Lectures on medieval philosophy. Issue 1. Medieval Christian Philosophy of the West Sweeney Michael

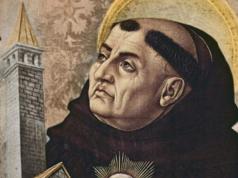

LECTURE 14 Thomas Aquinas on universals: the influence of Aristotle

Thomas Aquinas on universals: the influence of Aristotle

Three different approaches can be proposed to consider how Aristotle's moderate realism was received and critically revised by Thomas Aquinas. The first is to demonstrate in detail what Thomas accepts and what he rejects in Aristotle's understanding of universals. This will require comparing Aristotle's Organon, On the Soul and Metaphysics with the commentaries and original writings of Thomas. Obviously, such a task cannot be accomplished within the framework of one lecture. Second, we might begin by considering Aquinas's own epistemological critique of ultrarealism. The best examples of such criticism are questions 5 and 6 of his commentary on Boethius' On the Trinity. Here, in the discussion of division and the methods of the sciences, there is an analysis of abstraction that quickly goes beyond the Aristotelian critique of Platonic forms. However, this approach excludes a more general perspective that also allows us to consider anthropology and cosmology. Therefore, the approach to be taken here will be to consider Thomas's treatment of universals in connection with the new attitude to the world discussed above, expressed in the appeal to Aristotle's natural philosophy, in the development of universities and mendicant orders. The most appropriate text for this is ST 1.84–85. As Aquinas states in the prologue, the Summa Theologica is a condensed and ordered exposition of theology, that is, a primer, the main property of which is simplicity. This somewhat simplified generalized approach meets our goals.

ST 1.84.4 begins by outlining the main tenets of ultrarealism attributed to Plato. For Abelard, the main dogma of ultra-realism was the assertion that universals are substances. Showing a better understanding of metaphysics and an ability to solve the problems associated with it, made possible by the translations of the Neoplatonists, Aristotle, Muslim and Jewish philosophers, Aquinas considers the idea that form is separate from matter to be the most adequate expression of ultra-realism. For the ultra-realist, individual forms constitute the causes of both being and human knowledge; Therefore, the question of universals relates as much to metaphysics as to epistemology. Thomas's attention is focused on both Avicenna and Plato: he tries to demonstrate the similarities and differences in the positions of both on the question of universals. Avicenna contradicts Plato in that, in his opinion, forms do not exist independently as substances, and knowledge of them is not innate to the human mind. Avicenna agreed with Plato that forms exist prior to their presence in the human mind and in sensible things. Avicenna combines the positions of Plato and Aristotle by placing the forms in the active intellect, which is primarily responsible for their emanation into the human mind and into sensible things. Therefore, Thomas shares Averroes' desire to distinguish between the positions of Aristotle and Avicenna. No matter how faithful a follower of Aristotle Avicenna may seem, Thomas still notes that his interpretation of universals is closer to Plato than to Aristotle.

Thomas's critique of ultra-realism is very different from that undertaken by Abelard, who tried to show the logical inconsistency of the ultra-realist position. Thomas's argument is not intended to demonstrate through logic the internal contradictions of ultra-realism; The main objection is that ultrarealism is not capable of presenting a consistent doctrine of man. He cannot explain why the human intellect feels the need for union with the body, while the object of knowledge is form, separated from matter. If we answer this that the soul is united with the body for the good of the body, that is, the soul controls the body for the sake of the body itself, just as a philosopher rules people for their good, such an answer will not be satisfactory, since in this case the union of body and soul is impossible considered natural. In other words, the soul is not naturally inclined to unite with the body, only the body by nature is inclined to unite with the soul. Such a union is essentially necessary, and therefore natural, only for the body. Initially, Augustine made an attempt to connect the Fall described in the book of Genesis with Plato's explanation of the union of the soul with the body as the fall of the soul, leaving a purely immaterial mode of existence. In the 3rd book of De libero arbitrio, Augustine expresses doubts about the identity of these two falls, but he still does not give a definite explanation of the reasons for the union of soul and body. Thomas argues that the main error of ultra-realism is not logical or epistemological, but concerns anthropology, since this position recognizes the union of soul and body as unnatural, but does not provide an acceptable explanation for the reasons for such an unnatural union.

The best that ultrarealism can say about the body is that the body is the accidental cause of knowledge. Sense experience may serve to remind the soul of its knowledge of forms separated from matter, but the senses themselves are not the causes of knowledge. If feelings are not something essential for knowledge, then the body is not essential for the soul. In the bodily mode of existence of the soul, feelings can contribute to its return to knowledge, but it is more likely that they will become an obstacle to knowledge. In any case, feelings do not turn out to be necessary causes, and therefore the body is in no way necessary in ultra-realist epistemology.

Unlike Abelard, Thomas is ready to recognize the logical and epistemological consistency of the position of ultra-realism. His objections boil down to the fact that ultrarealism does not provide an explanation of the human being in its entirety, that is, it does not explain why a person has a body. Hence the appeal to Aristotle and his idea of the natural union of soul and body as a means of explaining the presence of intellectual souls in matter. What attracts Thomas to Aristotle is his ability to explain why man is present in the world and to show that man belongs to the world. This turn from ultra-realism reflected dissatisfaction with the idea that the material world is not the natural place of human beings. A person cannot and should not run away from the world - material, political, the world in any sense with the exception of the sinful world - since man is naturally connected with the world. From this point of view, the monastery appears to be an unnatural and unusual place of residence, intended for those few who have the appropriate vocation; the university is a more natural place, corresponding to the nature of the human mind. The philosophy of Aristotle is not perceived by Thomas as a holistic teaching, as it was for Averroes; rather, it is used as the basis for the formation of a philosophy whose fundamental principle will be the naturalness of the human body. The challenge facing such a philosophy is how to postulate that the world is man's home without forgetting that our ultimate goal lies beyond this world, as Augustinian ultra-realism and the monastic tradition constantly remind us.

In ST 1.84.6, Thomas describes from historical perspective how Aristotle's approach to universals makes possible a more holistic view of man and his knowledge compared to the teachings of Aristotle's predecessors. Thomas identifies three main interpretations of universals. The first is represented by Democritus and those Pre-Socratics who made no distinction between the senses and the intellect. They recognized only one cognitive act - sensation and one cognitive object - individual things. Since the pre-Socratics of the materialist direction do not recognize any objects of knowledge other than individual objects, their position is basically identical to the nominalist one. Plato's rejection of this position marked the beginning of the emergence of ultra-realism, for which feelings and intellect are not only different, but also separated. In addition, the senses and the intellect are separated in such a way that there is only one act of cognition - the intellectual and one object of cognition - the universal: the sensory and the individual are not objects of cognition. According to Thomas, Aristotle's answer is as follows: he agrees with Plato that the Pre-Socratics were unable to explain knowledge by reducing it to sensation; at the same time, he does not support the amendment introduced by Plato - to identify cognition with the intellectual act. Both Democritus and Plato, in their versions of the theory of knowledge, miss some aspects of knowledge: Democritus eliminates intellectual, and Plato eliminates sensory phenomena. Human cognition in its entirety can be explained if sensation and intellectual act are distinct but not separate. Aristotle pays tribute to both Democritus, recognizing that knowledge begins with sensation, and Plato, arguing that intellectual knowledge goes beyond sensations. In this way, balance is restored and all aspects of cognition are taken into account. Plato's ascent to knowledge through recollection is a return to actuality (the intelligible) already present in the soul. Aristotelian abstraction is an ascent to a new actuality (the intelligible), which was not present in the soul, but was implicitly or potentially contained in sensible objects. Thus, Aristotle combines the new knowledge acquired in the act of sensation according to the epistemology of Democritus with the Platonic idea that the intelligible already exists in the mind. The difference in Aristotle's position is that the intelligible pre-exists in the sensible, whereas, according to Plato, it pre-exists in the intellect. Aristotle replaces Platonic recollection with abstraction, while asserting the need for ascent - ascent from one act of cognition (sensation) to another (intellectual act). Let us recall that Plato's ascent is carried out from ignorance (sensation and forgetting of the material world) to knowledge (intellectual acts and remembering). A holistic idea of human cognition becomes possible if we, together with Democritus, recognize that sensation is a necessary cause of cognition, and complement this with Plato’s intuition of the irreducibility of cognition to sensation.

