The medieval battle of Rakovor took place in 1268. This battle is one of the many episodes of the Northern Crusades, as well as the struggle between the German knights and the Russian principalities for influence in the Baltic.

The history of these complex relationships is best known thanks to the wars of the battle and the Battle of the Ice. Against the backdrop of these events, the Battle of Rakovor remains almost invisible. Nevertheless, it was an important battle, in which huge squads took part.

background

Baltic tribes lived compactly on the territory of modern Latvia and Estonia for several centuries. In the XI century, the territorial expansion of Rus' began in this region, but it almost immediately ended due to the beginning of political fragmentation in the East Slavic state. Soon German colonists appeared in the Baltics. They were Catholic by religion, and the Popes of Rome organized the Crusades to baptize the pagans.

So, in the XIII century, the Teutonic Empire appeared and Sweden and Denmark were their allies. In Copenhagen, a military campaign was organized to capture Estonia (modern Estonia). Crusaders appeared on the border of Russian principalities (primarily Pskov and Novgorod). In 1240, the first conflict broke out between the neighbors. During these years, Rus' was under attack from the Mongol hordes, who came from the eastern steppes. They destroyed many cities, but never reached Novgorod, which was too far to the north.

Struggle of Alexander Nevsky with the Western Threat

This circumstance helped Nevsky to gather fresh forces and take turns repelling the Swedes and the German crusaders. Alexander successively defeated them in the Battle of the Neva (1240) and the Battle of the Ice (1242). After the success of Russian weapons, a truce was signed, but it was clear to all diplomats that the agreement was temporary, and in a few years the Catholics would strike again.

Therefore, Alexander Nevsky began to look for allies in the fight against the crusaders. He managed to establish contacts with the Lithuanian prince Mindovg, for whom the German expansion was also a serious threat. The two rulers were close to making an alliance. However, in 1263 the Lithuanian and Novgorod princes died almost simultaneously.

Personality of Dovmont

The famous Rakovor battle left to the descendants the glorious name of Dovmont, who led the Pskov army in the battle against the Catholics. This prince was from Lithuania. After the death of Mindaugas, he took part in his homeland. He failed to hold any inheritance, and he was expelled by his compatriots. Even then, Dovmont was known for his courage. His personality interested the inhabitants of Pskov, who, after the death of Alexander Nevsky, needed an independent defender from their neighbors. Dovmont gladly agreed to serve the city and in 1266 became the Pskov prince and governor.

This election was facilitated by the unique political system that developed in the north of Rus'. Pskov and Novgorod differed from other East Slavic cities in that their rulers were appointed by the decision of a popular vote - veche. Because of this difference, the inhabitants of these lands often clashed with another Russian political center - Vladimir-on-Klyazma, where hereditary representatives of the Rurik dynasty ruled. They paid tribute to the Mongols and periodically sought the same taxes from Novgorod and Pskov. However, no matter how difficult the relations between them were, the main threat to the Russian republics in those years came from the West.

By this time, a whole conglomerate of Catholic states had formed in the Baltic States, which acted in concert, seeking to conquer and baptize the local pagans, as well as defeat the Slavs.

Novgorod campaign in Lithuania

In 1267, the Novgorodians organized a campaign against the warlike Lithuanians, who did not leave their borders alone. However, already on the way to the west, a conflict began among the commanders, and the original plan was changed. Instead of going to Lithuania, the Novgorodians went to Estonia, which belonged to the Danish king. The Battle of Rakovor was the culmination of this war. The formal reason for the campaign was regular news that Russian merchants were oppressed in the markets of Revel, which belonged to the Danes.

However, with all the desire, it would be difficult for the Novgorodians to resist the Catholic Union. The first campaign in 1267 ended before it even started. The army returned home, and the commanders decided to ask for help from the Grand Duke of Vladimir Yaroslav Yaroslavich. On the banks of the Volkhov, he had a governor, agreed with local citizens. He was the nephew of Alexander Nevsky Yuri Andreevich. It was this prince who was the main commander in the Russian army when the Battle of Rakovor happened.

Union of Russian Princes

Russian blacksmiths began to forge new weapons and armor. Yuri Andreevich invited other Slavic princes to join his campaign. Initially, the backbone of the army was the Novgorod army, supplemented by Vladimir detachments, which were given to the governor Yaroslav Yaroslavich. The battle of Rakovor was supposed to test the strength of allied relations between neighbors.

In addition, other princes joined the Novgorodians: Dmitry, who ruled in Pereyaslavl; the children of the Vladimir prince Svyatoslav and Mikhail, with whom the Tver squad arrived; as well as the Pskov prince Dovmont.

While the Russian knights were preparing for an imminent war, Catholic diplomats did everything to outwit the enemy. In the midst of the gathering of troops, ambassadors from Riga arrived in Novgorod, representing the interests of the Livonian Order. It was a trick. The ambassadors urged the Russians to make peace in exchange for the Order not supporting the Danes in their war. While the Novgorodians were negotiating with the inhabitants of Riga, they were already sending troops to the north of their possessions, preparing to organize a trap.

Raid in the Baltics

On January 23, the united Russian squad left Novgorod. The battle of Rakovor was waiting for her. The year 1268 began with the usual cold winter, so the army quickly crossed the icy Narva, which was the border between the two countries. The main target of the campaign was the strategically important fortress of Rakovor. The Russian army moved slowly, being distracted by the robberies of the defenseless Danish territory.

The battle of Rakovor took place on the river bank, the exact location of which has not yet been established. Historians argue with each other because of the confusion of the sources, which indicate different toponyms. One way or another, the battle took place on February 18, 1268 in northern Estonia, not far from the town of Rakovora.

Preparing for battle

On the eve of the clash, the Russian command sent scouts in order to more accurately find out about the size of the enemy. Returning rangers reported that there were too many warriors in the enemy camp for the Danish army alone. Unpleasant guesses were confirmed when the Russian knights saw the knights of the Livonian Order in front of them. This was a direct violation of those peace agreements that the Germans agreed with the Novgorodians on the eve of the campaign.

Despite the fact that the enemy army was twice as strong as the commanders of the Russian army expected, the Slavs did not flinch. According to various chronicles, there was parity on the battlefield - there were about 25 thousand people on each side.

German tactics

The battle order of the Catholic army was formed according to the favorite Teutonic tactics. It consisted in the fact that in the center, heavily armed knights stood in the form of a wedge directed towards the enemy.

