in a person and is repeatedly reflected in his entire being. This sound reveals the innermost essence of a person to the vibration of a higher reality - not the reality that surrounds a person, but the endless reality that is eternally present both inside and outside.

The poet Rabindranath Tagore beautifully described this sacred syllable when he said that AUM is a word-symbol of the perfect, infinite and eternal. This sound is perfect in itself and represents the integrity of all things. Any religious contemplation begins with AUM and ends with this syllable. The purpose of this is to fill the mind with a sense of infinite perfection and liberate it from the world of limited selfishness.

The phenomenal world is created by different frequencies. According to all spiritual teachings, God first created sound, and from these sound frequencies the phenomenal world arose. Our entire existence consists of this sound. When this sound is ordered by the desire to communicate, manifest, evoke, materialize, excite or fill with energy, it turns into “ mantra ».

Rice. 8. The figure shows two sacred symbols of different cultures - ancient India and ancient China, combined with the matrix of the Universe at the transition point between the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix. Both characters " get married

"foundation of the Upper World as a place" last step

"in front of the Lower World of the matrix of the Universe. Their semantic meaning is an indication of “ primacy

» The Upper World above the Lower World of the Matrix. Left, A–Vedic symbol AUM (OM). On right, IN– the type of symmetrical hieroglyph and concept I propose – DAO. Basic elements of both symbols OM And DAO pass through the same positions of the Upper World of the matrix. But, unlike the symbol OM, which touches with an arc only the top of the pyramid of the Lower World, symbol DAO more " covers

"or passes through all six upper positions of the Lower World of the matrix. In this sense, the symbol DAO indicates significance and " character

» processes at the place of transition from the Upper world of the matrix to the Lower world. It is clearly seen from the figure that both symbols were constructed according to the laws of the matrix of the Universe and describe or reflect the processes occurring in this “ The invisible world

».

Rice. 8. The figure shows two sacred symbols of different cultures - ancient India and ancient China, combined with the matrix of the Universe at the transition point between the Upper and Lower worlds of the matrix. Both characters " get married

"foundation of the Upper World as a place" last step

"in front of the Lower World of the matrix of the Universe. Their semantic meaning is an indication of “ primacy

» The Upper World above the Lower World of the Matrix. Left, A–Vedic symbol AUM (OM). On right, IN– the type of symmetrical hieroglyph and concept I propose – DAO. Basic elements of both symbols OM And DAO pass through the same positions of the Upper World of the matrix. But, unlike the symbol OM, which touches with an arc only the top of the pyramid of the Lower World, symbol DAO more " covers

"or passes through all six upper positions of the Lower World of the matrix. In this sense, the symbol DAO indicates significance and " character

» processes at the place of transition from the Upper world of the matrix to the Lower world. It is clearly seen from the figure that both symbols were constructed according to the laws of the matrix of the Universe and describe or reflect the processes occurring in this “ The invisible world

».

Each of us has seen symbol of the Taoist monad, but not everyone thought about the meaning of the black and white dots located in the center of the black and white areas. Ancient Chinese mythology says that Yin - Yang is a symbol of the creative integrity of diametricalities in the Universe. It is depicted in the form of a circle, which symbolizes the image of infinity. This circle is divided into two halves by a wavy line. One part is black, the other is white.

Inside the circle are symmetrically located two points: white on a black background and vice versa, black on white. These points tell the story that the two great forces of the universe carry within them the birth of opposition. Black and white fields means Yin and Yang, they are also symmetrical, but their symmetry is not static. Thanks to this symmetry, a continuous cycle occurs, and when one of the principles has reached its apogee, it is ready to retreat: “Yang, reaching the peak of its development, retreats before Yin. Yin, reaching its peak of development, retreats before Yang.”

Yin and Yang- these are two opposite and interchangeable principles that permeate the entire Chinese culture. The ancient Chinese believed that all manifestations of Tao were generated through the interaction of two diverse forces.

The division of Heaven and Earth was preceded by the primordial integrity of the world. Chaos was called the beginning of everything that exists. For the creation of the world, chaos had to disintegrate. It dissociated into 2 main elements: Yin and Yang.

Originally, Yin and Yang meant the dark and light sides of the mountain. From one point of view, they represented only different slopes of the mountain; from another, they were no different from each other. Their qualitative difference can be determined by a certain force, the sun, which illuminates both slopes in turn.

Yin and Yang correspond to the elements such as fire and water. The cycle of these elements includes 2 stages, which are symbolized with the elements of metal and wood. Thus, a transformation circle of Yin and Yang is formed, which has its own center. Emblem center of the circle- This is the element of Earth. Thus, a fivefold structure unfolds, combining Yin and Yang with the triad of creation, and therefore is a symbol of the universe.

The hieroglyph “dao” serves in ancient Chinese and modern Chinese to denote the most important concept of Chinese civilization, defined in the third verse of the canonical version of the text “Tao Te Ching” as the predecessor of the ancestor “di”: “The emptiness of dao in application is not overflowing. Oh, how deep is [his] abyss! Like the head of the family of the founder of ten thousand things. Oh, how abundant! Similar to what their existence contains. I don't know whose child she is. It precedes the image of the [first] ancestor - di.” 2 A semiotic analysis of this concept gives grounds to assert that it reflects the most important concept for Chinese philosophy and mythology, related to the description of the world through an anthropomorphic image, the image of a person.

1 See: doctoral dissertation of Martynenko N.P. "Specificities of the semiotic study of ancient Chinese texts." M., 2007. pp. 352-372. Abstract:

2 Lao Tzu. Tao Te Ching (“Foundation of Tao Te”). Zhuzi baijia zhi daojia (“Collected works of all schools of philosophers - the school of Taoists”). Beijing. 2001. P. 8.