Although Plato correctly postulates form as the object of intellectual knowledge, it is through matter that form has an individual existence in sensible substances. Sensation gives us access to what the form contains, but the senses are not able to grasp the form itself, that is, the form as a universal. Abstraction is the separation of form from the particulars of its material existence that make a thing special and unique. We are immediately faced with a dilemma if we maintain that the actuality of the intellect is something new because it distinguishes form from external sensible objects, and at the same time we hold that the intellect comprehends form by separating intelligible objects from the sensible. For from the first it follows that the intellect is naturally in a potential state, since its object is external, and from the second it follows that the intellect is in a state of actuality, since it acts on the sensible, raising it to the level of the intelligible. As a solution, it is proposed to distinguish potential and active intelligences or intellectual properties. Aristotle's lack of clarity about the relationship of the potential and active intellect with the soul as a form gave rise to three different interpretations: for Avicenna, the active intellect is separated from the individual soul, as we know from ST 1.84.4; for Averroes both intellects are separated from the soul; for Thomas, both are properties of the individual human soul.

This consideration of Thomas's treatment of Aristotle's doctrine of abstraction gives a fairly clear idea of his differences with Abelard. Recall that Abelard's attempt to formulate an intermediate position between ultra-realism and nominalism was hindered by limited access to, and perhaps limited interest in, Aristotelian writings beyond the Organon. Therefore, Abelard's explanation of “status” is limited to the fact that the similarity between individual substances underlies the natural meaning of universals. Thomas, drawing on Aristotle, can say that form, not substance, is the element common to many individuals, determining their belonging to the same species and underlying the natural meanings of universals. Moreover, Abelard describes the result of abstraction as a vague image of a number of separate substances, which is more consistent with nominalism, and ultimately with the materialism of the Presocratics, than with realism. From this point of view, Abelard’s idea of abstraction does not notice the difference between feeling and intellect for fear of falling into the mistake of Plato, who separated them and denied the need for a sensory cause of knowledge. Thanks to the Aristotelian concept of form, Thomas manages to establish that in abstraction form is conceived separately from the material particulars that individualize it: abstraction is the obtaining not of a vague image, but of a clear understanding of the universal, unchanging and necessary element of material things - form, and sensation is the grasping of particular, changing and random elements in material things - matter as the principle of individuation.

Much as Thomas owes to Aristotle in forging a path between nominalism and ultra-realism, it would be wrong to conclude that he simply repeated Aristotle and made no significant changes to his teaching. As can be seen from Thomas's discussion of these same issues in Quaestiones de anima 15, the immediate target of his criticism in ST 1.84.7 is Avicenna, although the criticism is implicitly directed at Aristotle. Avicenna argues that a sensory object or image is necessary for the acquisition of intellectual knowledge, but not for operating with already acquired knowledge. If this were so, Thomas objects, then upon acquiring knowledge of the sciences the body would no longer be necessary. And since the brain is a bodily organ that carries out the work of imagination, it would be necessary only at the first stages of the cognitive act for the formation of an image (phantasm), from which the intelligible is abstracted, but would no longer be required for further cognition. However, this clearly contradicts experience, because when a person who has knowledge experiences disruptions in the functioning of the brain due to injury or old age, he cannot fully operate with this knowledge. Thomas points out another fact that supports his statement: we are not able to think without resorting to imagination. Our own experience shows that man is unable to get rid of imagination and is unable to know incorporeally. We are embodied intellects, but embodied not for the sake of the body, but for the sake of the intellect, dependent in its activity - in the acquisition and use of intellectual knowledge - on the senses and the brain.

Thomas does not contradict Plato and Avicenna that the intellect goes beyond the imagination, but he denies that we can think without recourse to the imagination. Avicenna is a Platonist in the sense that he recognizes our need for the imagination and the body only for the acquisition of knowledge, while the acquisition of knowledge is understood as a gradual detachment from the body. Both Avicenna and Plato view philosophical life as an ascent that should not be accompanied by any descent: the ascent to form and to the intelligible does not require a return to matter and the sensible. Thus, recognizing our dependence on the material world as the starting point of knowledge, Avicenna, together with Plato, faces the problem of explaining why the philosopher returns to the material, sensory world after ascending to form. Thomas's appeal to Aristotle in sed contra ST 1.84.7 does not hide the fact that this doctrine of "conversio ad fantasmata", or the idea of the necessity of using the imagination in the process of knowledge, is not contained in Aristotle's writings, at least not in an explicit form. Indeed, the gradual detachment from the body and imagination, postulated by Avicenna, is in good agreement with what is said in Aristotle’s treatise “On the Soul”. According to Thomas, the response of moderate realism to Plato, as well as the necessity of descent for the philosopher, will not be understood unless we recognize the constant need of the intellect for imagination. For Plato and Avicenna, as well as for Aristotle, by default, after form is achieved, the descent into the material and sensory seems unnatural. For Thomas, the descent is necessary and natural: no coercion is required. Thus, Thomas argues that the idea of cognition put forward by moderate realism will be complete only if both ascent and descent are recognized as necessary moments in every act of cognition.

It is not surprising, then, that Thomas affirms the compatibility of the life of contemplation and the life of action. Indeed, from the point of view of Thomas, the unity of contemplation and action is as natural as the unity of cognitive ascent and descent. If the descent is as natural as the ascent, then there is no need to run away from the material world or participation in the life of the city and its affairs, and then the teaching activity of a philosopher is natural and normal. Recognizing both ascension and descent as natural brings clarity to the question of the nature of the union of the soul with the body - this union exists for the sake of the soul, and not for the sake of the body. In other words, we are again faced with the fact that the question of universals is inseparable from anthropological problems. The fundamental principle of Thomas's philosophy, which reflects this union of epistemology and anthropology, states: the level of being of the knower corresponds to the level of being of the object of his knowledge. Corresponding to the intellectual being associated with matter - man - is the knowledge of the form that exists in matter. Corresponding to an intellectual being separated from matter - an angel - is the knowledge of a form that exists separately from matter. Aristotelianism becomes practically indistinguishable from Platonism if the object of human knowledge is identified with the object of intellect. If the object of cognition is considered to be a form isolated by abstraction in the process of cognition, then we have the gradual separation of soul from matter, defended by Avicenna. However, Thomas emphasizes that the object of knowledge is a form that exists outside the intellect, that is, existing in matter; form receives immaterial existence only in the intellect through abstraction. But then one cannot stop at the abstraction of form from matter: knowledge of form as a universal must be supplemented by knowledge of the universal outside the intellect - in its particular existence in matter. Both ascent and descent are natural, and then the union of soul and body is natural, since there is only one object of knowledge - the form existing in matter, partly grasped by the senses, partly comprehended by the intellect. But if form is inseparable from matter outside the mind, then the intellect cannot in any way renounce the body or the imagination.