To their right were the Danes. On the left is the Riga militia. The flanks were supposed to cover the attack of the knights. The Battle of Rakovor in 1268 did not become an attempt for the Catholics to rethink their standard tactics, which let them down during the war with Alexander Nevsky.

The construction of the Russian army

The Russian army was also divided into many regiments, each of which was led by one of the princes. On the right stood Pereyaslavtsy and Pskovites. In the center were the Novgorodians, for whom the Battle of Rakovor in 1268 became a decisive episode in the struggle against the Germans. To their left was the Tver squad, sent by the Vladimir prince.

In the structure of the Russian army, its main drawback was laid. The courage and skills of the army were powerless before the uncoordinated actions of the generals. The Russian princes were arguing over who was legally the head of the entire military campaign. According to the dynastic position, Dmitry Alexandrovich was considered to be him, but he was young, which did not give him authority in the eyes of his older comrades. The most experienced strategist was the Lithuanian Dovmont, but he was only a Pskov governor and, moreover, did not belong to the Rurik family.

Therefore, throughout the battle, the Russian regiments acted at their own discretion, which made them more vulnerable to the crusaders. The battle of Rakovor, the causes of which were the war between the Novgorodians and the Catholics, only further aggravated the rivalry between the Slavic princes.

Beginning of the battle

The battle of Rakovor began with the attack of the German knights. On February 18, it was to be decided which side of the conflict would win the war. While the Germans were moving forward in the center, the Tver and Pereyaslav squads hit the enemies on their flanks. The Pskov regiment also did not remain idle. His knights entered into battle with the army belonging to the Bishop of Dorpat.

The most serious blow fell on the Novgorodians. They had to deal with the famous German "pig" attack, when the knights in a single march developed breakneck speed and swept the enemy from the battlefield. The army of Yuri Andreevich prepared in advance for such a turn of events, lining up defensive echelons. However, even tactical tricks did not help the Novgorodians withstand the blow of the cavalry. It was they who faltered first, and the center of the Russian army noticeably sank and fell down. Panic began, it seemed that the battle of Rakovor was about to end. The forgotten victory of Russian weapons was achieved thanks to the courage and perseverance of Dmitry Alexandrovich.

His regiment managed to defeat the Riga militia. When the prince realized that things were taking a bad turn in the rear, he quickly turned his army back and hit the Germans from the rear. They did not expect such a daring attack.

Delivery of the convoy

By this time, the governor of Novgorod, Yuri Andreevich, had already fled from the battlefield. Those few daredevils from his army who still remained in the ranks joined Dmitry Alexandrovich, who hastened to help, in time. On the other flank, the Danes finally gave up their positions and rushed to run after the militias of the deceased bishop. The Tver squad did not come to the aid of the Novgorodians in the center, but began to pursue the retreating opponents. Because of this, the Russian army failed to organize worthy resistance to the German "pig".

Toward evening, the knights repulsed the attack of the Pereyaslavites and again began to press on the Novgorodians. Finally, already at dusk, they captured the Russian convoy. It also contained siege engines, which were prepared for the siege and assault of Rakovor. All of them were promptly destroyed. However, this was only an episodic success for the Germans. The battle of Rakovor, in short, stopped only because the daylight hours ended. The armies of rivals laid down their arms for the night and tried to rest in order to finally sort out their relationship at dawn.

Already at night, the Tver regiment returned to its position, which pursued the Danes. He was joined by the surviving warriors from other units. Among the corpses, they found the body of the Novgorod posadnik Mikhail Fedorovich. A little later, at a council, the commanders-in-chief discussed the idea of attacking the Germans in the dark and recapturing the baggage train by surprise. However, this idea was too adventurous, because the warriors were tired and exhausted. It was decided to wait until morning.

At the same time, the surviving German regiment, the only combat-ready formation from the original Catholic conglomerate, realized the plight of its situation. His commanders decided to retreat. Under the cover of night, the Germans left the Russian convoy without taking any booty with them.

Consequences

In the morning, the Russian army realized that the Germans had fled. This meant that the battle of Rakovor had ended. Where the slaughter took place, hundreds of corpses lay there. The princes stood on the battlefield for three more days, burying the dead, and also not forgetting to collect trophies. The victory was for the Russian army, but due to the fact that the Germans destroyed the siege machines, a further march towards the fortress of Rakovor became pointless. It was not possible to capture the fortifications without special devices. It was possible to resort to a long and exhausting siege, but this was not in the plans of the Novgorodians from the very beginning.

Therefore, the Russian regiments returned to their homeland, to their cities. The only one who did not agree with this decision was the one who, together with his squad, continued the raid on the unprotected places of Pomorie. The battle of Rakovor, which claimed the lives of about 15 thousand people, still remains an important milestone in the confrontation between the military-monastic orders of Catholics and the Russian principalities.

Pthe history of events is as follows: In 1268, the Novgorodians went on a campaign against the Lithuanians, but on the way they changed their minds and turned in a completely different direction - to the Danish possessions in Livonia. The Lithuanians threatened the Pskov lands, but the Danes could profit well without fear of getting a worthy rebuff.

Novgorodians devastated the surroundings of Rakovor, but they could not take the city. Having lost seven people on the campaign, they returned home very dissatisfied with the failure that had befallen them, and immediately proceeded to prepare a new invasion of Danish possessions. No longer relying only on their own strength, the Novgorodians sent to the Nizov princes with a proposal to take part in the campaign against Rakovor. They invited craftsmen who knew how to make siege weapons. Residents of Riga, Derptians, Livonian knights, alarmed by large-scale military preparations, sent ambassadors with whom the Novgorodians agreed that the Livonian Germans would not help the Danes.

The campaign began with the traditional extermination of the Estonians. In one place, the Russians discovered a cave in which many local residents hid. It is not known how the natives prevented the Russians and why they decided to destroy them. “For three days the regiments stood in front of the cave and could not get to the Chud in any way; Finally, one of the craftsmen who was with the cars guessed to turn on the water: by this means, the Chud was forced to leave her shelter, and was killed. (Soloviev, SS., vol. 2, p. 162)

After the battle, without taking Rakovor, the squads of the Russian princes, having stood for three days “on the bones” (on the battlefield) as a sign of victory, simply went home without making any attempts to gain a foothold in the territory of Livonia. Only the Pskovites, led by their restless prince Davmont, remained to plunder more. “Davmont with the Pskovites wanted to take advantage of the victory, devastated Livonia to the very sea and, returning, filled their land with many full” (Soloviev, SS., vol. 2, p. 163).