In the history of Taoism, the myth of the anthropomorphic universe was reflected in the idea of Lao-jun as a world man. The image of Lao Tzu underwent a similar transformation, which from a real historical character subsequently also transformed into the image of a world man. In the history of Taoism, there is an argument in favor of correlating the concept of “Tao” and the mythological concept of “Pan-gu”. Taoist schools developed a detailed historiography of the Tao, tracing it back to the sacred ancestors. Thus, in the anthology “Yun ji qi pian” in the section “On the roots of the teachings of Tao” it is said that as a teaching it appeared under the three august lords - members of the supreme triad of the Taoist pantheon - Pan-gu, Huang-di, Lao-tzu, and five first ancestors. 3 Thus, the Taoists directly traced the beginning of their teaching about Tao to the image of Pan-gu.

3 Torchinov E. Taoism. St. Petersburg, 1993, p. 134.

In the four-volume “Big Chinese-Russian Dictionary”, published under the editorship of I.M. Oshanin, in the article dedicated to the hieroglyph “dao”, more than a hundred lexical meanings of this hieroglyph are given - words belonging to different grammatical categories, parts of speech, etc. This polysemy causes the intractable problem of choosing from all this verbal diversity the word that most adequately conveys the meaning of the ideographic sign. It takes on such lexical meanings as “road”, “speak”, “feel”, “express”, “counting word for official papers”, “should”, “should”, “gender morpheme to denote parts of the body”, etc. 4 For a native speaker, for example, Russian, these are completely different, irreducible meanings. The wide variety of meanings of this hieroglyph provides a wide field for its interpretation. Reducing its meaning to just one of the vast complex of available lexical meanings is not enough to express it. This creates an intractable problem of adequately choosing a meaning for its translation into European languages, which was discussed in detail in the first chapter of this work. To resolve this problem, a detailed study of the etymological meanings of the hieroglyph in correlation with the complex of its lexical meanings is necessary to identify and understand the process of development of the concept.

4 Large Chinese-Russian Dictionary: In 4 volumes. T. 4. M., 1983. P. 96.

Forms of the hieroglyph “dao”

In the Jin Wen inscriptions:

In the inscriptions "gu wen":

In the zhuan wen inscriptions:

Variants of modern forms of writing the hieroglyph “dao”:.

As already mentioned, the hieroglyph “xing” included in the “Dao” sign takes on the meaning “to walk.” In "Shouwen Jiezi" it is defined as meaning: "a person who walks quickly." 5 The second element, “show,” means “head.” Together, these two hieroglyphs give reason to assume the following reconstruction of the prototype of the hieroglyph “dao” - this is an image of a walking man:

5 Xu Shen Zhuan, Xu Xuan Jiaoding. (Essay by Xu Shen, revised by Xu Xuan) Showen Jiezi (Explanation of Wen and Interpretation of Zi). Shanghai: Jiaoyong Chubanshe. 2004. P. 51.

From this image we can derive stylized and schematized ancient forms of the hieroglyph “Tao”.

The left side of the hieroglyph "xing" is "chi", which separately means: "step with the left foot." The right part of “chu”: “short step with the right foot.” In writing, both parts could be interchanged. Together, “chi” and “chu” mean “chi chu”: “to walk slowly, step over one’s feet.” In many ancient hieroglyphs, the "chi" sign was interchangeable with the "cho" sign, which represented three features of the "chi" sign on top, complemented below by the "zhi" sign, derived from the image of "foot" (ancient meanings of "foot", "stand" "), realistically denoting the action “to step” and taking the meaning: “to take a step, step, step over”; “walk and stop, walk (run) with stops.” 6 The sign “cho” (the abbreviated form of the outline - ) is included in the modern, most common, form of the outline of the hieroglyph “dao”. In turn, the oldest complete forms of the “dao” hieroglyph (preserved to this day as alternative forms) included the “xing” sign, also supplemented below with a “foot” pattern, and sometimes a “hand” pattern. All together this pointed to the image of a “walking man”, setting the meaning: “a man who walks quickly.” 7 The hieroglyph “xing” is key in the definition of the hieroglyph “dao” in the dictionary “Shouwen Jiezi”, where it is characterized by the phrase “so xing”. The translation of this definition can be twofold. Translating the hieroglyph “sin” with the word “to walk” does not cause any particular difficulties. But, depending on the different translation options for the hieroglyph “so,” the meaning of this combination of signs can be understood differently. In ancient Chinese, the character “so” can take on two service meanings. It can form a nominal complex with the subsequent verb, denoting the object of action of this verb, and is translated by pronouns: “the one whom” or “that” in various cases with various prepositions 8. It was also used as a function word, which, if it comes before a verb, objectifies it and forms with it a noun phrase with a hint of pronominal demonstrativeness. 9 The phrase “so sin” can have two translations: 1) “that [on which] they walk”, in the understanding - “road, path”; 2) “the one [who] walks”, in the sense of “walking”. The latter translation, in our opinion, more accurately conveys the definition of the character “dao” in “Shouwen Jiezi” and is in good agreement with the meaning of the character “xing”.

6 Karlgren B. Grammata Serica. Script and Phonetics in Chinese and in Sinu-japanese. Reprinted from the Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Stockholm. No. 212, 1940, p. 312.