Thomas's integration of epistemology and anthropology seems most successful when he draws a parallel between moderate realism - as an intermediate position between ultra-realism and nominalism - and the intermediate position of man between angels and animals. Thomas expands the series of types of knowers to three, adding animals to it - a gradation corresponding only to the individualized, i.e., material state of the form, and not to the state of the form as form itself. Then it turns out that animals know, but only through sensory and not intellectual knowledge. Democritus and the nominalists were mistaken in attributing to man what is characteristic of animals and refusing to explain cognitive phenomena that go beyond animal properties, that is, the ability of human thinking to transcend the boundaries of particular conditions of time and space. The other extreme is the mistake of Plato and the ultra-realists - to attribute to man what is characteristic of an angel. Both versions of anthropology lose sight of the uniqueness of human nature. Thomas believes that his moderately realistic interpretation of universals is confirmed by considering the act of human cognition, meaning the dependence of human cognition on the brain. He also believes that only moderate realism can justify a "middle" or intermediate position of man between animals and angels. Human nature, he argues, is more complex than animal or angelic, but there is always a temptation to simplify it, reducing it to one of the extremes. The same temptation was reflected in the debate about universals.

The consequence of this intermediate position of man and human knowledge is that direct knowledge of the immaterial is inaccessible to man. All human knowledge of the immaterial and intelligible is carried out through the knowledge of the material and sensory. In contrast to Augustine's ultra-realism, Thomas denies the possibility of direct knowledge of God: the only natural path to God lies through the material world. In our natural knowledge of God, we are dependent on involvement in the material world, which we are not allowed to outgrow by natural means. Thus, it is obvious how suitable such a philosophy is for a university, just as Augustine's philosophy was optimal for a monastery. If we use terminology that expresses the difference between the approaches to political philosophy of Augustine and Thomas, then for both Augustine and Thomas, man is a pilgrim on a journey that has no end in this world. For Thomas, we are also citizens who by nature belong to this world. The uniqueness of man's position in space exactly corresponds to his rootedness in the world, while his belonging to this world in no way diminishes his uniqueness.

This text is an introductory fragment. From the book History of Western Philosophy by Russell BertrandChapter XIII. NE. THOMAS AQUINAS Thomas Aquinas (born in 1225 or 1226, died in 1274) is considered the greatest representative of scholastic philosophy. In all Catholic educational institutions in which the teaching of philosophy has been introduced, the system of St. Thomas is prescribed to be taught as

From the book Thomas Aquinas in 90 minutes by Strathern PaulThomas Aquinas in 90 minutes translation from English. S. Zubkova

From the book Man: Thinkers of the past and present about his life, death and immortality. The ancient world - the era of Enlightenment. author Gurevich Pavel SemenovichThomas Aquinas Summa of TheologyPart I. Question 76. Article 4: Is there another form in man besides the thinking soul? Thus we come to the fourth article. There seems to be another form in man besides the thinking soul.1. For the Philosopher speaks in Book II. "ABOUT

From the book Lovers of Wisdom [What a modern person should know about the history of philosophical thought] author Gusev Dmitry AlekseevichThomas Aquinas. The harmony of faith and knowledge of Scholasticism as an attempt to synthesize faith and reason, religion and philosophy reached its peak in the teachings of the Italian religious philosopher Thomas Aquinas. Religious faith and philosophical knowledge do not contradict each other, he says,

From the book History of Philosophy in Brief author Team of authorsALBERT THE GREAT AND THOMAS AQUINAS Gradually it became clear that Augustinianism was not able to withstand the powerful influence of Aristotelianism. It was necessary to harness Aristotelian philosophy in order to eliminate the constant danger of deviation from Catholic orthodoxy.

From the book History of Philosophy author Skirbekk GunnarThomas Aquinas - Harmony and Synthesis Medieval philosophy, often called scholasticism (philosophy that is “studied in school”, in Greek schole), is divided into three periods: 1) Early scholasticism, which is usually dated from the 400s. until the 1200s In many ways this

From the book History of Medieval Philosophy author Copleston Frederick From the book Introduction to Philosophy author Frolov Ivan5. Thomas Aquinas - systematizer of medieval scholasticism One of the most prominent representatives of mature scholasticism was the monk of the Dominican Order Thomas Aquinas (1225/1226–1274), a student of the famous medieval theologian, philosopher and natural scientist Albert

From the book Lectures on the history of philosophy. Book three author Hegel Georg Wilhelm Friedrichb) Thomas Aquinas Another, as famous as Peter Lombard, was Thomas Aquinas, who came from a Neapolitan count family and was born in 1224 in Rocassique, in the family castle. He joined the Dominican Order and died in 1274 during a trip to the Lyon church

From the book Lectures on Medieval Philosophy. Issue 1. Medieval Christian philosophy of the West by Sweeney MichaelLECTURE 15 Thomas Aquinas on universals. Avicenna on the problem of being Augustine and his medieval followers tried to build their philosophy on the basis of identifying God with being for at least two reasons. First, they sought to bring their philosophy into

From the book Philosophy author Spirkin Alexander GeorgievichLECTURE 16 Thomas Aquinas on the freedom and omnipotence of God. Controversy with Avicenna and Peter Damiani One of the main objections to Thomas, who tried to build an ontology based on the difference between existence and non-existence, is formulated as follows: if God

From the book 50 golden ideas in philosophy author Ogarev GeorgyLECTURE 17 Thomas on Universals: Divine Ideas For Augustine, Platonic ideas become divine ideas for two reasons. One of the reasons, as we saw in Augustine’s work “Eighty-three Questions,” is of a metaphysical nature: the identification of Plato’s

From the book Philosophy of Law. Textbook for universities author Nersesyants Vladik Sumbatovich4. Thomas Aquinas Thomas Aquinas (1225 or 1226–1274) is the central figure of medieval philosophy of the late period, an outstanding philosopher and theologian, systematizer of orthodox scholasticism, founder of one of its two dominant directions - Thomism. Heritage

From the book Popular Philosophy. Tutorial author Gusev Dmitry Alekseevich10) “PROVING THE EXISTENCE OF GOD” (THOMAS AQUINSKY) The great medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas, in one of his works, attempted to prove the existence of the Divine, based on the capabilities of the human mind. It is known that God is an old subject

From the author's book1. Thomas Aquinas From the standpoint of Christian theology, the original philosophical and legal concept was developed by Thomas Aquinas (1226-1274), the largest authority in medieval Catholic theology and scholasticism, with whose name an influential history is associated

From the author's book5. Angelic Doctor (Thomas Aquinas) The most outstanding philosopher of the heyday of scholasticism and the entire Middle Ages in general was the Italian religious thinker Thomas Aquinas. In Latin, his name sounds like Thomas, so his teaching was called Thomism. IN

Thomas(1226-1274) was born in Aquino in Sicily. He came from shchi, if he sees in her a force that embodies in earthly life the idea of a just family, but he preferred a military career to the path of a monk and theology. Augustine believes that it is the state that is capable of implementing on the. After studying at a Dominican monastery Thomas continued to teach the principle of Christian justice in the earthly life of man, his education at the University of Naples, and then taught philosophy “Everyone will be rewarded according to his deeds.” The condition for this is submission And theology at the universities of Naples, Rome, Paris and Cologne, the state of the divine will as the source of justice and law. IN history of Christian philosophy and theology Thomas entered as a pro- From the righteous Abel is happening "Christian state" founded- ]debtor of the rational line begun Augustine. It is known as sonoe on the postulates "City of God" i.e., on the care of rulers for their subjects, the creator scholastics(rational or "school" knowledge) at its most From a sinner Caina is happening "society of the wicked" based on the perfect version, for which he was awarded the title of postulates by the Catholic Church "City of the earth" i.e., on violence and robbery. nia"angelic doctor" After death Thomas scholasticism is degenerating, losing its meaning as a school of rational-logical thinking and acquiring the modern meaning of dead knowledge.