Why did the Rakovor battle make such a strong impression on contemporaries? Firstly, in terms of scale, the Battle of Rakovor was much larger than the Battle on the Ice. In the battle near Rakovor, not only the inhabitants of the Derpt bishopric fought with the Russians, but “the whole German land”, i.e. troops of all states of the Livonian Confederation, who came to the aid of the Danes, against whom the Russians started this campaign. The Russian regiments were led not by two princes, but by as many as seven. Accordingly, the number of Russian troops was two to three times more than in 1242 with Alexander and Andrei Yaroslavich.

Secondly, the battle was so fierce and bloody that, according to the NPL, only the Novgorodians lost all their commanders in it - the posadnik and the thousandth, thirteen of the most noble citizens, "and black people without number." How many soldiers from other Russian detachments died, the Novgorod chronicler, of course, is not interested. It must be assumed that their losses were no less heavy.

At the same time, domestic history textbooks are silent about the Battle of Rakovor on a larger scale than “the largest battle in the history of the Middle Ages” (as the Battle on the Ice is modestly called). Why? Yes, because it does not fit into the theory of Western aggression against Rus'. The Danes, whose possessions were struck, did not pose any threat to Novgorod and Pskov. Moreover, they did not threaten the security of Tver, Suzdal and Pereslavl, whose squads also came to the walls of Rakovor. The Russians were not going to seize the Livonian lands, or, as it was customary to say in Soviet times, to free the enslaved local residents from the heavy oppression of the Catholic Church and Western feudal lords. It was another predatory campaign, one of those about which Solovyov wrote: "they entered the German land and began to devastate it according to custom" (SS., vol. 2, p. 162). Precisely predatory, because he did not pursue any political or military goals.

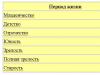

So, what do we have in the bottom line:

The invasion of a huge Russian army forced the sworn friends of the Danes and Livonian Germans to unite, who were previously in a state of permanent war over the division of Estonian lands.

The Estonians once again received an object lesson of who is their enemy and who is their defender.

Despite the overwhelming superiority of the aggressor's forces (at least three times), the allies boldly attacked him and inflicted such losses on the enemy, after which the seekers of easy prey had to abandon their plans and return home.

- "Broken" "adversaries" in the following year struck back at Pskov. The Russian principalities and the "big brother" Novgorod itself, the organizer and participants in the attack on the Danish possessions, did not suffer, as usual, giving the honorable right to pay off their accomplices to the Pskovites.

The defeat at Rakovor was the last major invasion of the Novgorodians into Livonia. It stopped more than a century of expansion of Rus' to its western neighbors. Since that time, Novgorod has been trying to be friends with Livonia against its primordial enemy - the “grassroots” land and its new center of Moscow.

The grandiose and forgotten Battle of Rakovor took place on February 18, 1268 between the united army of North-Eastern Rus' on the one hand and the forces of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, the Catholic bishops of the eastern Baltic and the Danish king on the other.

This is one of the largest battles in the history of medieval Europe, both in terms of the number of participants and the number of soldiers who died in it. After the almost simultaneous death of Alexander Nevsky and the Lithuanian king Mindovg in 1263, the union of Vladimir Rus' and Lithuania against the Teutonic Order, which had firmly established itself by that time in the Eastern Baltic and seriously threatened the very existence of the latter, broke up.

In the Lithuanian state, after the death of Mindovg, military clashes began between his heirs and associates, as a result of which most of them died, and for example, the Nalsha prince Dovmont (Daumantas), was forced to leave his homeland and, together with his family and squad, went to Pskov, where he was hired as a governor. In general, the young Lithuanian state, having lost its central power, again broke up into separate principalities and did not manifest itself in the foreign policy arena for a long time, limiting itself to the defense of its own land and episodic raids on the territory of its neighbors. However, these raids did not pursue political goals.

Rus', unlike Lithuania, after the death of Alexander Nevsky, avoided serious strife. Novgorod meekly accepted the reign of Yaroslav Yaroslavovich, who became the Grand Duke of Vladimir, several successful campaigns of the Pskov governor Dovmont, baptized in the Orthodox rite under the name of Timothy, to Lithuania (1265 - 1266) finally eliminated the Lithuanian threat to the western borders of Rus'. The most serious danger in the north for Rus' was now the Catholic enclave in the lands of Livonia and Latgale (modern Estonia and Latvia).

The structure of this enclave was quite complex. The north of Livonia was occupied by the subjects of the king of Denmark, the "king's men", they owned the cities of Revel (Kolyvan, Tallinn) and Wesenberg (Rakovor, Rakvere), as well as all the lands from the Narva River to the Gulf of Riga along the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland to a depth of 50 km. In central and southern Livonia, as well as Latgale, the possessions of the Order and the Livonian archbishops, whose nominal head was the Archbishop of Riga, were a fair patchwork. For example, Riga, Derpt (Yuryev, Tartu), Odenpe (Bear's Head, Otepää), Gapsal (Hapsalu) with its environs belonged to the archbishop, and Wenden (Cesis), Fellin (Viljandi) and other areas belonged to the Order. Between the Danes and the Order, as well as between the order and the archbishop, contradictions periodically arose, reaching even armed clashes, but it was by the mid-1260s that these contradictions were overcome and all three political forces were able to act as a united front. It would be at least strange if the enclave did not take advantage of this circumstance and did not try to expand its borders to the east.

Since the capture in 1226 by the crusaders of Yuryev, renamed Derpt or Dorpat by the invaders, they have repeatedly attempted to subjugate the lands lying east of Lake Peipus and the Narva River, that is, the territory occupied by the Izhora and Vod tribes, by that time, basically, already Christianized according to the Orthodox rite. However, at the same time, each time they ran into albeit sometimes disorganized, but always stubborn and fierce resistance of their eastern Orthodox neighbors - Veliky Novgorod and its outpost on the western borders - Pskov. In those cases when the princes of Vladimir Rus' came to the aid of these cities, the Crusaders' enterprises ended in heavy military defeats (the Battle of Yuryev in 1234, the Battle of the Ice in 1242, etc.). Therefore, another attempt to advance its influence to the east was prepared especially cunningly and carefully.

When and where exactly - in the office of the Archbishop of Riga or the Order, a plan of inflicting a military defeat on Novgorod by provoking its conflict with the Danes and subsequent intervention in this conflict, remains a mystery. Based on whose role in the implementation of this plan was the most active, then the Order should be recognized as its initiator. However, the handwriting itself, the style with which this plan was conceived, is rather characteristic of the papal office. Be that as it may, the plan was created, agreed upon and approved by all interested parties. Its essence was that the Danish side, as the weakest militarily, provokes Novgorod with its aggressive actions for a military campaign with limited forces in northern Livonia. In Livonia, the combined forces of the enclave will be waiting for the Novgorodians, the inevitable defeat of the core of the Novgorod army follows, after which, while the Novgorod community comes to its senses and gathers new forces, a series of lightning-fast captures of fortified points in the territory east of Narva and Lake Peipsi follows.