7 Gao Heng. Wenzi xingyixue gailun. Jinan. 1963. P.115.

8 Large Chinese-Russian dictionary in 4 volumes. edited by I.M.Oshanina. M., Science, vol. 2, 1983, p. 733.

9 Kryukov M.V., Huang Shu-ying. Ancient Chinese language. M., 1978, p. 163.

However, the reconstructed prototype of the hieroglyph “dao” is the image of a walking man, conditionally. Conventionally, because in life we see it from the inside - “inside out”. The shapes of the hieroglyph “dao” apparently go back to the image of what and how a person sees while walking. The outline of this hieroglyph is based on the image of the details of the subjective perception of the posture of the human body in the process of walking, taking a step forward, bringing out the foot and hand, which fall into the pedestrian’s field of vision. In the process of vision, the whole body is involved in movement, that is, we see the world not just with our eyes, but with the eyes located in the head, the head is on the shoulders, and the shoulders are part of the body of a person who is able to move, waving his arms and stepping with his legs. 10 In the ancient forms of writing the hieroglyph “dao”, visual information is recorded that specifies the proximity of the observer’s body parts in relation to the observation point (which is located approximately in the area of the nose in front of our eyes and in Chinese is denoted by the hieroglyph “zi” - “nose”) - closer In total there is a head, then a torso, limbs, fingers. This is what the character "dao" represents, which explains the use of the character "dao" in the Middle Ages in Chinese as a "gender morpheme for words denoting parts of the body." The fact that the outline of the hieroglyph “dao” depicts vision - the experience of one’s body, also explains such lexical meanings as: “to feel”, “to sense”.

10 Gibson J. An ecological approach to visual perception. M., 1988., p. 178-179.

The complex of these lexical meanings can be explained by clarifying the etymological meaning of “dao”, for which we consider its second element - the hieroglyph “show”. The sign for "show" includes two other meaningful elements: "zi" and . The hieroglyph “zi” takes on the meaning “nose”, and also acts as a “personal pronoun”. To understand the internal connection between these two meanings, you need to know that when the Chinese talk about themselves in person, they point to their nose. Thus, for the Chinese, the nose is a point of reference to oneself. Starting from the language of the inscriptions on the Shang-Yin oracle bones, the starting point of reference for movement in space and time was introduced through the sign “Zi”, and in this function it could not be omitted without compromising the meaning 11 . When translating texts of the Zhou period, this hieroglyph is also given the meaning of a personal pronoun of the first person, and a word-forming particle corresponding to the prefixes: “self-, auto-”; or: “by itself, from itself, by itself, on its own; naturally, without a doubt." The hieroglyph “zi” includes another significant element: “mu”, derived from the image of the eye - the oval of the eye socket, the eye and the pupil. Subsequently, the style was shortened to . In accordance with this sign depicting an eye, dictionaries list an extensive complex of lexical meanings: “eye, eyes; look, look; look, follow with eyes, express dissatisfaction with a glance; index, title, title, chapter, order; title, chief, senior,” from which it becomes clear that this hieroglyph indicates the eyes as an organ of vision, an exponent of the internal state of a person and their actualization in vision, as well as in the management, management and ordering of visual ideas. In turn, the hieroglyph “zi” depicts an invariant of visual perspective, significant for any person and indicates the point from which it unfolds. The vocabulary complex of meanings of this sign is determined by the life experience of a sighted person, described in detail in the works of J. Gibson, who for many years dealt with the problem of analyzing visual perception and in the course of research came to the following understanding. Each of the two eyes of a person, occupying its own point of observation, carries out its own selection from its comprehensive visual system and they overlap each other. The closest boundary of the field of view is determined by the oval of the eye socket and the edge of the nose. Since the two eyes, as two points of observation, are slightly separated, a disparity or unpairedness of the two visual structures arises, maximum for the contour, which is the projection of the edge of the nose. The edge of the nose is the leftmost projection that the right eye sees and the rightmost projection that the left eye sees. This maximum unpairedness contains information about zero distance, that is, information about the awareness of “oneself” in the center of the arrangement of surfaces extending into the distance. The nose, projected in maximum proximity, provides an absolute reference point, zero distance measured “from here” and sets the visual-spatial experience of “oneself”. 12 These features of human visual perception explain the complex meanings of the hieroglyph “tzu”: 1) nose; 2) the starting point of movement in space and time; 3) personal pronoun of the first person; 4) word-forming particle corresponding to the prefixes: “self-, auto-”; or: “by itself, from itself, by itself, on its own; naturally, without a doubt." In the structure of human visual perception, the nose is the origin of coordinates, the place “from here” and provides the basis for the visual-spatial experience of “oneself-in-the-world”, which is also conveyed in the Russian expression “personal pronoun”, which can be literally understood as “ having the place of one’s own person.”

11 Kryukov M.V., Huang Shu-ying. Ancient Chinese language. M., 1978, p. 28, 30.

12 Gibson J. An ecological approach to visual perception. M., 1988B p. 178-179.

The hieroglyph “zi” carries the meaning of a reference system coordinated with a person, the source both for visual empathy of “oneself” and for visual-spatial perception and assessment by eye parallax of the location and distance of objects, as well as the depth of space. The hieroglyph “tzu” denotes the starting point of perception, localized in the area of the “optical window” and the nose. In turn, this initial visual image is also important for understanding the self-perception of the head and face, the experience of which is reflected in the meanings of the hieroglyph “show”, consisting of the hieroglyph “zi”, to which is added an ideogram with the meaning: “hair (all facial hair), eyebrows, hair on the top of the head.” In dictionaries, the following meanings are given in accordance with the hieroglyph “show”: “face, outer side, show (on); head, turn your head, turn around; bow your head, submit; introduce, begin, initiate, leader; based on; manifest, express" 13. The hieroglyph “show” depicts and indicates some details of one’s own face that fall into the person’s field of vision. The complex of its meanings is easy to explain if we take into account the fact that self-perception of the head and head movements are recorded not only by the vestibular apparatus of the inner ear, but also visually. That is, when a person turns his head, he also looks around. When the head moves, the world is hidden and revealed in such a way that there is complete correspondence between the movement of the head and the change in the visible world. This corresponds to the principle of reversible correspondence: whatever is out of sight when the head is raised comes into view when the head is lowered, etc. Thus, the basis of the ancient forms of the hieroglyph “Tao” is the image of a walking man from the “inside” perspective.