Special success Thomas reached in reception(borrowing) ancient philosophy in Christian theology. His views were particularly influenced by Aristotle.

In his treatises "Summa Theologica", "Summa Against the Pagans" And "On the Rule of Sovereigns"Thomas used provisions compatible with Christianity, And thereby significantly improving the concept Aristotle.

Thomas, like Aristotle, understood a person as "social being" which is guided in its behavior by reason. Famous formula Aquinas"science is the handmaiden of theology" determines the interaction of religious faith and rational knowledge in a person’s knowledge of the world around him. Thomas considers science to be the lowest type of knowledge, since it is based on feelings and can only comprehend the external, material world that is not very important for humans, while theology is the highest type of knowledge, because it is based on reason and faith. Only theology can give a person knowledge of the basic laws of existence and the meaning of life and thereby lead to the salvation of the soul.

Compared to Augustine Thomas deepens the rationalism of his theology and moves from voluntaristic To intellectual ethics. Generally ethical positions Augustine And Thomas are the same: a person must be guided in his actions by the Ten Commandments Sermon on the MountChrist. But Thomas supplements these commandments with logical argumentation Aristotle. A person’s acquisition of knowledge must precede his desires, that is, knowledge must dominate over virtue. A person should focus not on mechanically memorized, but on thoughtful and consciously fulfilled commandments.

However, in contrast to Aristotle Thomas distinguishes a person as a Christian, correlated only with God, and as a citizen, correlated, as part of him, with the state.

Thomas proceeded from Aristotle's understanding of the state as part of the world order. But if for Aristotle the state is a part of physical nature, then for Thomas it is a part of the universal world order created and governed by God, as a form of cooperation between people united by political authorities that have the right to issue laws.

The purpose and meaning of the existence of the state, according to Thomas, are to ensure the material means of existence of individuals, to create conditions for their mental and moral development. Thomas, based on the concept of natural human rights Aristotle, justifies the right to own private property by emphasizing that the state must guarantee this right.

After Augustine Thomas. creates an authoritarian political and legal concept. They both assume that the vast majority of people are prone to sin and therefore need government guidance. They both deny the basic tenet of medieval heresies about the equality of people.

Thomas identifies the processes of the creation of a state by people and the creation of the world by God: first, a mass of people/things arises, and then they are divided into types/classes in accordance with their functions. Authoritarianism of the political and legal concept Thomas based on teaching Aristotle about "active form"(God), in an authoritarian form giving life, movement and development "passive matter"(i.e. nature and humanity).

The state in its hierarchical structure should be divided into three estates (categories of workers): the clergy, the nobility and those engaged in material production. The participation of all classes in government is a guarantor of social peace and order. Class “The status of an individual is determined by God by birth, and a person cannot change it by his own will. Social doctrine Thomas static, like the divine world order.

Thomas after Aristotle distinguishes between just and unjust forms of government as kingdoms (political monarchies) and despotisms (absolute monarchies), but at the same time Thomas changes the concept of the common good as a criterion for distinguishing states, bringing it into line with Christian doctrine.

IN Unlike Aristotle Thomas considers the optimal form of state not a republic (polity), but a monarchy. Aquinas prefers the unity of the state to diversity as the basis of internal peace and a means of preventing discord.

~ Thomas understands power in three forms: as an essence (divine institution), as an acquisition (the form of the state) and as a use (the mode of functioning of the state).

Power as an entity is a God-defined, eternal, and inviolable principle of the world order, embodied in relations of domination And submission.

The power of one king can be replaced by the power of another, but power cannot be destroyed as an entity, because this will destroy both the entire world order and the state itself. This is unacceptable, because it will return society to a primitive state of chaos and violence.

Power as acquisition and use can be exercised not only according to divine, but also according to human laws. At these levels, abuses of rulers, violations by them and divine, And natural laws. If the king, in governing the state, is guided by personal good and arbitrariness, then the church defines him as a sinner, and he loses the right to power, and, therefore, his subjects have the right to overthrow the sinful ruler. Legally, this is carried out through the intervention of the Pope, who excommunicates such a ruler from the church. Only the religious and moral influence of the church on secular rulers is a guarantee against their degeneration into tyrants and, therefore, legitimizes their power. Thus, Thomas substantiates the pope's theocratic claims as "Head of the Republic of Christ" to pan-European power.

IN comparison with Aristotle Thomas increases the degree of freedom of the individual, since the individual’s free will functions at various levels of existence, both on the natural and on the divine-sacral. The individual's free will is based on knowledge of the divine goals of existence and, accordingly, this freedom is limited and structured by the laws of this existence.

Law Thomas understands how:

the rule for achieving God's purposes;

reasonably perceived necessity;

expression of the divine mind.

Thomas borrows from Aristotle the difference between natural (natural) and positive (human) law, but complements these two types with their sacred projections.

Under natural law Thomas understands the totality of the laws of movement of all beings towards goals determined by their nature, and, accordingly, regulating the order of human coexistence, self-preservation and procreation.

It is complemented by human laws as effective law, reinforcing natural law with state coercion. This coercion limits the perversions of man's free will, which manifest themselves in his ability to do evil.

Natural law, as a reflection of the divine mind in the human mind, corresponds to eternal law, as "the divine mind that governs the world."

Since human law cannot independently put an end to evil in the world, its projection comes to its aid - the divine or revealed law expressed in the text of Holy Scripture. The authority of the Bible overcomes the imperfection of the human mind, helping it achieve unity in its understanding of truth and ensuring the unity and harmony of the structure of the state and society.

Thus, Thomas Aquinas managed to organically combine the achievements of ancient and Christian political and legal thought, creating the basic medieval concept of state, church and law.

On January 28, Catholics celebrate the Feast of St. Thomas Aquinas, or, as we used to call him, Thomas Aquinas. His works, which combined Christian doctrines with the philosophy of Aristotle, were recognized by the church as one of the most substantiated and proven. Their author was considered the most religious of the philosophers of that period. He was the patron of Roman Catholic colleges and schools, universities and academies, and of theologians and apologists themselves. A custom has still been preserved, according to which schoolchildren and students pray to the patron saint Thomas Aquinas before taking exams. By the way, the scientist was nicknamed the “Angel Doctor” because of his “power of thoughts.”

Biography: birth and studies

Saint Thomas Aquinas was born in the last days of January 1225 in the Italian city of Aquina into a family of aristocrats. From early childhood, the boy liked communicating with the Franciscan monks, so to receive his primary education, his parents sent him to a monastery school, but then they really regretted it, since the young man really liked the monastic life and did not at all like the way of life of the Italian aristocrats. Then he went to study at the University of Naples, and from there he was going to Cologne to enter the faculty of theology at the local university.

Difficulties on the way to becoming

Thomas's brothers also did not like that their brother would become a monk, and they began to hold him hostage in their father's palace so that he could not become a servant of the Lord. After two years of seclusion, he managed to escape to Cologne, and then his dream was to study at the famous Sorbonne at the Faculty of Theology. When he turned 19, he took a vow and became one of them. After that, he went to Paris to fulfill his long-time dream. In the student environment of the French capital, the young Italian felt very constrained and was always silent, for which his classmates nicknamed him “the Italian bull.” Nevertheless, he shared his views with some of them, and already during this period it was obvious that Thomas Aquinas was speaking as a representative of scholasticism.

Further successes

After studying at the Sorbonne, having received academic degrees, he was assigned to the Dominican monastery of Saint-Jacques, where he was supposed to conduct classes with novices. However, Thomas received a letter from Louis the Ninth himself, the French king, who urged him to return to court and take the position of his personal secretary. Without hesitating for a moment, he went to the court. It was during this period that he began to study the doctrine, which was later called the scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas.