The formal reason for the conflict was the intensified oppression of Novgorod merchants in Reval, the capital of the "king's land". There have also been pirate attacks on merchant ships in the Gulf of Finland. For Novgorod, trade was the main source of income, so the Novgorod community reacted extremely painfully to such events. In such cases, internal disagreements faded into the background, the community consolidated, demanding an immediate and tough response from its leaders.

This happened at the end of 1267. The Novgorodians began to prepare for the campaign. Grand Duke Yaroslav Yaroslavovich tried to take advantage of these circumstances and wanted to lead the army gathered by the Novgorodians to Polotsk, which he planned to subdue to his influence. Under pressure from the Grand Duke's governor, Prince Yuri Andreevich, the united squads went on a campaign in the direction of Polotsk, but a few days away from Novgorod, the Novgorod squad staged a spontaneous veche. Novgorodians announced to the viceroy of the Grand Duke that they would not go to Polotsk or Lithuania. It must be assumed that Yuri Andreevich was extremely dissatisfied with this turn of affairs, however, the Novgorod governors still managed to convince the princely governor to join his squad to the general campaign, the purpose of which at the same veche were elected, it would seem, weak and militarily defenseless Rakovor and Revel. The Russians swallowed the bait carefully thrown to them by the Order and Riga.

The Russian army was not prepared to storm a well-fortified stone castle, which at that time was Rakovor. The Russians devastated the surroundings, approached the castle, but having lost seven people while trying to take the city by an unexpected assault, “exile”, retreated. For a successful systematic assault, appropriate siege devices were needed, which the Russian army, which was originally going to rob the Polotsk and Lithuanian lands, did not stock up. The Russians retreated, the army returned to Novgorod.

An unexpected change in the direction of the campaign, the absence of convoys with siege equipment and, as a result, high speed of movement, as well as the fact that the Russian army practically did not linger near Rakovor - all this played an unexpectedly saving role for the Russians - the Catholics did not have time to intercept the Russian army. It seemed that the carefully calibrated plan of the enclave fell through, but immediately from Novgorod, from the permanent trade missions there, reports began to arrive in Livonia about a new campaign being prepared against Rakovor and Revel. The plan didn't fail, it was just delayed.

In the second campaign against Rakovor, the participation of much larger forces was planned. In Novgorod, weapons were intensively forged, in the courtyard of the Novgorod archbishop, craftsmen assembled siege equipment. Novgorodians managed to convince the Grand Duke Yaroslav Yaroslavovich of the need and benefit of the campaign in Livonia. Other princes of the Vladimir land also decided to take part in the campaign: Dmitry Alexandrovich Pereyaslavsky (son of Alexander Nevsky), Svyatoslav and Mikhail Yaroslavichi (sons of the Grand Duke) with the Tver squad, Yuri Andreevich (son of Andrei Yaroslavovich, brother of Nevsky), as well as Prince Dovmont with the Pskov squad. Without the direct approval of the Grand Duke, such a coalition, of course, could not take place. In addition, princes Konstantin and Yaropolk are named as participants in the campaign in the annals, but one can only say with certainty about their origin that they were Rurik. The force was quite impressive.

In the midst of preparations, ambassadors from the Archbishop of Riga arrive in Novgorod with a request for peace in exchange for non-participation in Novgorod's military operations against the Danes. “And the Germans sent their own ambassadors, residents of Riga, Veliazhans, Yuryevtsy, and from other cities, flatteringly saying:“ Peace be with you, overcome with Kolyvantsi and Rakovortsy, but we don’t pester them, but kiss the cross. And kissing the ambassadors of the cross; and there Lazor Moiseevich drove all of them to the cross, piskupov and God's nobles, as if not to help them with Kolyvan and Rakovor; (quote from chronicle). The leaders of the Novgorod community were not naive people and suspected the ambassadors of insincerity. To verify the honesty of their intentions, a plenipotentiary representative of the community, the boyar Lazar Moiseevich, was sent to Riga, who was supposed to swear in the top leadership of the Order and the Archbishopric of Riga, which he successfully did. In the meantime, troops were being drawn into northern Livonia from all the lands controlled by the enclave. The trap for the Russians was about to close.

On January 23, 1268, the Russian army in full force with a convoy and siege equipment left Novgorod, soon the Russians crossed Narva and entered the Livonian possessions of the Danish king. This time, the Russians were in no hurry, dividing into three columns, they systematically and purposefully engaged in the destruction of hostile territory, slowly and inevitably approaching the first goal of their campaign - Rakovor.

The chronicle describes in detail the episode with the discovery by the Russians of a cave in which the locals took refuge. For three days, the Russian army stood near this cave, not wanting to storm it, until the “perverse master” managed to let water into the cave. How this operation was carried out and where this cave could be located is not known for certain. We only know that the "chud" from the cave "begone" and the Russians "issekosha ih", and the booty found in this cave, the Novgorodians gave to Prince Dmitry Alexandrovich. There are no natural caves on the territory of northern Estonia that could accommodate more than 20-30 people. The fact that the Russian army spent on the siege and plunder of the shelter, in which hardly two dozen people could hide, indicates that the Russians were really in no hurry and approached the process of plundering northern Livonia very thoroughly.

The Russian army advanced through hostile territory without encountering any resistance, the forces were so great that the military campaign seemed like a pleasure trip. Nevertheless, it is likely that the leaders of the campaign received information that the enemy army had entered the field and was preparing to fight, since immediately before the clash, the army was again gathered into a single fist.

About where exactly the battle took place, historians are still arguing. The chronicle says that the meeting with the united army of the enclave took place on the Kegol River. This toponym has not survived to this day, most researchers associate it with a small river Kunda near Rakvere. However, there is another opinion on this issue, which seems to me to a greater extent justified. This refers to the hypothesis that the Rakovor battle took place 9 km northeast of Kunda - on the Pada River near the village of Makholm (modern village of Viru-Nigula). There are various arguments in the literature both in favor of one and in favor of another place. The decisive argument seems to me that it was the crossing over the Pada that was the most convenient place to wait for the approach of the Russian troops. Northern Estonia is still full of intermittent swamps and forested hills. The only convenient place for laying a permanent road was, and still is, the coastal strip along the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, along which the Tallinn-Narva highway still passes. Before crossing the Pada River, this road comes out of a kind of “defile”, several kilometers wide, bounded by wooded and swampy areas from the south, and by the Gulf of Finland from the north, and it is very problematic to pass this place when moving from the east towards Rakvere. Moreover, after crossing Pada, the road turns south, moving away from the coast, and thus the army waiting for the enemy would have to disperse its forces for reconnaissance and guard duty on a wide front, while, while waiting for the enemy near Makholm, the commander could afford to concentrate the bulk of the troops in this place without dispersing forces.