The angle of the image contained in the hieroglyph “Tao” was, as it were, a view from the inside, i.e., how a person taking a step sees himself, with this angle the entire world around him comes into the person’s field of vision. This circumstance determined that this image of a walking man began to denote not only the man himself and the meanings derived from this image, but also the place along which he walks: “road”, “path” and even what surrounds the traveler - “district” , expressed in the lexical meaning of “unit of administrative division”. Further expansion of the lexical meanings of the hieroglyph “dao” followed the path of acquiring more abstract meanings: “path of a celestial body”, “orbit”; “path as a direction of activity”, “approach”, “method”, “rule”, “custom” and even acquired such meanings as “technique”, “art”, “trick”, “trick”. There was also an acquisition of epistemological meanings: “idea”, “thought”, “teaching”, “dogma”. Its ontologization also took place, expressed in lexical meanings: “true path”; "highest principle"; “omnipresent principle”, “universal law”, “source of all phenomena”. All of the above lexical meanings of the hieroglyph “dao” are given in the fundamental Chinese-Russian dictionary edited by I.M. Oshanina. 14

14 Large Chinese-Russian dictionary in 4 volumes. edited by I.M.Oshanina. M., Science, vol. 2, 1983, p. 636.

The image of body movement coordination when walking also explains such lexical meanings as “calculate”, “think”, “know”, which the hieroglyph “dao” takes. Research into the connections between sign language and human thinking shows their close relationship. 15 Such a relationship should also take place in relation to the most familiar pattern of movement - stepping. An example of this is one of the lexical meanings of the full form of the hieroglyph “dao”, translated into Russian with the words “lead”, “leader”. The Russian word “to guide” can be understood as a derivative of “to lead with a hand,” which most directly correlates with the way a person controls his movements, stepping with his feet and waving his arms in a coordinated manner. Further expansion of the lexical meanings of the hieroglyph, the less complete form of the hieroglyph - “dao” is recorded in its following ancient lexical meanings: “to pass”, “to keep the path from”, “to lead”, and then “to make a sacrifice to the spirit of the road - the patron saint of travelers "

The “passing vision [as if from within] by a person in motion” recorded in “Tao” has another “side” that is very difficult to comprehend. It indicates the unity of the body and the world around it, which is realized in visual perception, feeling and awareness. A person’s vision of himself is always accompanied by a vision of the world around him, i.e., at the same time, the world around him also comes into view. In this visual construction, a person and the world around him are complementary, or, in other words, the visible world and the viewer also exist conditionally as up and down, left and right. Self-perception and a person’s perception of the world occur simultaneously, being only poles of attention, and what a person turns his attention to depends only on his attitudes. The image recorded in the hieroglyph “Tao” is so ordinary for any walking person that they usually do not pay attention to it, although it is constantly in the field of our attention. But it is precisely this image that is the main and fundamental condition of human life. The visible meaning of the graphic structure of the hieroglyph “dao” suggests that a person and the world around him are complementary, the visible world and the viewer coexist just like up and down, left and right. In asserting this, we rely on the fact that a person’s perception of himself and a person’s perception of the world are equally present in direct sensory data, being poles in the spectrum of attentional settings.

The hieroglyph “Tao” focuses a person’s attention on certain aspects of his holistic vision. The most important part of the surrounding world is the observer himself: a person’s field of vision always includes both his body and the world around him, for example, the sky above his head and the earth under his feet. This visual image underlies the fundamental idea for Chinese philosophy that “Tao is a triad - heaven, earth, man” 16. This definition is completely natural within the framework of the above-described visually perceived position of observing a person standing on the ground under the sky and seeing them against the background of the contours of his body. The contours of the body in this case are the boundary between the internal and external image of perception, acting as the middle element of the unity of perception within which the life of a person passes as an upright creature with a dominant form of visual perception of the world, characteristic of him, like any other representative of the order of primates. The hieroglyph “Tao” records the image of a person’s “visual perception of living space,” which is the main and fundamental condition for his sensory perception of the world, which precedes comprehension and understanding.

16 Xu Shen. Showen Jiezi. Beijing, 1985. P.9.

A completely adequate translation of the hieroglyph “dao” and the expression of its meaning in words and a phonetic writing system are impossible. The established translations of this hieroglyph as a philosophical concept into Russian with the words “path”, “road” only partly reflect the semantic field of its meanings. “way”, used in English literature for this purpose, although it has a wider semantic field, also does not cover all aspects of this concept. A wider, although far from complete, field of meanings for the hieroglyph “dao” is overlapped by the Russian word “khod”, which is wider than the words “path” and “road”. It is worth emphasizing that expanding the semantic field of the word “move” involves the use of different word forms of this concept. In ancient Chinese, such variability in the meanings of hieroglyphs was determined only contextually. Proposing to translate the hieroglyph “dao” into Russian with the word “move”, we proceed from the meanings of its following word forms: course, passage, transition (course of body movement - path; heavenly course, course of time; course of thought, course of reasoning; course of the world process ); sunrise, sunset; approach (approach to solving a problem - method); outcome, proceed, based on ...; intelligibly, intelligibly, make intelligible (understandable; express intelligibly, explain intelligibly; common expression: got it? (meaning - did you understand?); necessity, necessary; everyday (ordinary); resourceful, resourcefulness; petition, intercessor 17. Morpheme “move " acts as a root in the verb "to walk", which can be directly correlated with the semantics of the hieroglyph "sin". At the same time, the phrase "movement of the stars", as related to the year, the annual cycle and, accordingly, the "passage of time", gives grounds for It is impossible to translate the concept “tian dao” with this phrase. However, it is impossible to adequately express with the word “move” another anthropomorphic aspect of the semantic field of meanings of the hieroglyph “dao”. It is impossible because the hieroglyph “dao” can simultaneously take on such meanings as “to feel”, “to sense” In the Russian language, the morpheme “hod” does not take on such meanings, just as the words “path” and “road” do not take on these meanings. Thus, there are a number of other aspects in the semantic field of the hieroglyph “dao” and the concept it expresses. In particular, according to the proposed reconstruction, it clearly highlights the anthropomorphic aspects that determine the psychologization of this concept, which is clearly expressed in its lexical meanings such as “to feel, sense.” In addition, in the Chinese philosophical tradition, the character “Tao” is also interpreted in the meaning of “unity”, “single”.