Some time later, a General Council was convened in the city of Lyon with the goal of uniting the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches. By order of Louis, France was to be represented by Thomas Aquinas. Having received instructions from the king, the philosopher-monk headed to Lyon, but he never managed to get there, since on the way he fell ill and was sent for treatment to the Cistercian Abbey near Rome.

It was within the walls of this abbey that the great scientist of his time, the luminary of medieval scholasticism, Thomas Aquinas died. He was later canonized. The works of Thomas Aquinas became the property of the Catholic Church, as well as the religious order of the Dominicans. His relics were transported to a monastery in the French city of Toulouse and are kept there.

Legends of Thomas Aquinas

History has preserved various stories related to this saint. According to one of them, one day in the monastery at mealtime Thomas heard a voice from above, which told him that where he was now, that is, in the monastery, everyone was full, but in Italy the followers of Jesus were starving. This was a sign to him that he should go to Rome. He did just that.

Belt of Thomas Aquinas

According to other accounts, Thomas Aquinas's family did not want their son and brother to become Dominican. And then his brothers decided to deprive him of chastity and for this purpose they wanted to commit meanness, they called a prostitute to seduce him. However, they failed to seduce him: he snatched a coal from the stove and, threatening it, drove the harlot out of the house. It is said that before this, Thomas had a dream in which an angel girded him with a belt of eternal chastity given by God. By the way, this belt is still kept today in the monastery complex of Scieri in the city of Piedmont. There is also a legend according to which the Lord asks Thomas how to reward him for his loyalty, and he answers him: “Only with You, Lord!”

Philosophical views of Thomas Aquinas

The main principle of his teaching is the harmony of reason and faith. For many years, the scientist-philosopher searched for evidence that God exists. He also prepared responses to objections to religious truths. His teaching was recognized by Catholicism as “the only true and true.” Thomas Aquinas was a representative of the theory of scholasticism. However, before moving on to the analysis of his teaching, let's understand what scholasticism is. What is it, when did it arise and who are its followers?

What is scholasticism

This is a religious philosophy that originated in and combines theological and logical postulates. The term itself, translated from Greek, means “school”, “scholar”. The dogmas of scholasticism formed the basis of teaching in schools and universities of that time. The purpose of this teaching was to explain religious views through theoretical conclusions. At times these attempts resembled a kind of explosion of groundless efforts of logic for the sake of fruitless reasoning. As a result, the authoritative dogmas of scholasticism were nothing more than stable truths from the Holy Scriptures, namely, the postulates of revelation.

Judging by its basis, scholasticism was a formal teaching, which consisted of the propagation of high-flown reasoning that was incompatible with practice and life. And so the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas was considered the pinnacle of scholasticism. Why? Yes, because his teaching was the most mature among all similar ones.

Five Proofs of God by Thomas Aquinas

According to the theory of this great philosopher, one of the proofs of the existence of God is movement. Everything that moves today was once set in motion by someone or something. Thomas believed that the root cause of all movement is God, and this is the first proof of its existence.

He considered the second proof that none of the currently existing living organisms can produce themselves, which means that initially everything was produced by someone, that is, by God.

The third proof is necessity. According to Thomas Aquinas, every thing has the possibility of both its real and potential existence. If we assume that all things without exception are in potential, then this will mean that nothing has arisen, because in order to move from potential to actual, something or someone must contribute to this, and this is God.

The fourth proof is the presence of degrees of being. When talking about different degrees of perfection, people compare God with the most perfect. After all, only God is the most beautiful, the most noble, the most perfect. There are not and cannot be such people among people; everyone has some kind of flaw.

Well, the last, fifth proof of the existence of God in the scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas is the goal. Both rational and irrational creatures live in the world, however, regardless of this, the activities of both the first and the second are purposeful, which means that everything is controlled by a rational being.

Scholasticism - the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas

The Italian scientist and monk at the very beginning of his scientific work “Summa Theologica” writes that his teaching has three main directions.

- The first is God - the subject of philosophy, constituting general metaphysics.

- The second is the movement of all rational consciousnesses towards God. He calls this direction ethical philosophy.

- And the third is Jesus Christ, who appears as the path leading to God. According to Thomas Aquinas, this direction can be called the doctrine of salvation.

The meaning of philosophy

According to the scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas, philosophy is the handmaiden of theology. He attributes the same role to science in general. They (philosophy and science) exist in order to help people comprehend the truths of the Christian religion, because although theology is a self-sufficient science, in order to assimilate some of its truths there is a need to use natural science and philosophical knowledge. That is why it must use philosophy and science to explain Christian doctrines clearly, clearly, and more convincingly to the people.

The problem of universals

The scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas also includes the problem of universals. Here his views coincided with those of Ibn Sina. There are three types of universals in nature - in the things themselves (in rebus), in the human mind and after things (post res). The first constitute the essence of a thing.

In the case of the latter, the mind, through abstraction and through the active mind, extracts universals from certain things. Still others indicate that universals exist after things. According to Thomas' formulation, they are "mental universals."

However, there is a fourth type - universals, which are in the divine mind and they exist before things (ante res). They are ideas. From here Thomas concludes that only God can be the primary cause of everything that exists.

Works

Thomas Aquinas's main scientific works are the Summa Theologica and the Summa Contra Pagans, which is also called the Summa Philosophia. He also penned such scientific and philosophical work as “On the Rule of Sovereigns.” The main feature of the philosophy of St. Thomas is Aristotelianism, since it carries such features as life-affirming optimism in connection with the possibilities and significance of theoretical knowledge of the world.

Everything that exists in the world is presented as unity in diversity, and the singular and individual as the main values. Thomas did not consider his philosophical ideas original and argued that his main goal was to accurately reproduce the main ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher - his teacher. Nevertheless, he put Aristotle's thoughts into a modern medieval form, and so skillfully that he was able to raise his philosophy to the rank of an independent doctrine.

The importance of a person

According to Saint Thomas, the world was created precisely for the sake of man. In his teachings he exalts it. In his philosophy, such harmonious chains of relationships as “God - man - nature”, “mind - will”, “essence - existence”, “faith - knowledge”, “individual - society”, “soul - body”, “ morality - law", "state - church".

Unlike Aristotle, Thomas recognizes monarchy, not polity, as the best form of government.

He believed that according to the nature of things one must rule, because:

there is one God in the universe;

Among the many parts of the body, there is one that moves everything - the heart;

Among the parts of the soul, one dominates - the mind;

Bees have one king.

According to life experience provinces and city-states that are governed by more than one, overcome by discord, “and, on the contrary, provinces and city-states that are governed by one sovereign enjoy peace, are famous for justice and rejoice in prosperity.” The Lord speaks through the mouth of the Prophet (Jeremiah, XII, 10): “Many shepherds have spoiled my vineyard.”

According to R. Tarnas, Thomas Aquinas “turned medieval Christianity to Aristotle and the values that Aristotle proclaimed,” combining into a single whole “the Greek worldview in its entirety with Christian doctrine into a single great “sum”, where the scientific and philosophical achievements of the ancients found themselves included in the general body of Christian theology.”

The teaching of Thomas Aquinas has its followers. In particular, the modern Catholic theory of law (the neo-Thomist theory of law of J. Maritain (see 25.5) adopted Thomas’s idea of natural law and natural human rights (the right to life And continuation of the human race), which flow from the lex aeterna itself, which the state cannot encroach on by adopting the lex humana).

