During the 50s and 60s of the 17th century, the Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Nikon and Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, actively implemented church reform aimed at introducing changes to liturgical books and rituals in order to bring them into line with Greek models. Despite its expediency, the reform caused protest in a significant part of society and caused a church schism, the consequences of which are still felt today. One of the manifestations of popular disobedience was the uprising of the monks of the monastery, which went down in history as the Great Solovetsky Sitting.

Monks who became warriors

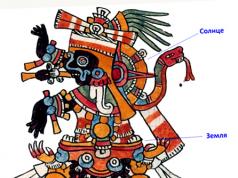

In the first half of the 15th century, on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, a monastery was founded by Saints Savvaty and Zosima (their icon opens the article), which over time became not only a major spiritual center of the North of Russia, but also a powerful outpost on the path of Swedish expansion. In view of this, measures were taken to strengthen it and create conditions that allowed the defenders to withstand a long siege.

All the inhabitants of the monastery had a certain skill in conducting military operations, in which each of them, on alert, took a certain, designated place on the walls of the fortress and at the tower loopholes. In addition, a large supply of grain and various pickles was stored in the basements of the monastery, designed in case the besieged lost contact with the outside world. This made it possible for the participants of the Solovetsky seat, who numbered 425 people, to resist the tsarist troops, which significantly outnumbered them, for 8 years (1668 ─ 1676).

Rebellious monks

The beginning of the conflict, which later resulted in an armed confrontation, dates back to 1657, when new liturgical books sent from Moscow were delivered to the monastery. Despite the patriarch’s command to immediately put them into use, the council of cathedral elders decided to consider the new books heretical, seal them, remove them out of sight, and continue to pray as it had been customary since ancient times. Due to the distance from the capital and the lack of means of communication in those days, the monks got away with such insolence for quite a long time.

An important event that determined the inevitability of the Solovetsky seat in the future was the Great Moscow Council of 1667, at which everyone who did not want to accept the reform of Patriarch Nikon and was declared schismatics was anathematized, that is, excommunicated. Among them were the obstinate monks from the White Sea islands.

The beginning of armed confrontation

At the same time, to admonish them and restore order, a new abbot, Archimandrite Joseph, loyal to the patriarch and sovereign, arrived at the Solovetsky Monastery. However, by the decision of the general meeting of the brethren, he was not only not allowed to rule, but also very unceremoniously expelled from the monastery. The authorities perceived the refusal to accept the reform and then the expulsion of the patriarch's protege as an open rebellion and hastened to take appropriate measures.

By order of the tsar, a streltsy army was sent to suppress the uprising under the command of governor Ignatius Volokhov. It landed on the islands on June 22, 1668. The Solovetsky sitting began with an attempt by the sovereign's servants to enter the territory of the monastery and decisive resistance from the monks. Convinced of the impossibility of a quick victory, the archers organized a siege of the rebellious monastery, which, as mentioned above, was a well-defended fortress built according to all the rules of fortification.

Initial stage of the conflict

The Solovetsky sitting, which lasted almost 8 years, in the first years was only occasionally marked by active hostilities, since the government still hoped to resolve the conflict peacefully, or at least with the least bloodshed. In the summer months, the archers landed on the islands and, without trying to penetrate inside the monastery, they only tried to block it from the outside world and interrupt the connection of the inhabitants with the mainland. With the onset of winter, they left their positions and most of them went home.

Due to the fact that during the winter months the defenders of the monastery had no isolation from the outside world, their ranks were regularly replenished by fugitive peasants and surviving participants in the uprising led by Stepan Razin. Both of them openly sympathized with the anti-government actions of the monks and willingly joined them.

Aggravation of the situation around the monastery

In 1673, a significant turning point occurred during the Solovetsky sitting. Its date is generally considered to be September 15 - the day when the royal governor Ivan Meshcherinov, a decisive and merciless man, arrived on the islands, replacing the former commander K. A. Ivlev at the head of the increased Streltsy army by that time.

According to his authority, the governor began shelling the fortress walls from guns, which had never been attempted before. At the same time, he handed over the highest letter to the defenders of the monastery, in which, on behalf of the king, forgiveness was guaranteed to all who would stop resistance and voluntarily lay down their arms.

A king deprived of prayerful remembrance

The cold weather that soon set in forced the besiegers, as in previous times, to leave the island, but this time they did not go home, and during the winter their number doubled due to the arrival of reinforcements. At the same time, a significant amount of guns and ammunition was delivered to the Sumy fort, where the archers spent the winter.

At the same time, as historical documents testify, the attitude of the besieged monks to the personality of the king himself finally changed. If before they prayed in the established order for the health of Emperor Alexei Mikhailovich, now they called him nothing more than Herod. Both the leaders of the uprising and all ordinary participants in the Solovetsky sitting refused to commemorate the ruler at the liturgy. Under what king could this happen in Orthodox Rus'!

The beginning of decisive action

The Solovetsky seat entered its new phase in the summer of 1675, when Voivode Meshcherinov ordered to surround the monastery with 13 fortified earthen batteries and begin digging under the towers. In those days, during several attempts to storm the impregnable fortress, both sides suffered significant losses, but in August another 800 Kholmogory archers arrived to help the tsarist troops, and the ranks of the defenders have not been replenished since then.