So, on the morning of February 18, 1268, the Russian army broke camp and advanced in full strength towards the village of Makholm in order to cross the Pada. There are about 20 kilometers left to Rakovor. Equestrian intelligence has already reported that on the western bank of the Pada there is an enemy army in numbers that clearly exceed the capabilities of the “Kolvan Germans”, but the Russian confidence in their numerical superiority, as well as the agreements with Riga and the Order sealed with a cross, gave significant reasons for optimism. The Russian command decided to give battle. The regiments were prepared, the armor was raised, the strings were planted, the bows were stretched. The trap closed.

What did the Novgorod thousand Kondrat and the posadnik Mikhail Fedorovich feel when they saw the total army of the entire “German land” lined up on the banks of the Pada, ready for battle? What did the Russian princes think, Litvin Dovmont? One thing is for sure: despite the fact that the presence in the enemy army of "God's nobles", "vlizhan", "Yuryevites", and all the rest, whose leaders a month ago "kissed the cross" not to participate in hostilities, was certainly unexpected for them, there was no confusion in the Russian army.

The Germans and Danes occupied the western bank of the Pada, standing on the hillside, on top of which the commander was probably located. The flat slope, gently descending into the valley, was very convenient for the attack of heavy knightly cavalry. It was decided to let the Russians cross the river, and then attack from top to bottom. A swampy stream still flows along the western bank of the Pada in this place, which became the natural divider of the two troops before the battle. The banks of this small stream became the very place where two huge armies collided. The old-timers of Viru-Nigul still call it “evil” or “bloody”…

There is no reliable information about the number of troops participating in the battle of Rakovor. The Livonian rhymed chronicle speaks of thirty thousand Russians and sixty times smaller (that is, five thousand) allied army. Both the first and second figures cause more than serious doubts. Without going into details of the discussion that unfolded about the number of troops participating in the battle, I will say that the most plausible opinion seems to me that both the Russian and German troops numbered about fifteen to twenty thousand people.

The basis of the battle order of the troops of the enclave was the knights of the Teutonic Order, who entered the battlefield in their favorite formation - a wedge or "pig", which indicates the offensive nature of the battle on the part of the Germans. The right flank of the "pig" was defended by the Danes, the archbishop's troops and the militia lined up on the left. Bishop Alexander of Yuryevsky (Derptsky) carried out the general command of the army of the enclave.

The Russian army was built as follows. On the right flank stood the Pereyaslav squad of Prince Dmitry Alexandrovich, behind it, closer to the center, the Pskov squad of Prince Dovmont, in the center - the Novgorod regiment and the governor's squad of Prince Yuri Andreevich, on the left flank stood the squad of Tver princes. Thus, the most numerous Novgorod regiment stood up against the "pig". The main problem of the Russian army was that it lacked unity of command. Dmitry Alexandrovich was the senior prince among the princes, but he was young and not so experienced. Prince Dovmont was distinguished by mature age and great experience, but he could not claim leadership, due to his position - in fact, he was simply the governor of the Pskov detachment and he was not a Rurikovich. Prince Yuri Andreevich, the Grand Duke's governor, did not enjoy authority among his comrades-in-arms, while the leaders of the Novgorod community did not have princely dignity and could not command princes. As a result, the Russian detachments acted without obeying a single plan, which, as we will see, had a detrimental effect on the outcome of the battle.

The battle began with an attack by a German "pig" that fell on the center of the Novgorod regiment. At the same time, both flanks of the allied forces were attacked by the Tver and Pereyaslav regiments. The army of the Bishop of Dorpat entered into battle with the Pskov detachment. The Novgorod regiment had the hardest time of all - the armored wedge of the knightly cavalry, when struck shortly, developed tremendous strength. Apparently, the Novgorodians, familiar with this system firsthand, deeply echeloned their battle formation, which gave it additional stability. Nevertheless, the pressure on the Novgorod regiment was so serious that at some point the regiment’s formation broke up, panic began, Prince Yuri Andreevich, together with his squad, succumbed to a panic mood and fled from the battlefield. The defeat of the Novgorod regiment seemed inevitable, but at that moment Prince Dmitry Alexandrovich showed himself in the most commendable way - he abandoned the pursuit of the defeated Livonian militia, gathered around him as many soldiers as he could and made a swift attack on the flank of the advancing German wedge.

The fact that such an attack was possible, given the initial position of the regiments, suggests that by this point the militia and the episcopal detachment were already defeated and fled from the battlefield, freeing Dmitry space for an attack. The author of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle also indirectly testifies to the rapid defeat of the bishop's regiment, mentioning the death of its leader, Bishop Alexander, at the very beginning of the battle. Probably, far from the entire Pereyaslav squad took part in the attack on the "pig", the main part of it, apparently, was carried away by the pursuit of the retreating, Prince Dmitry was able to collect only a small part, which saved the "pig" from complete destruction. However, the German formation faltered, which allowed the Novgorod regiment to regroup and continue organized resistance.

Having repelled the attack of the Pereyaslav squad, the Teutons continued their attack on the Novgorod regiment. The battle began to take on a protracted character, its epicenter moved from one side to the other, someone ran forward, someone back, attacks rolled in waves one on another. The Danish detachment trembled and fled from the battlefield, the Tver squad rushed to pursue him.

By the end of daylight, a few hours after the start of the battle, the Novgorod regiment finally crumbled, however, the Teutons were so tired that there could be no talk of pursuing the retreating Russians. The Teutons limited themselves to an attack on the Russian convoy, which they managed to capture. Perhaps this was the key moment of the entire campaign, since it was in the convoy that there were siege devices designed to storm Rakovor and Revel. There is no doubt that these devices were immediately destroyed.