17 Compare with the lexical meanings of the hieroglyph “dao” in: Large Chinese-Russian dictionary in 4 volumes. edited by I.M.Oshanina. M., Nauka, 1983. T.4. P.96.

The hieroglyph “dao”, setting the orientation towards a universal position of perception, began to be used as a sign of a universal description of reality, which is what actually happened in Chinese philosophy. This core of meanings correlates with the general structure of the position occupied by a person in the world. With what can be called human living space, which sets the conditions for its existence and is explicated in language. The hieroglyph “dao”, setting a universal position of perception, pointing simultaneously to both the “external” and the “internal”, became the central category of Chinese philosophy. In the dictionary “Shouwen Jiezi” the hieroglyph “dao” is found already in the first dictionary entry, which is devoted to the hieroglyph “i”, which takes on the dictionary meanings: “one, one, united, unity” and defined by Xu Shen: “One-Unity is the great beginning. The Tao stands in the One-Unity. Divided into Heaven and Earth. Turns into ten thousand things." 18

18 Xu Shen Zhuan, Xu Xuan Jiaoding. (Essay by Xu Shen, revised by Xu Xuan) Showen Jiezi (Explanation of Wen and Interpretation of Zi). Shanghai: Jiaoyong Chubanshe. 2004. P. 1.

The bodily position, inscribed in the hieroglyph “Tao,” sets the image of observation in motion, which is the root of the description of any interaction between the body and the world, being determined by the deep meanings of a person’s presence in the world. To understand it, it is necessary to significantly change the methodological setting, which is tantamount to the thesis put forward by M. Merleau-Ponty about the need to move the “assemblage point” to a different position. He wrote: “It is necessary that scientific thinking - the thinking of the “view from above”, the thinking of the object as such - moves to the original “is”, location, descends onto the soil of the sensually perceived and processed world as it exists in our life, for our body, - and not only for that possible body that is free to imagine as an information machine, but for the actual body that I call mine, that sentry that silently stands at the basis of my words and my actions” 19. The image of a real body as “an intertwining of vision and movement” reveals such a specific construction as “an absolute frame of reference relative to an acting person.”

19 Merleau-Ponty M. Eye and Spirit. M., 1992, p. 11.

This epistemological attitude was implemented in the Chinese cognitive tradition, an indication of which can be the existence of a specific form of knowledge “Tao”, widespread in China in ancient times and in our time. In this case, we are talking about practical methods of comprehending the “Tao”. These practices, which have a wide range of names, have applied medical as well as religious significance and are designed to help realize the understanding of the unity of the world and the body, and learn their harmonious interaction. This practice is a set of physical exercises, including stances that are widely used in therapeutic exercises of a medical and, at the same time, spiritual nature - “qigong” (“spirit training”), in the applied disciplines of “wu shu” (“martial arts”). Basic exercises, as a rule, include special stances - “posture [standing in] step” (“zhuang bu”). The practice of Zhuang Bu poses has two main starting stances: 1) legs on the same line with an even distribution of weight, 2) placing the legs in a step pose. The last stance is a literal static reproduction of the pose depicted in the hieroglyph "dao". Mastering the technique of setting a step continues with the practice of walking - that is, “tao” in dynamics. Stepping and stepping techniques are the basic discipline of many areas of Chinese traditional arts in various schools of Wushu, Taoism, Buddhism, and traditional Chinese medicine. 20

20 For example, see: Chinese qigong therapy., M.: Energoatomizdat, 1991., pp. 13.; Ma Folin., Qigong, a set of exercises to strengthen and develop the spirit and body. M., 1992. P.8-9.

Currently, the term “qigong” (“spirit training”) is widely used to denote these arts. An earlier term for them is "dao yin", where the sign "dao" is derived from the ancient full forms of the designation "dao", and the sign "yin" in its etymological meaning depicts the action of "pulling the bow string". The art of “Tao Yin” has been featured since ancient times as a therapeutic and preventive method of maintaining health and cultivating longevity. This can be judged by references, for example, in the fundamental text on traditional Chinese medicine “Huang Di Nei Jing” (“Huang Di’s Foundation on the Internal”): “[The ancestor Huang Di asked: [if in] the side of the body below you feel fullness, shortness of breath and it doesn’t stop for two or three years, how can this disease be cured? Qi-bo - The uncle-ruler of [the Zhou capital at the foot of the mountain] Qi[shan] replied: [This] disease is caused by the fact that day by day [occurs] tightness of breathing and [occurs] congestion [in the body caused by tension.] This does not interfere with the nutrition [of tissues, but] cannot be cured by cauterization and acupuncture. Congestion is treated by practicing Dao Yin and taking medicine. [Only taking] medications alone cannot cure [this disease].” 21

21 Huang Di Nei Jing. Su wen. (The basis of Huang Di is about the internal. Basic questions.) Zhuzi baijia zhi yinjia. (Medical [canonical works] of all schools of philosophers.) Zhongguo gudian jinghua wenku (Collected ancient Chinese classics). Beijing, 2001. P. 86.