With the onset of winter, the governor made an unprecedented decision at that time - not to leave the walls of the monastery, but to remain in position even in the most severe frosts. By this, he completely excluded the possibility of the defenders replenishing their food supplies. That year the fighting was fought with particular ferocity. The monks repeatedly made desperate forays, which claimed dozens of lives on both sides, and filled up the dug tunnels with frozen earth.

The sad outcome of the Solovetsky sitting

The reason why the fortress, held by the defenders for almost 8 years, fell is offensively simple and banal. Among hundreds of brave souls, there was a traitor who, in January 1676, fled from the monastery and, coming to Meshcherinov, showed him a secret passage leading from the outside through the monastery wall and only for external camouflage, blocked with a thin layer of bricks.

One of the next nights, a small detachment of archers sent by the governor quietly dismantled the brickwork in the indicated place and, having entered the territory of the monastery, opened its main gate, into which the main forces of the attackers immediately poured. The defenders of the fortress were taken by surprise and were unable to provide any serious resistance. Those of them who managed to run out to meet the archers with weapons in their hands were killed in a short and unequal battle.

Fulfilling the sovereign's command, governor Meshcherinov mercilessly dealt with those rebels who, by the will of fate, turned out to be his captives. The rector of the monastery, Archimandrite Nikanor, his cell attendant Sashko and 28 other most active inspirers of the uprising, after a short trial, were executed with particular cruelty. The governor sent the rest of the monks and other inhabitants of the monastery to eternal imprisonment in Pustozersky and Kola prisons.

Defenders of the monastery who became Old Believer saints

All the events described above then received wide coverage in Old Believer literature. Among the most famous works of this direction are the works of a prominent figure in the religious schism, A. Denisov. Secretly published in the 18th century, they quickly gained popularity among Old Believers of various persuasions.

At the end of the same 18th century, among Orthodox believers who broke away from the official church, it became a tradition annually on January 29 (February 11) to celebrate the memory of the holy martyrs and confessors who suffered in the Solovetsky Monastery for “ancient piety.” On this day, prayers are heard from the pulpits of all Old Believer churches addressed to the saints of God who have won the crown of holiness on the snow-covered islands of the White Sea.

The Solovetsky uprising of 1668-1676 became the personification of the struggle of the clergy against Nikon’s reforms. This uprising is often called a “sitting”, since the monks held the Solovetsky Monastery, asking the tsar to come to his senses and cancel the reforms. This page of Russian history has been little studied, since there are practically no sources, but there is enough information to form an objective picture of what was happening in those days. After all, the uprising in the Solovetsky Monastery of the 17th century is unique. This is one of the few cases where the uprising was not due to social or economic reasons, but to religious ones.

Causes of the uprising

Nikon's reforms radically changed the Orthodox Church: rituals, books, and icons were changed. All this caused discontent among the clergy, who later began to be called “Old Believers.” This was the reason for the Solovetsky uprising. However, this did not happen immediately. Since the mid-50s, the monks expressed dissatisfaction and sent petitions to the king with requests to cancel the reforms. The general chronology of the prerequisites and reasons for “sitting” is as follows:

- 1657 - updated church books are published in Moscow for everyone. These books arrived at the Solovetsky Monastery in the same year, but they were sealed in the treasury chamber. The monks refused to conduct church services according to the new rules and texts.

- 1666-1667 - 5 petitions were sent from Solovki to the Tsar. The monks asked to preserve the old books and rituals. They emphasized that they remained faithful to Russia, but asked not to change religion.

- beginning of 1667 - The Great Moscow Cathedral anathematized the Old Believers.

- July 23, 1667 - by royal decree, Solovki receives a new abbot - Joseph. This was a person close to the Tsar and Nikon, which means he shared the views of the reform. The monks did not accept the new man. Joseph was expelled, and the Old Believer Nikanor was installed in his place.

The last event in many ways became the pretext for the start of the siege of the monastery. The king took Joseph's expulsion as a rebellion and sent an army.

From the era of Peter 1 to the present day, the Solovetsky “sitting” is also attributed to economic reasons. In particular, such authors as Syrtsov I.Ya., Savich A.A., Barsukov N.A. and others claim that Nikon cut funding for the monastery and it was for this reason that the monks began the uprising. There is no documentary evidence of this, so such hypotheses cannot be taken seriously. The point is that such historians are trying to portray the monks of the Solovetsky Monastery as “grabbers” who cared only about money. At the same time, attention is diverted in every possible way from the simple fact that the uprising became possible only because of Nikon’s religious reforms. Tsarist historians took Nikon’s side, which means everyone who disagreed was accused of all sins.

Why was the monastery able to resist the army for 8 years?

The Solovetsky Monastery was an important outpost of Russia in the war with Sweden of 1656-1658. The island on which the monastery is located is close to the borders of the state, so a fortress was built there and supplies of food and water were created. The fortress was strengthened in such a way that it could withstand any siege from Sweden. According to data for 1657, 425 people lived in the monastery.

Progress of the uprising

May 3, 1668 Alexey Mikhailovich sends archers to pacify Solovki. The army was led by solicitor Ignatius Volokhov. He had 112 people under his command. When the army reached Solovki, on June 22, the monks closed the gates. The "sitting" began.