With the onset of dusk, the princely squads began to return, pursuing the defeated detachments of Danes, Livonians and Germans, the Novgorod regiment gathered again, regrouped and was ready to attack. In the daytime battle, the Novgorod posadnik Mikhail Fedorovich died, fifteen more Novgorod "high-ranking men" listed in the annals by name, the thousandth Kondrat went missing. The surviving commanders proposed to carry out a night attack and recapture the convoy from the Teutons, but the council decided to attack in the morning. During the night, the Teutons, aware of their extremely dangerous situation, left. The Russians did not pursue them.

The battle of Rakovor is over. The Russian army for another three days, emphasizing their victory, stood on the battlefield - they picked up the wounded, buried the dead, collected trophies. It is unlikely that the losses of the Russians were too great - in the medieval battle "face to face" the main losses were borne by the losing side precisely during the pursuit by the winners, and not during the direct "showdown". The Russian troops did not run from the battlefield near Rakovor, which cannot be said about the majority of their opponents “and drove them to the city three ways, seven miles, as if they had no urine or horses to step on corpses” (quote from the chronicle), that is, the horses of Russian soldiers could not move because of the abundance of corpses lying on the ground. There was probably no question of continuing the campaign, since the Russian convoy was destroyed, and at the same time the engineering devices necessary for the siege were lost, which could not be restored on the spot, otherwise, why would they be taken from Novgorod. Without the assault on Rakovor, the campaign lost all meaning, turned, in fact, into a repetition of the autumn sortie. Only Prince Dovmont was not satisfied with the results achieved, who continued the campaign with his retinue, “and captivate their land and to the sea and conquer Pomorie and return again, fill your land full” (quote from the chronicle). Some modern researchers believe (and perhaps not entirely unreasonably) that there was no additional sortie by Dovmont, and the annalistic record refers to the Rakovor campaign itself as part of the entire Russian army, but their position does not convince me personally. Dovmont proved himself to be a fearless and tireless warrior, an outstanding strategist and tactician, with his small but mobile and experienced squad, hardened in numerous campaigns and battles, the backbone of which was made up of people from Lithuania, personally devoted to their leader, he could afford to pass with fire and sword through unprotected enemy territory. Indirect confirmation that Dovmont's sortie did take place can also be the fact that the return campaign of the Teutonic Order against Rus' in June 1268 was aimed precisely at Pskov.

Each of the parties involved in the battle attributes the victory to itself. German sources speak of five thousand dead Russians, but how could they count them if the battlefield was left behind by the Russians, who left it no sooner than they buried all the dead? Let's leave it on the conscience of the chronicler. The only basis on which a conditional victory could be awarded to the enclave is the refusal of the Russians to storm Rakovor and the termination of their campaign. All the other data we have - the flight of most of the Catholic army, huge losses among the Danes, the episcopal army and the Livonian militia, although organized, but still the retreat of the order detachment from the battlefield, which remained behind the Russians, the Dovmont raid - all this testifies to the victory of Russian weapons.

In order to finally put an end to the question of the winner in the Rakovor battle, it is necessary to analyze the events that took place after it. An event of such magnitude could not have had consequences that would not have been noted by the chronicler's pen.

After returning from the Rakovor campaign, the Russian army was disbanded. Dmitry Alexandrovich and the rest of the princes dispersed to their destinies, taking the squads with them. In Novgorod, only the Grand Duke's governor remained - Prince Yuri Andreevich, who had fled from the battlefield. Not a single source mentions any military preparations in Novgorod; complete calm reigned in the Novgorod land.

We observe an absolutely opposite picture in the lands of the Teutonic Order. Already from the beginning of spring, small German raids on the territory controlled by Pskov begin - the Germans rob border villages, take people away "in full". One of these raids ended in a battle on the Miropovna River, during which Prince Dovmont defeated a much larger German detachment. Under the guise of small raids, the Order gathers all possible forces and already at the beginning of the summer of the same 1268 organizes a grandiose campaign against Pskov, motivating it with the need to "avenge" the battle of Rakovor. What kind of revenge can we talk about if, in their own words, the Germans won the battle? For this campaign, the Order is gathering all the forces that it had at that time in the eastern Baltic. According to the testimony of the same chronicler, the author of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, an army of eighteen thousand people was assembled in total, master Otto von Lutherberg himself led the army, who died two years later in the battle on the ice near Karuzen (Karuzin). If internally the Teutons considered themselves victorious at Rakovor, why such a thirst for revenge?

German chroniclers, in order to emphasize the valor and combat skill of the knight brothers, almost always deliberately underestimated the number of their own troops and overestimated the number of enemy troops. It is possible that, speaking about the number of their detachments, the Germans specifically mentioned only the number of cavalry soldiers, "forgetting" to count the militia and auxiliary troops, who, nevertheless, took an active part in the battles. Assessing the number of troops that set off on a campaign against Pskov at the end of May 1268, the Germans themselves name a huge figure for that time - eighteen thousand. Let me remind you that according to the same chronicler in the battle of Rakovor, the German army consisted of only one and a half thousand fighters. These figures, both in the first and in the second case, cannot cause complete confidence, but why such inconsistency - in one case, the number of troops is catastrophically underestimated, and in the other, with some kind of maniacal pride, paint the large number and splendor of the detachments assembled on a campaign? It can be explained by only one thing: the Rakovor company ended in a difficult battle, and the Pskov company ended in a retreat and a truce after several skirmishes and attacks by the Pskovites outside the city walls. The reader of the chronicle should have understood that in the first case, the Germans defeated a huge army with insignificant forces, and in the second, it didn’t even come to a fight, because the Russians were frightened by the Teutonic power. However, first things first.

The defense of Pskov in 1268 deserves a separate description, here it can only be noted that even such a grandiose enterprise did not bring any success to the Order. After a ten-day siege, having heard about the approach of the Novgorod squad, which was not going to help the Pskovites, the Teutons retreated across the Velikaya River and concluded a truce with Prince Yuri, who had arrived to help the Pskovians, "with all the will of Novgorod." Where did the Novgorodians “destroyed” near Rakovor come from in three and a half months such an army, at the approach of which the Teutons (eighteen thousand, by the way!) did not dare to remain on the eastern bank of the Great River and retreated? In February, the Teutons “won victory” near Rakovor over the combined army of Russian princes, and in June, having a much larger army, they did not accept the battle with the forces of only Novgorod and Pskov, which, by the way, near Rakovor, among others, they had just “defeated”. Let's try to explain this contradiction.