Dictionary

lexaeterna – eternal law

lexnaturalis – natural law

lexhumana – human law

lexdivina – divine law

2. Political and legal doctrine of Marsilius of Padua

Marsilius of Padua(1280-1343) - Italian political and legal thinker.

The logical basis of political and legal doctrine.

Marsilius of Padua was greatly influenced by Aristotle; being a Catholic, he referred to the Christian holy books: “Only the teaching of Moses and the Gospel, i.e. Christian, contains the truth.”

Unlike Thomas Aquinas, Marsilius was a supporter of the doctrine of double truth: there is “earthly truth,” which is comprehended by reason, and there is “heavenly truth,” which is comprehended by revelation and faith. These truths are independent and can contradict each other; “earthly truth” is inferior to “heavenly truth.”

Main job: “Defender of Peace” (“Defensor pacis”) (1324). In Defender of the Peace, Marsilius opposed the Catholic Church's claims to secular power. He believed that the attempts of the Catholic Church to interfere in the affairs of secular power sow discord in European states, therefore the clergy are the main enemies of the world. The book was condemned by the Catholic Church.

1.State and church.

Following Aristotle, Marsilius understands state as a perfect community (communitatis perfecta) of people, which is self-sufficient; based on the mind and experience of people; exists in order to “live and live well.” Marsilius rejects the doctrine of the divine origin of the state, and considers the biblical narrative about the establishment of social order among the Jews through Moses by God himself, only an unprovable object of faith.

Marsilius advocates the subordination of the church to the state. He is opposed to the papacy's claims to jurisdiction in the secular sphere and believes that the church should be under the control of the believers themselves, and not just under the control of the clergy and the pope. This should be expressed in the right of believers:

choose church officials, including the pope;

determine cases of excommunication of clergy;

approve the relevant articles of the church charter at a church council.

Marsilius deprives the clergy of the religious prerogative of being a mediator between God and people. The clergy should only be a mentor to the believers and perform church sacraments.

As the English historian of philosophy F.C. notes. Copleston, "Marsilius was a Protestant before Protestantism arose."

2. Legislative and executive powers of the state.

Legislative power must always belong to the people: “The legislator is the first efficient cause inherent in the law - the people themselves, the collective of citizens (universitas), or the most important part of it (valentior pars), expressing their choice and their will regarding everything relating to civil acts, non-execution who are threatened with completely earthly punishment.”

Why should the people or their representatives make laws? Marsilius puts forward the following arguments:

the people better obey the laws that they themselves have established;

these laws are known to everyone;

everyone can notice the omission in the creation of these laws.

Marsilius was a supporter of the election of the highest executive power by the people. The election of the head of this power is preferable to the transfer of power by inheritance: “...We called election the most perfect and excellent of the ways of establishing dominance.”

The idea of the people electing the head of the executive branch came from the practice of governing the Italian city republics and the procedure for electing the Holy Roman Emperor.

Legal theory. Marsilius recognizes the polysemy of the term “law” (Table 7). He is a proponent of understanding the law “in the strict sense of the word.”

Marsilius understands law as the law of the state. Law is an instructive and coercive “rule” that:

“exists in all communitatis perfecta”;

reinforced by a sanction that has “enforceable force through punishment or reward”;

has the “ultimate goal” of ensuring “civil justice”, i.e. earthly justice, identifying what is “fair or unfair, useful or harmful”;

established by the secular legislator.

This understanding of the law allows Marsilius to draw the following conclusions.

1. Divine law is not law in the proper sense. It is comparable to the doctor’s prescriptions (remember that Marsilius is a doctor). The purpose of divine law is to achieve eternal bliss. This law determines the differences between sins and merits before God, punishments and rewards in the other world, where Christ is the judge. Therefore, according to Marsilius, the clergy can only preach Christian teaching, but not force it in any way; a heretic can be punished only by God and only in the next world.

Marsilius opposed the church court and inquisitorial tribunals. In earthly life, a heretic can be expelled from the state if his teaching is harmful to society, but only secular power can do this. The priest, as a “physician of souls,” has the only right to teach and exhort.

The law of the church is not law in the proper sense, since it is provided only with spiritual sanctions. It can be enforced by temporal sanctions according to the will of the state, but then it becomes the law of the state.

Natural law is not law in the proper sense, it is only a moral law: “...There are people who call “natural law” the dictates of just reason regarding human actions, and natural law in this sense of the word includes the divine law.”

There must be a rule of law in a state, because “where there is no rule of law, there is no real state.”

The monarch, the government, the judges must rule on the basis of laws that must be promulgated: “... all sovereigns, and among them especially monarchs, who with all their descendants rule by succession, must, in order that their power be safer and more durable , to rule in accordance with the law, and not in defiance of it...”

The law allows:

to realize “civil justice and the common good”;

to avoid bias in the judicial decision, which can be influenced by the hatred, greed, love of the judge: “So, laws are necessary in order to exclude from civil judicial decisions or regulations the malice and errors of judges.”

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

on the topic “Thomas Aquinas as a systematizer of Aristotle’s teachings”

Thomas Aquinas is known to us not only as an independent thinker, but also as a systematizer of the teachings of Aristotle.

Since the 12th century. Europe, mainly through Arab and Jewish mediation, became acquainted with the legacy of Aristotle, in particular with his metaphysical and physical treatises, unknown until that time. Arabic versions were translated into Latin from the early 13th century. Aristotle was translated directly from Greek.

The activity of translating Aristotle led to a serious confrontation between Greek rationalism, represented by Aristotle, and the Christian, subrational understanding of the world. The gradual acceptance of Aristotle and his adaptation to the needs of the Christian understanding of the world had several stages, and although this process was controlled by the church, it did not happen without crises and upheavals.

The church initially responded to the interpretation of Aristotelianism in a pantheistic spirit (David of Dinant) by banning the study of Aristotle's works of natural science and even Metaphysics at the University of Paris (papal decrees of 1210 and 1215). Pope Gregory IX in 1231 confirmed these prohibitions, but at the same time instructed a specially created commission to examine the works of Aristotle regarding their possible adaptation to Catholic doctrine, which reflected the fact that the study of Aristotle had become at that time a vital necessity for university education and development of scientific and philosophical knowledge in Western Europe. In 1245 the study of Aristotle's philosophy was allowed without restrictions, and in 1255 no one could obtain a master's degree without studying the works of Aristotle.

The expansion of social, geographical and spiritual horizons associated with the Crusades, familiarity with the treatises of Aristotle and Arab natural science required the synthesis of all known knowledge about the world into a strict system in which theology would reign. This need was realized in large sums - works where the source material was the Christian image of the world, covering nature, humanity, the spiritual and visible world. Theology was thus presented as a scientific system grounded in philosophy and metaphysics.

In the middle of the 13th century. The opinion that theology needs to be revitalized by the philosophy of Aristotle has prevailed. However, there was a debate about how to apply it so as not to damage Christian theology. The scholastics were divided into two main camps. Conservative teaching insisted on preserving the main provisions of Augustine in theological matters, but at the same time using the philosophical elements of Aristotelianism. The progressive movement placed great emphasis on Aristotle, although here there was no complete dissociation from the traditions of Augustinian thinking. The growing influence of Aristotle finally resulted in a new theological and philosophical system, which was created by Thomas Aquinas.

In the Middle Ages it became clear that Augustinianism was not able to withstand the powerful influence of Aristotelianism. It was necessary to "mount" Aristotelian philosophy in order to eliminate the constant danger of deviation from Catholic orthodoxy. The adaptation of Aristotle to Catholic teaching became a vital necessity for the church. This task was carried out by the scholastics of the Dominican order, the most prominent of them being Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. Albert himself did not create a logically coherent, unified philosophical system. Only his student Thomas completed this task.