The plan of the royal army was to besiege the fortress so that the defenders would surrender themselves. Volokhov could not storm the Solovetsky Monastery. The fortress was well fortified and 112 people were not enough to conquer it. Hence the sluggish events at the beginning of the uprising. The monks were holed up in the fortress, the tsarist army tried to organize a siege so that famine would set in the fortress. There was a large supply of food in Solovki and the local population actively helped the monks. This “sluggish” siege lasted 4 years. In 1772, Volokhov was replaced by governor Ievlev, who had 730 archers under his command. Ievlev tried to tighten the blockade of the fortress, but did not achieve any results.

In 1673, the Tsar made a decision to take the Solovetsky Monastery by storm. For this:

- Ivan Meshcherinov was appointed commander, who arrived at the fortress across the White Sea in the early autumn of 1673.

- During the assault, it was allowed to use any military techniques, as against a foreign enemy.

- Each rebel was guaranteed a pardon in case of voluntary surrender.

The siege continued for a year, but there were no serious attempts at assault. At the end of September 1674 Frosts began early and Meshcherinov took the army to the Sumy prison for the winter. During the wintering period, the number of archers doubled. Now about 1.5 thousand people took part in the assault.

September 16, 1674 One of the most important events of the uprising happened in the Solovetsky Monastery - the rebels held a Council to stop the pilgrimage for Tsar Herod. There was no unanimous decision and the Council divided the monks. As a result, everyone who decided to continue their prayers for the Tsar was expelled from Solovki. It should be added that the first “Black Council” in the Solovetsky Monastery took place on September 28, 1673. Then it was also established that Alexey Mikhailovich was mistaken, but prayers would help clear his mind.

By May 1675, 13 towns (embankments from which the fortress could be fired upon) had been established around the Solovetsky Monastery. The assaults began, without success. From July to October, 32 of those born were killed and another 80 were injured. There is no data on losses in the tsarist army.

On January 2, 1676, a new assault began, during which 36 archers were killed. This assault showed Meshcherinov that it was impossible to capture Solovki - the fortress was so well fortified. Defectors played a decisive role in subsequent events. Theoktist, who was expelled from the citadel for his desire to continue praying for Tsar Herod, on January 18 told Meshcherinov that the Bloya Tower had a weak point. The tower had a drying window, which was blocked with bricks. If you break a brick wall, you can easily get inside the fortress. The assault began on February 1, 1676. 50 archers entered the fortress at night, opened the gates and the monastery was captured.

Consequences and outcome

A preliminary investigation of the monks was carried out right in the monastery. Nikanor and Sashko were recognized as the main instigators of the uprising and were executed. The rest of the rebels were sent to various prisons. The main result of the Solovetsky uprising is that the stratification in the church took root, and from that time on the Old Believers officially appeared. Today it is generally accepted that the Old Believers are almost pagans. In fact, these are the people who opposed Nikon’s reforms.

Solovetsky uprising 1668-1676- an uprising of the monks of the Solovetsky Monastery against the church reforms of Patriarch Nikon. Due to the monastery’s refusal to accept innovations, the government took strict measures in 1667 and ordered the confiscation of all estates and property of the monastery. A year later, the royal regiments arrived in Solovki and began to besiege the monastery.

Story

Official historians of the Russian church tried to present the Solovetsky uprising of 1668 - 1676 as an uprising of ignorant supporters of the old faith against Nikon's progressive reforms. The progressiveness of Nikon's reforms is very relative, as is the ignorance of the Old Believers in the 17th century. Democratic and exploited sections of Russian society joined the opposition to the official church. The Solovetsky uprising broke out on the crest of popular uprisings of the 17th century. In the summer of 1648, an uprising occurred in Moscow, then in Solvychegodsk, Veliky Ustyug, Kozlov, Voronezh, and Kursk. In 1650, uprisings broke out in Pskov and Novgorod. In the early 60s there was unrest over new copper money. These unrests were called “copper riots.” The Solovetsky uprising of 1668 - 1676 was the end of all these unrest and the Peasant War led by Stepan Razin, but discontent in the monastery appeared much earlier. Apparently, already in 1646, dissatisfaction with the government was felt in the monastery and its possessions. On June 16, 1646, Abbot Ilya wrote to bring lay people of various ranks, archers and peasants in monastic estates to the kiss of the cross. The oath form was soon sent from Moscow. The monastic people were obliged to serve the sovereign faithfully, to want his good without any cunning, to report any crowd or conspiracy, to carry out military work without any treason, not to join traitors, not to do anything arbitrarily, in a crowd or conspiracy, etc. From this it is clear that the danger of "ospreys", conspiracies and betrayals was real.

The gradually accumulating dissatisfaction with Patriarch Nikon resulted in 1657 in a decisive refusal of the monastery, headed by its then Archimandrite Ilya, to accept the newly printed liturgical books. The monastery's disobedience took on various forms in subsequent years and was largely determined by pressure from below from the laity (primarily workers) and ordinary monks living in the monastery. The following years were filled with numerous events, during which the monastery, torn by internal contradictions, as a whole still refused to submit not only to the ecclesiastical authority of the patriarch, but also to the secular authority of the tsar.

In 1668, an armed struggle between the monastery and the tsarist troops began. The monastery was besieged and remained under siege for eight years. There were up to seven hundred to seven hundred and fifty of its defenders in the monastery.