According to the Livonian chronicler, Livonian and Latgalian militias were recruited into the order army, some “sailors” were attached (nine thousand, half of the troops where they came from, historians are still guessing), but the “king’s men”, that is, the Danes, as well as knightly detachments and militias from the papal regions (Riga, Yuryev, etc.) as participants in the campaign are not mentioned. Why weren't they there? The answer is simple. Most of the combat-ready men from these regions remained a "corpse" on the field near Makholm near Rakovor, there was simply no one to fight near Pskov. And such a combined composition of the order troops is explained by the fact that everyone who can carry weapons, regardless of their fighting qualities, was recruited into it, just for volume. Two years later, in an attempt to interrupt the Lithuanian raid, at the battle of Karusen, his last battle, Otto von Lutherberg could not recruit even two thousand soldiers, although he was preparing for a serious battle.

It is obvious that the purpose of the march on Pskov was not to achieve any military or political goals, but simply a bluff, a demonstration of "strength", an attempt to convince the Russians that the Order could still oppose them. The Order was not going to fight for real. There was no strength. The low level of combat training of the German troops after the Battle of Rakovor is also evidenced by the successful battles conducted by Dovmont against the Germans in April and June 1268 - on the Miropovna River and near Pskov, where Dovmont inflicted two painful defeats on the crusaders, one during the pursuit of a detachment retreating with booty, the second during a sortie during the siege. At the same time, it should be noted that both in Miropovna and near Pskov, it was precisely the German detachments that had a multiple numerical advantage.

And the last. After the unsuccessful siege of Pskov, a lengthy negotiation process began between Novgorod and representatives of the enclave, as a result of which a peace treaty was signed. The text of this treaty has not been preserved, but the chronicles betray its essence: “And when the Germans heard, they sent envoys with a prayer: “we bow to your will, we retreat all the Norovs, but do not shed blood”; and tacos of Novgorod, guessing, taking the world to all their wills ”(quote from the annals). That is, the representatives of the Catholic enclave, under this agreement, refused further expansion to the east across the Narva River in exchange for the cessation of hostilities. This peace was not broken until 1299.

Let us once again recall the sequence of the main events after the end of the Rakovor campaign: the victory of the Russians in a small battle with a German detachment on Miropovna in April, the German demonstrative campaign against Pskov, which did not pursue any military or political goals, ending with a retreat at the sight of the Novgorod squad (in June), peace negotiations and the conclusion of a peace treaty for "all the will of Novgorod" (February 1269) and a lasting peace. In my opinion, the sequence of these events clearly indicates the lack of opportunities for serious armed resistance among the Germans and Danes after the battle of Rakovor.

Thus, based on the results of the Rakovor battle and the events that followed it, we can confidently state that on the banks of the Pada River on February 18, 1268, the Russian army won a heavy but indisputable victory, which stopped the crusader expansion in the eastern Baltic for more than thirty years.

18 (25 NS) February 1268 near the fortress of Rakvere (the old Russian name is Rakovor or Rakobor, German Wesenburg), a battle took place, called Rakovorskaya in Russian chronicles, and Schlacht bei Wesenberg in German chronicles.

By this time Rakvere fortress, founded by the Danish king Voldemar I, the great-grandson of Vladimir Monomakh, was in the hands of the Livonian Order.

The relationship of the Chud tribes living in these places with the Russians, Danes and Germans developed in completely different ways. In the 11th-12th centuries, both Danish kings and Russian princes were descendants of the Vikings. They speak the same language, are related to each other and impose tribute on the indigenous population of the Baltic and the coast of Lake Peipsi, without encroaching on their way of life, beliefs and customs. The crusader knights of the Livonian, and then the Teutonic Order, behaved differently at all. By the 13th century, after several uprisings, the Chud began to invite small Russian garrisons to help them defend themselves against the Livonians.

The relationship of the Chud tribes living in these places with the Russians, Danes and Germans developed in completely different ways. In the 11th-12th centuries, both Danish kings and Russian princes were descendants of the Vikings. They speak the same language, are related to each other and impose tribute on the indigenous population of the Baltic and the coast of Lake Peipsi, without encroaching on their way of life, beliefs and customs. The crusader knights of the Livonian, and then the Teutonic Order, behaved differently at all. By the 13th century, after several uprisings, the Chud began to invite small Russian garrisons to help them defend themselves against the Livonians.

The Livonians, on the other hand, conclude allied agreements with the new Danish dynasty, which is no longer so closely connected by blood ties with the Russian princes. In 1240 and 1240, the well-known Battle of the Neva and the Battle of the Ice took place. However, this did not stop the aggression of the order.

In 1268, on the initiative Pskov prince Dovmont the Russian army entered the land of Virumaa, which belonged to the allies of the order - the Danes. The Livonian chronicles estimate the strength of the Russians at 30 thousand Pskov warriors, as well as the Novgorodians and the Preyaslav squad of Prince Dmitry Alexandrovich. The allied army approached the walls of the city of Rakvere (Rakovor), where they met with the army of Master Otto von Rodenstein. Under the arm of the German commander was the color of Livonian chivalry - skillful and professional warriors.

The battle took place on 18 February. Apparently, the formations of the opponents were characteristic of the Russian-Livonian wars of the 13th century.

Even from the film about Alexander Nevsky, we know that the knights were built by a "pig". In this case, the chroniclers speak of a "great swine". The organization of the German rati, built in the form of a "pig", can be represented in more detail in the form of a deep column with a triangular crown. A unique document deciphers such a construction - the military manual "Preparing for a Campaign", written in 1477 for one of the Brandenburg commanders. It lists three divisions called gonfalons (Banner). Their type names are "Hound", "Saint George" and "Great"; these banners, respectively, numbered 466, 566 and 666 cavalry soldiers, at the head of each detachment there was a standard bearer and selected knights, located in 5 ranks. In the first rank, depending on the number of banners, from 3 to 7-9 cavalry warriors lined up, in the last from 11 to 17. The total number of wedge warriors ranged from 35 to 65 people. The ranks were lined up in such a way that each subsequent one on its flanks increased by two knights. Thus, the extreme warriors in relation to each other were located, as it were, in a ledge and guarded the one riding in front from one of the sides. This was the tactical feature of the wedge - it was adapted for a concentrated frontal strike and at the same time was difficult to vulnerable from the flanks.