The practice of "Tao Yin" is a development of ancient methods of improving the body and mind, which had everyday significance for the aristocrats of Ancient China. This can be judged on the basis of the semantics of the hieroglyph “yin”, derived from the image of a “bow with a string” and which, as already noted, served to denote the action of “pulling the bow.” Mastery in drawing a bow string, a stable stance, a correct eye and a calm state of mind are the main conditions for achieving mastery in one of the types of “six traditional arts”. As we noted earlier, according to the Zhou [Dynasty] Ceremonial, these arts are: “The first is called [the skill of performing] the five ceremonies. The second is called [skill in] six melodies. The third is called [skill in] the five [types of] archery. The fourth is called [the ability to] drive five horses [harnessed to a chariot]. The fifth is called [skill in] six [types of] writing [for] recording sayings. The sixth is called [skill in] nine calculations.” 22 Achieving special mastery in the ability to stand firmly on one's feet was also required for mastering the ancient art of combat - conducting fast, aimed archery while standing on the platform of a speeding chariot. Such combat tactics were widespread during the reign of the Shang-Yin dynasty and the first half of the reign of the Zhou dynasty. For this reason, the original life context of practicing the art of Dao Yin included not only medical, preventive and therapeutic aspects. Such skills, which were required in combat and thus determined their social, political and ritual status, were a natural part of the daily life of ancient Chinese aristocrats. As a matter of fact, the general term for designating people of the noble class in Ancient China in literal translation is “zhu hou” - this is “all archers”. The etymological meaning of the hieroglyph "hou" expressed the action of "shooting a target with a bow." Constant training in archery was an essential part of the training of a holder of aristocratic rank, which may go back even further to bowhunter cultures. In agricultural communities, archers began to appear in a new function. The bow was the most important weapon in combat until the spread, approximately in the second half of the 1st millennium BC, of crossbows, which had a radical impact on changing methods of warfare. Training in crossbow shooting was easier, which led to the mobilization of militias, along with the professional army. In ancient times, skilled archers had a high social status, which was reflected in the general designation of noble people. Thus, in the art of “Dao-yin” in the early stages of the development of Chinese society, various semantic aspects were associated that were directly related to everyday life.

22 Zhou Li (“Ceremonial of the Zhou [dynasty]”). Ser.: Zhuzi baijia zhi shi san jing. Zhonghua Gudian Jinghua Wenku (Works by authors of all [philosophical] schools. Collection of outstanding monuments of Chinese classics). Beijing, 2001. P. 29.

Subsequently, as the realities of life changed, the everyday forms of training skilled hunters and warriors were rethought, and the previous methods became sections of medical and spiritual practice, the most important element of Taoist methods of self-improvement, reflected in the text “Huang Di Nei Jing”. The oldest written example of instructions in the Dao-Yin methods was discovered in 1973 during excavations of the tomb of a representative of the family of a local ruler of the Han era near Changsha in the town of Mawangdui, where the “Dao-Yin Diagram” was discovered, which reflected 44 poses "Tao-yin". Ge Hong's (284? - 343 or 363) treatise "Baopu Tzu" says: "To stretch or bend, bend forward or backward, walk or lie, sit or stand, inhale or exhale - all this is Tao-yin." In the treatise of the court physician of the Sui era (581-618) Chao Yuanfang “Zhubing Yuanhoulun”, more than 260 treatment methods using “Dao-yin” are described. 23 “Tao-yin” became a section of a powerful tradition associated with the cult of longevity and immortality, which was included in the religious movement “Tao Jia” (“school” or literally “family of Tao”) and “Tao Jiao” (“teaching [of comprehension and achievement ] dao").

23 Feng Huaiban. Daoyin as a way of “internal nurturing” to transform the seed into qi (“leading and attracting”). // “Qigong and Life” 1998, N2.

“Dao-yin” techniques included many different exercises, including imitative ones, for example, “dancing the five animals.” This form of cognition can be correlated with the most ancient motives and practices of embodiment in the image of a game animal. The image recorded in “Tao” of “a person’s vision of his body while walking” presupposes its authentic “reading-viewing” from a special perspective - as if “a view from the inside.” This allows you to correlate the angle of this image with the angle that is given to the person by the mask. A mask is an overlay with cutouts for the eyes, so putting on a mask also means seeing the world through the eyes or slits of the mask, that is, taking a certain observation position. Similarly, in order to see the meaning of the hieroglyph “Tao”, it is necessary to understand and reproduce the observation position that is determined by the angle of the image of this pictogram. By putting on a mask, a person thereby embodied himself in its prototype and established a connection with it. These ideas were especially characteristic of totemism, where embodiment in the image of the first ancestor goes back to the motives of reincarnation in the image of animals. In the methodology expressed by the concept of “Tao,” the task is posed exactly the opposite. To understand the “Tao”, it is necessary to become a “zhen ren” - a “real person” and free yourself from other roles into which, willingly or unwillingly, a person embodies, being in the bosom of a culture that imposes on him a huge number of cultural forms of behavior.