The rebels were joined by former Razinites and various other dissatisfied people. Characteristic in this regard are the testimony of Elder Prokhor: “The brethren in the monastery totaled three hundred people, and the Beltsi (that is, not monks, secular ones. - D.L.) more than four hundred people, locked themselves in the monastery and sat down to die, but no one which the images do not want. And they began to stand for theft and for Kapitonism (the first Old Believers-bespopovtsy, supporters of Elder Kapiton. - D.L.), and not for the faith. And during the Razinov era, many capitons, monks and Beltsy from the lower towns came to the monastery, and they excommunicated their thieves from the church and from their spiritual fathers. Yes, in their monastery they gathered Moscow fugitive archers and Don Cossacks and boyar fugitive slaves and various state foreigners... and the root of all evil gathered here in the monastery.”

The monastery's reserves would have been enough for a much longer period, but the betrayal of the monk Theoktistus, who gave the tsar's governor Meshcherinov a secret passage through the drying hole, put an end to the armed struggle. The reprisal against the rebels was extremely harsh. Apparently, during the last year of the siege, at least four hundred people remained in the monastery. Only fourteen were left alive. According to the traitor Theoktist, Meshcherinov “hanged some thieves, and froze many, dragging them behind the monastery to the lip (that is, to the bay). Those executed were buried on the island “Babya Luda” at the entrance to Blagopoluchiya Bay. The corpses were not buried: they were thrown with stones.

No matter how much the official historians of the monastery tried to present the matter as if Solovki, after the suppression of the uprising, did not lose their moral authority in the North, this was not the case. The role of Solovki in the cultural life of the North sharply declined. Solovki found itself surrounded by Old Believer settlements, for which the monastery remained only a holy memory. Andrei Denisov, in his “History of the Fathers and Sufferers of Solovetsky,” described the “languid ruin” of the Solovetsky Monastery, the martyrdom of the Solovetsky sufferers, and his work, having been sold in hundreds of copies and printed copies, became one of the most favorite readings among the Old Believers. Solovki are a thing of the past.

At the same time, the Solovetsky uprising was of great importance in strengthening the Old Believers in northern Russia. Despite the fact that the uprising was brutally suppressed, or perhaps precisely because of this, it served to strengthen the moral authority of the old faith among the surrounding population, accustomed to seeing the Solovetsky Monastery as one of the main shrines of Orthodoxy. Attempts to use the former authority of the Solovetsky Monastery in the fight against the Old Believers after the suppression of the uprising led to nothing. The uprising showed that, ideologically and socially, the monastery was not a cohesive group. The monastery of those centuries cannot be considered as a kind of homogeneous organization acting in only one, official direction. It was a social organism in which the forces of various class interests were at work. Due to the complexity and development of economic and cultural life, various contradictions were most clearly reflected here, and new social and ideological phenomena arose. The monastery did not live a slow and lazy life, as it seemed to many, but experienced turbulent events and actively intervened in the state life and social processes of the Russian North. Resistance to Nikon's reforms was only a pretext for an uprising, behind which there were more complex reasons. Dissatisfied people joined the old faith, since the Old Believers were an anti-government phenomenon and directed against the dominant church.

Literature

- Borisov A. M. Economy of the Solovetsky Monastery and the struggle of peasants with northern monasteries in the 16th - 17th centuries.

- Barsukov I. A. Solovetsky uprising (1668 - 1676). Petrozavodsk, 1954; Syrtsov I. Ya. Indignation of the Solovetsky Old Believers monks of the 17th century. Kostroma, 1889.

- Barsov E. New materials for the history of Russian Old Believers of the 17th - 18th centuries. 1890, p. 122; Readings of IOIiDR, book. 4, 1883, Mixture; Acts related to the history of the Solovetsky rebellion. Publication by E. Barsov, doc. 26, p. 78 - 80.

Solovetsky Monastery and the defense of the White Sea region in the 16th–19th centuries Frumenkov Georgy Georgievich

§ 2. Monastic army in the 17th century. Militarization of the brethren Solovetsky uprising 1668–1676

§ 2. Monastic army in the 17th century. Militarization of the brethren

Solovetsky uprising 1668–1676

Since the time of the Troubles, the number of monastic troops has increased significantly. By the 20s of the 17th century, there were 1,040 people “under arms” in Pomerania. All of them were supported by the monastery and were distributed among three main points: Solovki, Suma, Kem. The abbot was considered the supreme commander, but the “coastal” archers were under the direct command of a governor sent from the capital, who lived in the Sumy fort. Together with the Solovetsky abbot and under his leadership, he was supposed to protect the North. Such “dual power” did not suit the abbot, who wanted to be the sole military commander of the region. His claims were well founded. By this time, the “meek” Chernorisians had become so carried away by military affairs and had mastered it to such an extent that they considered it possible and profitable to remain without military specialists. They no longer needed their help, and did not want to endure embarrassment. The king understood the wishes of his pilgrims and respected their request. According to the proposal of the abbot, who referred to the monastic poverty, in 1637 the Solovetsky-Sumy voivodeship was liquidated. The last governor, Timofey Kropivin, handed over the city and prison keys to the abbot and left for Moscow forever. The defense of Pomerania and the monastery began to be in charge of the Solovetsky abbot with the cellarer and brethren. From that time on, the abbot in the full sense of the word became the northern governor, the head of the defense of the entire Pomeranian region.