Even from the film about Alexander Nevsky, we know that the knights were built by a "pig". In this case, the chroniclers speak of a "great swine". The organization of the German rati, built in the form of a "pig", can be represented in more detail in the form of a deep column with a triangular crown. A unique document deciphers such a construction - the military manual "Preparing for a Campaign", written in 1477 for one of the Brandenburg commanders. It lists three divisions called gonfalons (Banner). Their type names are "Hound", "Saint George" and "Great"; these banners, respectively, numbered 466, 566 and 666 cavalry soldiers, at the head of each detachment there was a standard bearer and selected knights, located in 5 ranks. In the first rank, depending on the number of banners, from 3 to 7-9 cavalry warriors lined up, in the last from 11 to 17. The total number of wedge warriors ranged from 35 to 65 people. The ranks were lined up in such a way that each subsequent one on its flanks increased by two knights. Thus, the extreme warriors in relation to each other were located, as it were, in a ledge and guarded the one riding in front from one of the sides. This was the tactical feature of the wedge - it was adapted for a concentrated frontal strike and at the same time was difficult to vulnerable from the flanks.

The second part of the gonfalon, according to the "Preparation for the Campaign", consisted of a quadrangular construction, which included bollards. Their number in each of the above detachments was 365, 442 and 629 (or 645), respectively. Among the knechts were servants who were part of the knight's retinue: usually an archer or crossbowman and a squire. All together they formed the lowest military unit - "spear" - numbering 3-5 people, rarely more. During the battle, these warriors, equipped no worse than a knight, came to the aid of their master, changed his horse.

The advantages of the column-wedge-shaped banner included its cohesion, flank cover of the wedge, ramming power of the first strike, and precise controllability. The formation of such a banner was convenient both for movement and for starting a battle. The tightly closed ranks of the head part of the detachment, when in contact with the enemy, did not have to turn around to protect their flanks.

The advantages of the column-wedge-shaped banner included its cohesion, flank cover of the wedge, ramming power of the first strike, and precise controllability. The formation of such a banner was convenient both for movement and for starting a battle. The tightly closed ranks of the head part of the detachment, when in contact with the enemy, did not have to turn around to protect their flanks.

The described system also had disadvantages. During the battle, if it dragged on, the best forces - the knights - could be the first to be put out of action. As for the bollards, during the battle of the knights they were in an expectant-passive state and had little effect on its outcome. If we look at the history of battles involving the knights of the Livonian Order, we will see that almost all of them developed according to the same scenario. The knights crushed the more lightly armed enemy. However, the Battle of Rakovor fully demonstrated the trend that emerged during the battles of Alexander Nevsky. Firstly, Rus' was able to field heavily armed and ready to fight warriors. Secondly, by this time, Russian warriors, thanks to contacts with the steppes, had mastered the skills of equestrian combat, which the Vikings, who were forced to cede the Baltic coast to the Germans, did not possess. Thirdly, the troops of the Livonian and Teutonic orders never had a high morale, therefore, they could not hold the line. (By the way, this also manifested itself in the battles of the order in Cilician Armenia, the population of which the knights undertook to protect from the Turks and could not do this).

The Germans and Danes lined up in a wedge and attacked the center of the allied princes' troops, where the pawns stood - mainly from the Novgorod militia. The fight here was fierce. The illustrious Iron Regiment (by the way, the elite tank units of the Third Reich were also called in the 20th century) of the knights attacked the center of the Russian army, but the Russian militias surprised the knights by managing to hold back their first onslaught and imposing a hand-to-hand fight on them, in which the Russians had no equal throughout military history. During the battle, the knights suffered heavy losses, but the Russians also lost many soldiers. The head of the Novgorod militia, the posadnik Mikhail, also died.

The Germans and Danes lined up in a wedge and attacked the center of the allied princes' troops, where the pawns stood - mainly from the Novgorod militia. The fight here was fierce. The illustrious Iron Regiment (by the way, the elite tank units of the Third Reich were also called in the 20th century) of the knights attacked the center of the Russian army, but the Russian militias surprised the knights by managing to hold back their first onslaught and imposing a hand-to-hand fight on them, in which the Russians had no equal throughout military history. During the battle, the knights suffered heavy losses, but the Russians also lost many soldiers. The head of the Novgorod militia, the posadnik Mikhail, also died.

Seeing his losses, Otto von Rodenstein began to retreat. He believed that in this way he would save the knights of the Order from death in hand-to-hand combat, but he did not take into account that a heavy cavalryman turns around with great difficulty and cannot quickly retreat. Only lightly armed horsemen who stood in the back rows, as well as crossbowmen and squires, could turn around. The princely cavalry, which had been in ambush until that moment, attacked the Livonians on the flank, finished off the knights and chased the retreating. The Russians drove the Livonians for seven versts. Only a few of them managed to escape. In the evening, another German detachment approached the battlefield, attacked the convoy, but did not enter the battle and retreated by morning, content with the looted belongings.

The Order suffered the worst defeat since the Battle of the Ice. The Iron Regiment ceased to exist. All heavily armed knights who failed to turn around and retreat either died in hand-to-hand combat or were taken prisoner. However, according to the Rhymed Chronicle (the German chronicle of that time), practically no one was left alive. In this battle, the Russian squad showed its combat capability against a heavily armed enemy. However, the Russians also suffered huge losses in this battle. The fact is that, despite the significant numerical superiority at the beginning of the battle, the Russians were less professional and lighter armed. At the same time, after the Battle of Rakovor, the princes repeatedly successfully used the Novgorod militia against various opponents.

The Order suffered the worst defeat since the Battle of the Ice. The Iron Regiment ceased to exist. All heavily armed knights who failed to turn around and retreat either died in hand-to-hand combat or were taken prisoner. However, according to the Rhymed Chronicle (the German chronicle of that time), practically no one was left alive. In this battle, the Russian squad showed its combat capability against a heavily armed enemy. However, the Russians also suffered huge losses in this battle. The fact is that, despite the significant numerical superiority at the beginning of the battle, the Russians were less professional and lighter armed. At the same time, after the Battle of Rakovor, the princes repeatedly successfully used the Novgorod militia against various opponents.

Thanks to the threat of heavily armed knights from the West and lightly armed steppes from the East, the Russian army by the late Middle Ages was one of the most combat-ready and mobile and could fight any enemy in any climatic and weather conditions.

Thanks to the threat of heavily armed knights from the West and lightly armed steppes from the East, the Russian army by the late Middle Ages was one of the most combat-ready and mobile and could fight any enemy in any climatic and weather conditions.

The Novgorod army and the squad of Dmitry Alexandrovich stood under the walls of Rakovor for three days. They did not dare to storm the city. At this time, the Pskov squad of Dovmont marched through Livonia with fire and sword, looting and capturing prisoners. The prince took revenge on the enemy for attacks on his lands. The battle of Rakovor stopped the movement of the Livonians to the northeast for 30 years. The Livonian Order could no longer seriously threaten the powerful principalities of Northwestern Rus'.