The development of this tradition, in turn, led to the emergence of new cultural forms of behavior, embodied in all kinds of methods of self-improvement. For example, in the treatise “Baopu Tzu”, in particular, the “Book of Contemplation of the Heaven of the Greatest Purity” is mentioned, in which: “it is said that the method of prolonging life is not limited to sacrifices and service to spirits, nor the knowledge of Dao-yin gymnastics, nor the muscle flexibility. To soar upward to the immortals, you need an animated elixir. It is not easy to know, but it is truly difficult to make. If you prepare it, then you can prolong your existence. In our time, at the end of the Han Dynasty, a certain Mr. Yin from Sinye County created this elixir of the Greatest purity and gained immortality.” 24 “The Doctrine of Tao” has absorbed a large number of all kinds of rational and irrational cults, the separation and subdivision of which is not an easy task. It is also worth noting that similar traditions of “external alchemy” developed in European culture, laying the foundations of chemistry and medicinal therapy. In China, the so-called “internal alchemy” continued to play an important role, closely related to psychophysiological methods of improving the body and consciousness, which became popular in the Western tradition as modern psychology developed. In this regard, we only note that in the case of the above methods of studying the “Tao Yin” and the practical implementation of the “Tao”, the adept potentially embodies the “Tao” both figuratively and literally. From this point of view, the concept of “mastery of Tao” (“Dao Shu”), as it was called in ancient texts, had concrete methods of comprehension, and not only and not so much abstract provisions of certain doctrines.

24 Baopu Tzu. In: Religions of China. Reader. Comp. E. A. Torchinova. St. Petersburg, 2001.

These practices are also observed in other cultures. For example, in the culture of North American Indians, one type of initiation rites involved the ability to stand motionless for 24 hours on the edge of a cliff. Among African tribes, similar methods involved the ability to stand motionless on a pole. Another example of such trials for the sake of a higher goal is the asceticism of Simeon the Stylite, who built a pillar several meters high in the Syrian desert and settled on it, depriving himself of the opportunity to lie down and rest, standing day and night in an upright position. Simeon the Stylite is revered in Christianity as a saint who acquired many miraculous powers. Other Christian ascetics and stylites are also known. In the Chinese tradition, “pillar standing” is also considered an important method of human self-improvement. The importance of this method of cognition lies in knowing oneself, which is impossible otherwise, due to the natural distraction of attention to other external or internal stimuli for a person. Standing in a pillar makes it possible to try to know oneself in its entirety, including the ordinary structures of visual perception. Similarly, in the course of practical comprehension of the Tao-Yin and Qigong methods, one of the main features of these types of exercises is the requirement to achieve controlled changes in the psyche of the practitioner. The main one is the feeling of “integrity”, the feeling of experiencing one’s unity with the environment and the world. 25

25 Morozova N.V., Dernov-Pegarev V.F. "Soaring Crane" A set of exercises from the ancient Chinese health system of qigong. M.: 1993. P. 3.

The image of one’s body is a basic condition for the development of consciousness, which can be judged based on the connection between body language and thinking. 26 Knowing oneself is directly related to the possibility of knowing another (the theory of the “mind of another”). It is assumed that the development and increasing complexity of “mental structures” involved in recognizing the mental states of another person and contributing to the development of the infant’s brain is based on an even more rudimentary predisposition to create simplified images of one’s own body and establish their correspondence to images of the bodies of others. These body patterns arise very early, since already at the age of one and a half months the child shows the ability to imitate. Studies of infants with severe autism and some patients with schizophrenia have revealed that they have poor development of the ability to “attribute” (recognize the mental states of another person). A person's predisposition to make moral judgments is rooted in his ability to create mental structures involved in evaluating “himself as another.” The ability to “put oneself in the place of another,” to recognize possible differences or, on the contrary, identity between one’s own state and the state of another, can also be considered in the sense of the ability to perceive another as a “sign” and interpret its “meanings.” The ability to evaluate “oneself as another” can also be considered in this aspect. In this case, the “sign” is the person himself for himself, which is most directly reflected in the form of the hieroglyph “Tao”, which records how a person visually perceives himself. The above can also serve as an explanation for the appearance of such lexical meanings of the hieroglyph “dao” as: “high integrity; perfect behavior; high ethical standards; high morals (which a person should follow).” The expression “having the Tao” means “endowed with high morality, highly moral [person].” 27

26 For more details see: Martynenko N.P. Culture as the transformation of signs - wenhua. T. 1-2. M.: Publishing house "SP Mysl". 2006. Volume 1. P.38-40.

27 Ibid.

In Chinese culture, the requirement to follow the “Tao” is dominant, which presupposes likeness to the world and correlation with the “Tian Dao” - the “celestial course”, manifested in the alternation of days and nights, years and winters, the rotation of the constellations of the firmament above a person’s head throughout the year, sunrises and sunsets. This is also expressed in the Russian language, where the sun also “rises” and “sets,” which shows the deep unity of the ways of describing the world in different languages. The expression “tian dao” can literally be translated as “heavenly passage”, in the sense of “course of time”. The concept of “tian dao” indicates a visual image that is directly related to the Russian concept of “time”, but not in its modern abstract understanding, but in its etymological sense, derived from the verb “to twirl”. The complex of ideas about “tian dao” is based on the fact that for an earthly observer the sky, resembling a dome, is mobile, and the earth is motionless. Changes in the celestial sphere are directly related to temporary changes. The stars describe a circle around the celestial axis throughout the year. The movement of the sun changes throughout the day and also throughout the year. Movement and changes of the lunar disk during the month. These systems of representations are based on visual-spatial images. These images are set by the living space of a person, which, on the one hand, is determined by human nature and his objective and practical activities, and on the other, determined by the world around him, in the process of mastering which these images are updated, which have become the most important categories of Chinese religion, philosophy, and science.