The protection of the vast possessions of the monastery required a larger armed force than that which was at the disposal of the abbot. One thousand archers were not enough. Additional detachments of warriors were needed, and this required large expenditures. The monks found another way out. In order not to spend money on hiring new batches of archers, they themselves began to study the art of war. In 1657, the entire brethren (425 people) were called to arms and certified in a military manner. Each monk received a “rank”: some became centurions, others foreman, others - ordinary gunners and archers. In peacetime, the “monk squad” was listed in the reserves. In the event of an enemy attack, the warrior monks had to take places at combat posts, and each of them knew where he would have to stand and what to do: “In the holy gates to the Transfiguration Tower, tell the cellarer, Elder Nikita, and with him:

1. Gunner Elder Jonah the Carpenter at a large, toasty copper cannon, and with him 6 people (names follow) to turn the worldly people;

2. Gunner Elder Hilarion, a sailor, at the copper shotgun, and with him to turn the worldly people - 6 hired men;

3. Pushkar Pakhomiy...", etc.

The militarization of the monastery made the Solovetsky fortress invulnerable to external enemies and, oddly enough, caused a lot of trouble for the government.

The end of the 17th century in the life of the Solovetsky Monastery was marked by the anti-government uprising of 1668–1676. We will not examine in detail the “rebellion in the monastery”, since this is beyond the scope of our topic, especially since such work has already been done. Peculiar, contradictory, complex both in the composition of the participants and in their attitude to the means of struggle, the Solovetsky uprising has always attracted the attention of scientists. Pre-revolutionary historians and Marxist historians approach the study of the uprising in the Solovetsky Monastery from different methodological positions and naturally come to diametrically opposed conclusions.

The bourgeois historiography of the issue, represented mainly by historians of the church and the schism, does not see in the Solovetsky uprising anything other than religious unrest and the “sitting” of the monks, namely the “sitting” and only the monks (emphasis mine - G.F.), for the old faith , in which “all the noble kings and great princes and our fathers died, and the venerable fathers Zosima, and Savvatius, and Herman, and Metropolitan Philip and all the holy fathers pleased God.” Soviet historians consider the Solovetsky uprising, especially at its final stage, as an open class battle and a direct continuation of the peasant war led by S. T. Razin, and see in it the last outbreak of the peasant war of 1667–1671.

The Solovetsky uprising was preceded by 20 years of passive resistance, peaceful opposition of the aristocratic elite of the monastery (cathedral elders) against Nikon and his church reform, into which the ordinary brethren (black elders) were drawn in from the late 50s. In the summer of 1668, an open armed uprising of the masses against feudalism, church and government authorities began in the Solovetsky Monastery. The period of armed struggle, which lasted as long as 8 years, can be divided into two stages. The first lasted until 1671. This was the time of the armed struggle of the Solovki residents under the slogan “for the old faith”, the time of the final demarcation of supporters and opponents of armed methods of action. At the second stage (1671–1676), participants in the peasant war of S. T. Razin came to lead the movement. Under their influence, the insurgent masses are breaking with religious slogans.

The main driving force behind the Solovetsky uprising at both stages of the armed struggle was not the monks with their conservative ideology, but the peasants and Balti people - temporary residents of the island who did not have a monastic rank. Among the Balti people there was a privileged group, adjoining the brethren and the cathedral elite. These are the servants of the archimandrite and the cathedral elders (servants) and the lower clergy: sextons, sextons, clergy members (servants). The bulk of the Beltsy were laborers and working people who served the internal monastery and patrimonial farms and were exploited by the spiritual feudal lord. Among the workers who worked “for hire” and “by promise”, that is, for free, who vowed to “atone for their sins with God-pleasing labor and earn forgiveness,” there were many “walking”, runaway people: peasants, townspeople, archers, Cossacks, and Yaryzheks. They formed the main core of the rebels.

Exiles and disgraced people, of whom there were up to 40 people on the island, turned out to be good “combustible material.”

In addition to the working people, but under their influence and pressure, part of the ordinary brethren joined the uprising. This should not be surprising, since the black elders by their origin were “all peasant children” or came from the suburbs. However, as the uprising deepened, the monks, frightened by the determination of the people, broke with the uprising.

An important reserve of the rebellious monastic masses were the Pomeranian peasantry, workers in the salt fields, mica and other industries, who came under the protection of the walls of the Solovetsky Kremlin.

According to the voivod's letters to the tsar, there were more than 700 people in the besieged monastery, including over 400 strong supporters of the fight against the government using the peasant war method.

The rebels had at their disposal 90 cannons placed on towers and fences, 900 pounds of gunpowder, a large number of handguns and bladed weapons, as well as protective equipment.

Documentary materials indicate that the uprising in the Solovetsky Monastery began as a religious, schismatic movement. At the first stage, both laity and monks came out under the banner of defending the “old faith” against Nikon’s innovations. The struggle of the exploited masses against the government and the patriarchate, like many popular uprisings of the Middle Ages, took on a religious ideological shell, although in fact, under the slogan of defending the “old faith,” “true Orthodoxy,” etc., the democratic strata of the population fought against the state and monastic feudalism. serfdom oppression. V. I. Lenin drew attention to this feature of the revolutionary actions of the peasantry suppressed by darkness. He wrote that “...the appearance of political protest under a religious guise is a phenomenon characteristic of all peoples, at a certain stage of their development, and not of Russia alone.”