Thomas Aquinas was born around 1225. He was the son of Count Landolf Aquinas, and was raised by the Benedictines in Montecassino. He studied liberal arts at the University of Naples. At the age of seventeen he entered the Dominican order, which sent him to study in Paris. Albert the Great became his teacher, whom he followed in Cologne am Rhein. In 1252 he returned to Paris again to begin his academic activities there. While in Italy, he became acquainted with the works of Aristotle. His further stay in Paris (1268-1272) was very important; here he became a famous teacher of theology and became involved in polemical struggles and in resolving controversial issues. He died in 1274 on the way to the Leon Cathedral in the monastery of Fossanuova, near Terracino. For the gentleness and lightness of his character, he received the nickname “angelic doctor” (doctor angelicus). In 1368 his remains were transferred to Toulouse.

Thomas Aquinas is the author of many works devoted to issues of theology and philosophy. His main works are considered to be the Summa Theologica (1266-1274) and the Summa against the Pagans (1259-1264). The Summa Theologica (i.e., the totality of theological teachings) develops Catholic dogmatics. It becomes the main work of all scholastic theology.

Science and Faith

The areas of science and faith are quite clearly defined in Aquinas. The tasks of science come down to explaining the laws of the world. Aquinas also recognizes the possibility of achieving objective, true knowledge and rejects ideas according to which only the activity of the human mind is considered valid. Cognition should be directed primarily at the object, but in no case inward, at the subjective aspects of thinking.

And although knowledge is objective and true, it cannot cover everything. Above the kingdom of philosophical, metaphysical knowledge there is another kingdom, which is the concern of theology. You cannot penetrate here with the natural power of thinking. Here Aquinas differs from some of the authors of early scholasticism, for example Abelard and Anselm, who sought to make the entire area of Christian dogmatics comprehensible by reason. The area of the most essential sacraments of the Christian faith remains for Aquinas outside of philosophical reason and knowledge (for example: the trinity, resurrection, etc.). We are talking about supernatural truths such as divine revelation, good news, which are contained only in faith.

However, there is no contradiction between science and faith. Christian truth stands above reason, but it does not contradict reason. There can only be one truth, for it comes from God. The arguments that are put forward against the Christian faith from the standpoint of human reason contradict the higher, divine reason, and the means that the human reason has for such opposition are clearly insufficient. Aquinas constantly substantiated and proved this thesis in polemical treatises directed both against pagans and against Christian heretics.

Philosophy and theology

Philosophy must serve faith and theology by presenting and interpreting religious truths in the categories of reason, and by refuting as false arguments against faith. She is limited to this role. Philosophy itself cannot prove supernatural truth, but it can weaken the arguments raised against it. The understanding of the role of philosophy as a tool of theology finds its most perfect expression in Aquinas.

Thomist doctrine of being

The largest number of elements of Aristotle's teaching contains the Thomist doctrine of being. However, Aquinas abstracted from the natural scientific views of Aristotle and implemented primarily what served the requirements of Christian theology.

Like Augustine and Boethius, the highest principle in Thomas is being. By being, Thomas understands the Christian God who created the world, as described in the Old Testament. Distinguishing being and essence, Thomas nevertheless does not oppose them, but, following Aristotle, emphasizes their common root. Entities or substances have, according to Thomas, independent existence, in contrast to accidents (properties, qualities), which exist only thanks to substances. From here comes the distinction between the so-called substantial and accidental forms. The substantial form imparts simple existence to every thing, and therefore, when it appears, we say that something has arisen, and when it disappears, we say that something has collapsed. The accidental form is the source of certain qualities, and not the existence of things. Distinguishing, following Aristotle, actual and potential states, Thomas considers being as the first of the actual states.

Things become real, reality (existence) because forms that are separable from matter (either appear in a purely subsistent, ideal form, like angels and souls, or are the entelechy of the body) enter into passive matter. This is a significant difference between Aquinas’s ideas and Aristotle’s, in whom form always appears in unity with matter with one exception: the form of all forms - God - is incorporeal. The difference between the material and spiritual world is that the material, corporeal consists of form and matter, while the spiritual has only form.

In every thing, Thomas believes, there is as much being as there is actuality in it. Accordingly, he distinguishes four levels of the existence of things depending on the degree of their actuality, expressed in the way the form, that is, the actual principle, is realized in things.

At the lowest level of being, form, according to Thomas, constitutes only the external determination of a thing (causa formalis); this includes inorganic elements and minerals. At the next stage, the form appears as the final cause (causa finalis) of a thing, which is internally characterized by purposiveness, called by Aristotle the “vegetative soul,” as if forming the body from the inside - such are plants. The third level is animals, here the form is the efficient cause (causa efficiens), therefore the existing has within itself not only a goal, but also the beginning of activity, movement. At all three stages, form enters matter in different ways, organizing and animating it. Finally, at the fourth stage, form no longer appears as the organizing principle of matter, but in itself, independently of matter (forma per se, forma separata). It is spirit, or mind, the rational soul, the highest of created beings. Not being connected with matter, the human rational soul does not die with the death of the body. Therefore, the rational soul is called “self-existent” by Thomas. In contrast, the sensory souls of animals are not self-existent, and therefore they do not have actions specific to the rational soul, carried out only by the soul itself, separately from the body - thinking and volition; all animal actions, like many human actions (except for thinking and acts of will), are carried out with the help of the body. Therefore, the souls of animals perish along with the body, while the human soul is immortal, it is the most noble thing in created nature. Following Aristotle, Thomas considers reason as the highest among human abilities, seeing in nature itself, first of all, its rational determination, which he considers the ability to distinguish between good and evil. Like Aristotle, Thomas sees in the will practical reason, that is, reason aimed at action, and not at knowledge, guiding our actions, our life behavior, and not a theoretical attitude, not contemplation.

In Thomas's world, it is ultimately the individuals who truly exist. This peculiar personalism constitutes the specificity of both Thomistic ontology and medieval natural science, the subject of which is the action of individual “hidden essences” - “actors”, souls, spirits, forces. Beginning with God, who is a pure act of being, and ending with the smallest of created entities, each being has a relative independence, which decreases as it moves down, that is, as the relevance of the existence of beings located on the hierarchical ladder decreases.

For God, essence is identical with existence. On the contrary, the essence of all created things is not consistent with existence, for it does not follow from their individual essence. Everything individual is created, exists thanks to other factors, and thus has a conditioned and random character. Only God is absolute, not conditioned, therefore he exists with necessity, for necessity is contained in his essence. God is a simple being, an existent; a created thing, a being, is a complex being. The Thomistic solution to the problem of the relationship between essence and existence strengthens the dualism of God and the world, which corresponds to the main principles of Christian monotheism.

Universe conceptAliyah

In connection with the doctrine of form, let us take a closer look at Aquinas’s concept of universals, which expresses the position of moderate realism. First, the general concept (universals) exists in individual things (in rebus) as their essential form (forma substantiales); secondly, they are formed in the human mind by abstraction from the individual (postres); thirdly, they exist before things (anteres) as an ideal prefiguration of individual objects and phenomena in the divine mind. In this third aspect, in which Aquinas ontologizes the future in the sense of objective idealism, he differs from Aristotle.

Evidence for the existence of God

The existence of God can be proven, according to Aquinas, by reason. He rejects Anselm's ontological proof of God. The expression “God exists” is not obvious and innate to the mind. It must be proven. The Summa Theologica contains five proofs that are interrelated with each other.

Prime mover

The first is based on the fact that everything that moves is moved by something else. However, this series cannot be continued indefinitely, because in this case there would be no primary “mover”, and, consequently, that which is moved by it, since the next moves only because it is moved by the first. This determines the necessity of the existence of the first engine, which is God.