Understanding the hieroglyph “dao” in the meaning of “That (one) that (who) walks” provides the basis for its comparison with the concept of “Wu Xing” - “Five Steps”, which is the name of the ancient teaching - a universal system of classification of phenomena. The relationship between the concepts of “dao” and “wu xing” can be judged on the basis of the intersection of their semantic fields, which is clearly seen when comparing the derivatives of the ancient forms of the hieroglyph “dao” with the hieroglyph “xing”. The concept of “Tao” in this context can be interpreted as an internal image of walking “Xing”, expressed in the form of five steps - phases of development and existence of the unity of the world or “Tao - which walks”. A literal understanding of these images may seem banal. The depth of the system of thought expressed in them and their philosophical understanding can only be understood within the framework of the entire system of Chinese culture, in which these, at first glance, simple images are filled with deep philosophical content. As philosophical concepts expressed in symbols, they can only be understood systematically, within the framework of the structure of relationships and through the prism of relationships that have developed in Chinese culture over thousands of years. When interpreting the signs that express them, not only their lexical meanings are important, but also the semantics of the drawings underlying these hieroglyphs. It is in the semantics of these drawings that the basic semantic structures expressed in ancient texts are reflected.

Therefore, in the works of ancient philosophers there are often examples of explaining the meaning of terms through their etymon. This approach, supplemented by the study of the cultural, historical and linguistic context, can allow us to reconstruct the history of the development of concepts that arose in the process of understanding the semantics of ancient drawings - prototypes of hieroglyphic signs that were used in Chinese culture for thousands of years and were filled with a huge number of semantic connections. The fundamental categories of Chinese philosophy and culture carry an anthropomorphic image. Moreover, anthropomorphic in the literal sense of the word (from the Greek ἄνθρωπος - man and μορφή - appearance, image, appearance 28). Anthropomorphism refers to the assimilation of objects in the surrounding world to humans, endowing them with human properties. Anthropomorphism arises as the initial form of worldview and is expressed not only in endowing objects of the surrounding world with characteristics inherent in the human psyche, but also in attributing to them the ability to act, abilities and actions similar to those of humans 29 . It is generally accepted that this form of anthropomorphism dominated the early stages of the development of society, and is still present in a number of religious doctrines. For example, the above myths about the First Man are archaic classifications and descriptions of the world in the image and likeness of the human body, which acts as a sign of the world. Echoes of this type of understanding of the world are presented in large numbers in different languages of the world, in art and in poetry, where the anthropomorphism of images serves for emotional expressiveness. With any methods of describing the world, the person himself always remained in the field of view, his central role was how he saw and experienced himself. Therefore, the image of a person’s body is a central element of perception of the world. Language clearly manifests the perception of the world on the principle of comparing it with already known objects, for example, with the human body and its parts, or vice versa. The mixture of physiological, mental and material-physical concepts and categories is a distinctive feature of any ancient culture and philosophical system of thinking. This feature continues, in one form or another, to exist in any language system. We can still find a huge number of examples of the interpenetration of the human and natural worlds in the lexical expressions of any language. Ancient Chinese and Chinese languages are no exception in this regard. These linguistic concepts were reflected in the ancient forms of hieroglyphic characters, which became symbols of the most important philosophical and mythological concepts of Chinese civilization.

28 Weisman A.D. Greek-Russian dictionary. M., 1991. P. 827.

29 Philosophical encyclopedic dictionary. M.: “Soviet Encyclopedia”. 1983. P.30.

Martynenko N.P.

Text kindly provided by the author

Taoism is a bizarre phenomenon, different, like a patchwork quilt. This is not a religion, not a doctrine, not a philosophy, not even a conglomerate of schools. Rather, it is a special mood of consciousness inherent in the Chinese ethnic group. If Confucianism is how the bearers of this tradition think about themselves, then Taoism is what they really are, and these parts of the “I” - the real “I” and the ideal “I” - are indissoluble and are obliged to live together .

Taoism is a somewhat arbitrary term, as the Confucians called all those people - and there were many of them - who “talked about Tao.” They could perform different rituals and adhere to different types of practices, be healers, healers, magicians, and wandering warriors.

Taoism left behind a considerable number of symbols that are associated with the most ancient, most archaic ideas about spirits, “floors” of Heaven, travel to the afterlife and communication with ancestors. Taoism still widely uses a kind of “secret writing”, so reminiscent of the magical signs of shamans - a system of slightly modified hieroglyphs, which, when written, for example, on the wall of a house or on colored paper, influence the world of spirits in a certain way.

There can be no holiness and “trembling of the soul” before meeting the divine in Taoism, because Tao does not require personal experience. What is more important here is the practical aspect of self-development, numerous methods of “internal art” (neigong), sexual practices of nurturing qi energy and jing seed, leading to the birth of an “immortal embryo” in the body.

Once, the famous calligrapher and follower of Taoism Wang Xizhi, who loved to eat geese, asked for one of them from the famous Taoist who raised these birds. The Taoist refused, Wang Xizhi made his request several more times, but the answer was still negative. Finally, the Taoist took pity on the calligrapher and said that he would give up the goose if Wang Xizhi rewrote the Tao Te Ching with his own hand. He did so, and a strange exchange of the sacred text for the unsacred goose took place. This story is usually cited as an example of the popularity of Taoist teaching, but it is more reasonable to see in it devotion to the goose - that is, an absolute lack of distinction between the sacred and the profane.

In its pure form, Taoism was never the prevailing teaching in China and, in essence, occupied a rather modest place. The idea that most Chinese perform Taoist rituals is due to the fact that Taoism is often confused with local cults, prayers to the spirits of ancestors, that is, with everything that really is the core of the spiritual life of both ancient and modern Chinese. Today, dozens of Chinese come to Taoist monasteries every day, but not at all in order to “profess the Taoist religion,” but then to worship the spirits of their ancestors or to cleanse themselves of harmful spirits. Taoist, as well as Buddhist monks, fulfilling the role of ancient mediums and magicians, serve the population by performing wedding ceremonies, rituals associated with funeral services for the dead or the birth of children.