In 1668, for refusing to accept the “newly corrected liturgical books” and for opposing church reform, the tsar ordered the monastery to besieged. An armed struggle between the Solovki residents and government troops began. The beginning of the Solovetsky uprising coincided with the peasant war flaring up in the Volga region and southern Russia under the leadership of S. T. Razin.

The government, not without reason, feared that its actions would stir up all of Pomorie and turn the region into a continuous area of popular uprising. Therefore, in the first years the siege of the rebellious monastery was carried out sluggishly and intermittently. In the summer months, the tsarist troops (streltsy) landed on the Solovetsky Islands, tried to block them and interrupt the connection between the monastery and the mainland, and for the winter they went ashore to the Sumsky fort, and the Dvina and Kholmogory streltsy, who were part of the government army, went home during this time .

The transition to open hostilities extremely aggravated social contradictions in the rebel camp and accelerated the disengagement of the fighting forces. It was finally completed under the influence of the Razins, who began to arrive at the monastery in the autumn of 1671, that is, after the defeat of the peasant war. People “from Razin’s regiment” who joined the rebellious mass took the initiative in the defense of the monastery into their own hands and intensified the Solovetsky uprising. The Razinites and workers become the actual owners of the monastery and force the monks, for whom they themselves previously worked, to “work.”

From the voivod's letters we learn that the enemies of the tsar and the clergy, “outright thieves and factory owners and rebels... traitors to the great sovereign,” the fugitive boyar slave Isachko Voronin and the Kemlyan (from the Kem volost) Samko Vasiliev, came to lead the uprising. The Razin atamans F. Kozhevnikov and I. Sarafanov also belonged to the command staff of the uprising. The second stage of the Solovetsky uprising begins, in which religious issues receded into the background and the idea of fighting “for the old faith” ceased to be the banner of the movement. Having broken with the reactionary theological ideology of the monks and freed itself from the Old Believer demands, the uprising took on a pronounced anti-feudal, anti-government character.

In the “questioning speeches” of people from the monastery, it is reported that the leaders of the uprising and many of its participants “do not go to God’s church, and do not come to confession to the spiritual fathers, and the priests are cursed and called heretics and apostates.” Those who reproached them for the fall were answered: “We can live without priests.” The newly corrected liturgical books were burned, torn, and drowned in the sea. The rebels “gave up” their pilgrimage for the great sovereign and his family and did not want to hear any more about it, and some of the rebels spoke about the king “such words that it’s scary not only to write, but even to think.”

Such actions finally scared the monks away from the uprising. Not to mention the opposition leadership of the monastery, even the rank and file of the brethren breaks with the movement, they themselves resolutely oppose the armed method of struggle and try to distract the people from this, taking the path of treason and organizing conspiracies against the uprising and its leaders. Only a fanatical supporter of the “old faith,” Archimandrite Nikanor, who was exiled to Solovki with a group of like-minded people until the end of the uprising, hoped to force the tsar to cancel Nikon’s reform with the help of weapons. According to the black priest Pavel, Nikanor constantly walked around the towers, burned incense and sprinkled water on the cannons and called them “mother galanochkas, we have hope in you,” and ordered to shoot at the governor and the military men. Nicanor was a fellow traveler of the people; the disgraced archimandrite and the rebel working people used the same means of struggle to achieve different goals.

The people's leaders decisively dealt with reactionary monks who were engaged in subversive activities; They put some in prison, others were expelled from the monastery. Several parties of opponents of the armed uprising - elders and monks - were expelled from the walls of the fortress.

Since the beginning of the 70s, the Solovetsky uprising, like a peasant war under the leadership of S.T. Razin, becomes an expression of the spontaneous indignation of the oppressed classes, the spontaneous protest of the peasantry against feudal-serf exploitation.

The population of Pomerania expressed sympathy for the rebellious monastery and provided it with constant support with people and food. The black priest Mitrofan, who fled from the monastery in 1675, said in a “questioning speech” that during the siege, many people came to the monastery “with fish and food supplies from the shore.” The royal letters, which threatened severe punishment for those who delivered food to the monastery, had no effect on the Pomors. Boats carrying bread, salt, fish and other foodstuffs continually landed on the islands. Thanks to this help, the rebels not only successfully repelled the attacks of the besiegers, but also made bold forays themselves, which were usually led by I. Voronin and S. Vasilyev, the chosen people's centurions. The construction of the fortifications was led by the fugitive Don Cossacks Pyotr Zapruda and Grigory Krivonoga, experienced in military affairs.