Root cause

Another proof comes from the essence of the efficient cause. There are a number of efficient causes in the world, but it is impossible for something to be an efficient cause of itself, and that is absurd. In this case, it is necessary to recognize the first efficient cause, which is God.

First need

The third proof follows from the relationship between the accidental and the necessary. When studying the chain of this relationship, you also cannot go to infinity. The contingent depends on the necessary, which has its necessity either from another necessary thing or in itself. In the end it turns out that there is a first necessity - God.

The highest degree of perfection

The fourth proof is the degrees of qualities, following each other, which are everywhere, in everything that exists, therefore there must be the highest degree of perfection, and again it is God.

Teleological

The fifth proof is teleological. It is based on utility, which manifests itself in all nature. Everything, even what seems random and useless, is directed towards a certain goal, has meaning, usefulness. Therefore, there is a rational being who directs all natural things towards a goal, and this is God.

Obviously, no special research should be undertaken to find out that these proofs are close to the reasoning of Aristotle (and Augustine). Arguing about the essence of God, Aquinas chooses a middle path between the idea of a personal God and the Neoplatonic understanding of God, where God is completely transcendental and unknowable. To know God, according to Aquinas, is possible in a threefold sense: knowledge is mediated by divine influence in nature, on the basis of the similarity of the creator and the created, for concepts resemble divine creations. Everything can be understood only as a particle of the infinite perfect being of God. Human knowledge is imperfect in everything, but still it teaches us to see as an absolute existence in itself and for itself.

Revelation also teaches us to see God as the creator of the universe (according to Aquinas, creation refers to realities that can only be known through revelation). In creation, God realizes his divine ideas. In this interpretation, Aquinas again reproduces Platonic ideas, but in a different form.

Problem hhuman soul

The most studied issues in the work of Thomas Aquinas include the problems of the human soul. In many of his treatises, he discusses feelings, memory, individual mental abilities, their mutual connections, and cognition. In doing so, he proceeds from the Aristotelian understanding of passive matter and active form. The soul is the formative principle operating in all life manifestations. The human soul is incorporeal, it is a pure form without matter, a spiritual substance independent of matter. This determines its indestructibility and immortality. Since the soul is a substance independent of the body, it cannot be destroyed by it and, like a pure form, cannot be destroyed by itself. Thus, Aquinas considers the human thirst for immortality to be proof of the immortality of the soul's substance, which contradicts Averroism, which recognizes immortality as an attribute only of the supra-individual spirit.

Aquinas comes from Aristotle, developing the theory of individual mental forces or properties. He distinguishes the vegetative soul inherent in plants (metabolism and reproduction), he distinguishes it from the sensitive soul that animals have (sensory perceptions, aspirations and free, voluntary movement). In addition to all this, a person has an intellectual ability - reason. Man has a rational soul, which also performs the functions of two lower souls (in this, Aquinas differs from the Franciscans, for example, from Bonaventure). Aquinas gives preference to reason over will. The intellect rises above the will. If we know things on the basis of their external reality, and not their internal essence, then this leads, among other things, to the conclusion that we know our own soul indirectly, and not directly, through intuition. The Thomist doctrine of the soul and knowledge is rationalistic. The ideas of the Dominican Thomas Aquinas strongly oppose the views of the Franciscans not only in the field of psychology but also in other areas. Franciscan theory emphasizes primarily the activity of human knowledge. Aquinas, referring to Aristotle, recreates the passive, receptive nature of knowledge. In cognition he sees a figurative perception of reality. If the image coincides with reality, then the knowledge is correct.

To the question about the sources of human knowledge, Aquinas answers, like Aristotle: the source is not involvement in divine ideas (or memories of them), but experience, sensory perception. All material of knowledge comes from the senses. The active intellect processes this material further. Sensory experience represents only an individual, singular thing. Actually, the object of the mind is the essence that is contained in individual things. Cognition of the essence is possible through abstraction.

Thomist ethics

Thomist ethics is also built on the doctrine of the soul. Aquinas considers free will to be a prerequisite for moral behavior. Here he also opposes Augustine and the Franciscan theory. As for the virtues, Aquinas, reproducing the four traditional Greek virtues: wisdom, courage, moderation and justice, adds three more Christian ones: faith, hope and love. The construction of the Thomist doctrine of virtues is very complex, but its central idea is simple. It is based on the premise that human nature is reason: whoever is against reason is also against man. The mind rises above the will and can control it. Aquinas sees the meaning of life in happiness, which, in the spirit of his theocentric worldview, he understood as knowledge and contemplation of God. Cognition is the highest function of man, while God is an inexhaustible subject of knowledge. The ultimate goal of man lies in knowledge, contemplation and love of God. The path to this goal is full of trials; reason leads a person to a moral order that expresses the divine law; the mind shows how one should behave in order to achieve eternal bliss and happiness.

Doctrine of the State

Aquinas, being an Aristotelian, like Albertus Magnus, was interested in the world. Albert's interest tended primarily to the natural world, to natural scientific issues. Aquinas was interested in the moral world and, thus, society. The center of his interests were spiritual and social problems. Like the Greeks, he places man primarily in society and the state. The state exists to take care of the common good. Aquinas, however, resolutely opposes social equality; he considers class differences to be eternal. Subjects must submit to their masters; obedience is their cardinal virtue, as is that of all Christians in general. The best form of state is a monarchy. The monarch must be in his kingdom what the soul is in the body, and what God is in the world. The power of a good and just king should be a reflection of God's power in the world.

The task of the monarch is to lead citizens to a virtuous life. The most important prerequisites for this are maintaining peace and ensuring the well-being of citizens. The external goal and meaning is the achievement of heavenly bliss. It is no longer the state that leads a person to it, but the church, represented by priests and the viceroys of God on earth - the Pope. The role of the church is higher than the state and therefore the rulers of this world must be subordinate to the church hierarchy. Aquinas proclaims the need for unconditional subordination of secular power to spiritual power; comprehensive power must belong to the church.

The main thing in the work of Thomas Aquinas is the classification-ordered method he developed for arranging, distinguishing and placing individual knowledge and information. Immediately after the death of Aquinas, a fierce struggle broke out for the leading role of Thomism in the order and throughout the Catholic Church. Resistance came primarily from Franciscan theology, oriented toward Augustine. For her, some features of Aquinas’s ontology and epistemology were unacceptable, for example, the fact that man has only one form (i.e., the activity of the soul), to which everything is subordinated; She also did not accept the denial of spiritual matter, the recognition of indirect knowledge of the soul.

At the end of the 13th beginning of the 14th century. Thomism prevailed in the Dominican Order. Aquinas was recognized as his "first doctor" in 1323. proclaimed a saint, in 1567 recognized as the fifth teacher of the church. The university in Paris (later Cologne am Rhein) became the stronghold of Thomism. Gradually Thomism became the official doctrine of the church.

Pope Leo XIII proclaimed on August 4, 1879 in the encyclical "Aeterni Paris" the teachings of Thomas Aquinas binding on the entire Catholic Church. In the 19th and 20th centuries. On its basis, neo-Thomism develops, divided into various directions.

Similar documents

Basic provisions of medieval philosophy. The emergence of scholastic philosophy in Western Europe. The heyday of scholasticism. Spiritual culture. Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. Questions of science and faith. The concept of universals. Problems of the human soul.

abstract, added 03/09/2012

The main sections of medieval philosophy are patristics and scholastics. The theories of Augustine - the founder of the theologically meaningful dialectics of history, about God, man and time. Thomas Aquinas on man and freedom, his proof of the existence of God.

presentation, added 07/17/2012