The entire civilian population of Solovki was armed and organized in a military manner: divided into tens and hundreds with the corresponding commanders at their head. The besieged significantly fortified the island. They cut down the forest around the pier so that no ship could approach the shore unnoticed and fall into the firing range of the fortress guns. The low section of the wall between the Nikolsky Gate and the Kvasoparennaya Tower was raised with wooden terraces to the height of other sections of the fence, a low Kvasopairennaya Tower was built on, and a wooden platform (roll) was built on the Drying Chamber for installing guns. The courtyards around the monastery, which allowed the enemy to secretly approach the Kremlin and complicate the defense of the city, were burned. Around the monastery it became “smooth and even.” In places where there was a possible attack, they laid boards with nails and secured them. A guard service was organized. A guard of 30 people was posted on each tower in shifts, and the gate was guarded by a team of 20 people. The approaches to the monastery fence were also significantly strengthened. In front of the Nikolskaya Tower, where most often it was necessary to repel the attacks of the royal archers, trenches were dug and surrounded by an earthen rampart. Here they installed guns and built loopholes. All this testified to the good military training of the leaders of the uprising and their familiarity with the technology of defensive structures.

After the suppression of the peasant war by S. T. Razin, the government took decisive action against the Solovetsky uprising. In the spring of 1674, the third voivode, Ivan Meshcherinov, arrived on Solovetsky Island. During the final period of the struggle, up to 1,000 archers with artillery were concentrated under the walls of the monastery.

In the summer-autumn months of 1674 and 1675. There were stubborn battles near the monastery, in which both sides suffered significant losses. From June 4 to October 22, 1675, the losses of the besiegers alone amounted to 32 people killed and 80 people wounded.

Due to the brutal blockade and continuous fighting, the number of defenders of the monastery also gradually decreased, supplies of military materials and food products were depleted, although the fortress could defend itself for a long time. On the eve of his fall, the monastery had, according to defectors, grain reserves for seven years, according to other sources - for ten years, and cow butter for two years. Only vegetables and fresh produce were in short supply, which led to an outbreak of scurvy. 33 people died from scurvy and wounds.

The Solovetsky Monastery was not taken by storm. He was betrayed by traitorous monks. The defector monk Feoktist led a detachment of archers into the monastery through a secret passage under the drying rack near the White Tower. Through the tower gates they opened, the main forces of I. Meshcherinov burst into the fortress. The rebels were taken by surprise. A wild massacre began. Almost all the defenders of the monastery died in a short but hot battle. Only 60 people survived. 28 of them were executed immediately, including Samko Vasiliev and Nikanor, the rest - later.

The destruction of the Solovetsky Monastery took place in January 1676. This was the second blow to the popular movement after the defeat of the peasant war by S. T. Razin. Soon after the suppression of the uprising, the government sent trustworthy monks from other monasteries to Solovki, ready to glorify the tsar and the reformed church.

Solovetsky uprising 1668–1676 was the largest anti-serfdom movement of the 17th century after the peasant war of S. T. Razin.

Solovetsky uprising 1668–1676 showed the government the strength of the monastery-fortress and at the same time convinced it of the need to show greater restraint and caution in arming the outlying islands.

From the book Rus' and the Horde. Great Empire of the Middle Ages author4. The Great Troubles of the 16th–17th centuries as the era of the struggle of the old Russian Horde dynasty with the new pro-Western Romanov dynasty. The end of the Russian Horde in the 17th century. According to our hypothesis, the entire “reign of Ivan the Terrible” - from 1547 to 1584 - is naturally divided into FOUR different

From the book Reconstruction of World History [text only] author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich8.3.6. THE END OF THE OPRICHNINA AND THE DEFEAT OF THE ZAKHARINS IN THE 16TH CENTURY. WHY THE ROMANOVS DISTORTED RUSSIAN HISTORY IN THE 17TH CENTURY The famous oprichnina ends with the defeat of Moscow in 1572. At this time, the oprichnina itself is being destroyed. For our analysis of these events, see [nx6a], vol. 1, p. 300–302. As the documents show,

From the book Book 1. New chronology of Rus' [Russian Chronicles. "Mongol-Tatar" conquest. Battle of Kulikovo. Ivan groznyj. Razin. Pugachev. The defeat of Tobolsk and author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich4. The Great Troubles of the 16th–17th centuries as the era of the struggle between the Russian-Mongolian-Horde old dynasty and the new Western dynasty of the Romanovs. The end of the Russian-Mongolian Horde in the 17th century. Most likely, the entire period of “Grozny” from 1547 to 1584 is naturally divided into FOUR different

From the book New Chronology and the Concept of the Ancient History of Rus', England and Rome author Nosovsky Gleb VladimirovichThe Great Troubles of the 16th–17th centuries as the era of the struggle between the Russian-Mongolian-Horde old dynasty and the new Western dynasty of the Romanovs. The end of the Russian-Mongol Horde in the 17th century According to our hypothesis, the entire period of “Grozny” from 1547 to 1584 is naturally divided into

From the book Pugachev and Suvorov. The Mystery of Siberian-American History author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich5. What did the word “Siberia” mean in the 17th century? Substitution of the name “Siberia” after the defeat of Pugachev. Shifting the borders between St. Petersburg Romanov Russia and Tobolsk Moscow Tartary in the 18th century. In our books on chronology, we have repeatedly said that

From the book Rus'. China. England. Dating of the Nativity of Christ and the First Ecumenical Council author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich author Team of authorsENGLAND IN THE 17TH CENTURY ENGLAND DURING THE RULE OF THE FIRST STEWARTS The founder of the new dynasty, James I Stuart (1603–1625), united England, Scotland and Ireland under his rule, laying the foundation for the triune kingdom - Great Britain. However, differences soon emerged between

From the book World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 3: The World in Early Modern Times author Team of authorsFRANCE IN THE 17TH CENTURY THE EDICT OF NANTES AND THE REVIVAL OF THE COUNTRY In 1598, having concluded the Peace of Vervins with Spain and ending the era of long religious wars with the publication of the Edict of Nantes, the French monarchy of the first king from the Bourbon dynasty, Henry IV (1589–1610), entered a period

From the book World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 3: The World in Early Modern Times author Team of authorsIRAN IN THE 17TH CENTURY

From the book World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 3: The World in Early Modern Times author Team of authorsJAPAN IN THE 17TH CENTURY At the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th centuries. the country was unified, the era of the “warring provinces” (1467–1590) (sengoku jidai) ended, and in the 17th century. The long-awaited peace came to the country. After the victory in 1590 over the powerful Hojo clan under the rule of Toyotomi Hideyoshi

From the book World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 3: The World in Early Modern Times author Team of authorsENGLAND IN THE 17TH CENTURY English bourgeois revolution of the 17th century / ed. E.A. Kosminsky and Y.A. Levitsky. M., 1954. Arkhangelsky S.I. Agrarian legislation of the English Revolution. 1649–1660 M.; L., 1940. Arkhangelsky S.I. Peasant movements in England in the 40s and 50s. XVII century M., 1960. Barg M.A.

From the book World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 3: The World in Early Modern Times author Team of authorsFRANCE IN THE 17TH CENTURY Lyublinskaya A.D. France at the beginning of the 17th century. (1610–1620). L., 1959. Lyublinskaya A.D. French absolutism in the first third of the 17th century. M.; L., 1965. Lyublinskaya A.D. France under Richelieu. French absolutism in 1630–1642 L., 1982. Malov V.N. J.-B. Colbert. Absolutist bureaucracy and

From the book World History: in 6 volumes. Volume 3: The World in Early Modern Times author Team of authorsITALY IN THE 17TH CENTURY History of Europe. M., 1993. T. 3. Part 2, ch. 7. Rutenburg V.I. Origins of the Risorgimento. Italy in the XVII–XVIII centuries. L., 1980. Callard S. Le prince et la republique, histoire, pouvoir et 8été dans la Florence des Medicis au XVIIе siècle. P., 2007. Montanelli /., Gervaso R. L’ltalia del seicento (1600–1700). Milano, 1969. (Storia

author Istomin Sergey Vitalievich From the book Book 1. Biblical Rus'. [The Great Empire of the XIV-XVII centuries on the pages of the Bible. Rus'-Horde and Ottomania-Atamania are two wings of a single Empire. Bible fuck author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich21. The end of the oprichnina and the defeat of the Zakharyins in the 16th century Why the Romanovs distorted Russian history in the 17th century It is known that the oprichnina, during which the Purim terror was launched, ends with the famous Moscow defeat of 1572. At this time, the oprichnina itself is being destroyed. As shown

From the book I Explore the World. History of Russian Tsars author Istomin Sergey VitalievichAlexey Mikhailovich - Quiet, Tsar and Great Sovereign of All Rus' Years of life 1629–1676 Years of reign 1645–1676 Father - Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov, Tsar and Great Sovereign of All Russia. Mother - Princess Evdokia Lukyanovna Streshneva. Future Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich Romanov, eldest son

Solovetsky uprising (1668 and 1676)

Solovetsky uprising (1668 and 1676)

Historians usually call the Solovetsky uprisings the opposition of Old Believers’ supporters to Nikon’s church reform.

The participants were representatives of different social strata:

· simply dissatisfied with the changes;

· alien dependent people;

· monastery workers and novices;

· ordinary monks who fought against the growing power of the patriarch and monks;

· the top of the monastery elders who opposed radical innovations, etc.

Total number of participants: about five hundred people.

The initial stage of the confrontation between the brethren of the Solovetsky Monastery and the Moscow authorities dates back to 1657, when this monastery was one of the most economically independent and rich, due to the wealth of natural resources and great distance from the center of the state.

So, in the new books brought to the monastery for worship, the Solovki residents discovered “many crafty innovations” and “ungodly heresies,” which the monks flatly refused to introduce into their monastery. So, starting from 1663 to 1668, nine petitions and many messages were sent to the king, in which the truth of only the old faith was proven using real examples.

The next stage began on the twenty-second of June 1668. On this day, the king sent a detachment of archers to pacify the monks. From this time on, a passive blockade of the monastery began. It was in response to the blockade that the monks began an uprising “for the true right faith,” taking up defenses around the fortress.

The rebels were sympathized with and also helped by peasants, fugitive archers, newcomers and working people, as well as participants in the peasant war led by Stepan Razin. But even during these years, Moscow did not try to send large forces to the monks to suppress the rebellion. At the same time, the uprising continued and the leadership of the monastery advocated negotiations with the government, which, however, could not lead to anything. As a result, the king increased the army and gave the order to “root out the rebels.”

The last stage was repeated attempts to storm the fortress. Even despite the number (more than a thousand people) of the archers, the monks did not give up. During the assaults, the monastic priorities changed and they were already speaking out not only against the introduction of “heresies,” but also against the existing king in general.

The confrontation ended in early 1676, when a fugitive monk told the archers about a secret passage to the monastery.