The plot of the bas-relief, where the tsar-guslar is surrounded by wild animals, has an analogue not only in the visual folk tradition, but also in Russian oral folklore. This is an apocryphal spiritual verse about Yegor the Brave, the ruler of all animals and the organizer of the Earth. Many have noticed that the image of Yegor the Brave has the features of an ancient demiurge and differs from the image of St. George the Victorious. Outstanding researcher of Russian folklore F.I. Buslaev compared him with the image of Väinämöinen.

The Holy Great Martyr George the Victorious (Cappodocia) lived in the 3rd century and was distinguished by courage, strength and honesty. He served as chief of the bodyguards of Emperor Diocletian.

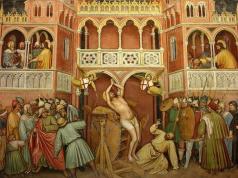

During the persecution of Christians, he distributed his property to the poor and voluntarily declared his religion before the emperor. Saint George was subjected to severe torture, inducing him to worship idols, but he was able to endure everything with amazing fortitude. At the same time, many miracles happened; after each torture, George was healed again. After Diocletian was convinced that he was unable to kill the saint or persuade the martyr to apostasy, George prayed and gave his soul to the Lord. According to another version, after eight days of severe torment in 303 (304), George was beheaded.

One of the most famous posthumous miracles of St. George is the killing of a serpent (dragon) that devastated a certain kingdom. When the lot fell to sacrifice the king’s daughter to the monster, Saint George appeared on horseback and pierced the snake with a spear. This appearance of the saint contributed to the conversion of local residents to Christianity.

Miracle of George about the serpent. Russian icon

In the Russian apocryphal tradition, this event is associated with Moscow. In the village of Kolomenskoye they still show Golosovoy Ravine, in which St. George the Victorious killed the snake. When the serpent was already struck by the saint’s spear, with his last strength he lashed out with his tail and hit the horse’s belly. From this blow, the horse’s stomach was cut as if by a sword, and its entrails fell to the ground. The horse rode a little away from the dead snake and fell. So George was left without a horse. And the insides were petrified, and the horse’s head was petrified. Below the stream there are four more small boulders - these are petrified horse hooves. Even in the early 90s, both Orthodox priests and Old Believers served prayers to St. George the Victorious near these stones.

“Horse Offal” – “Maiden Stone”

“Horsehead” – “Goose-Stone”

The stones lying there today are revered as the petrified entrails of George’s horse, who died in battle; the horse’s head is a “goose stone,” and the horse’s hooves. It was in connection with this legend that St. George the Victorious appeared on the coat of arms of Moscow, according to the old men who lived in neighboring villages.

The verse about Yegor the Brave is noticeably different from the life of St. George the Victorious. It seems that the verse consists of at least two parts: the first is a brief retelling of the life of the holy great martyr, and the second is some kind of Slavic legend, going back to the ancient image of a warrior-singer, preacher and organizer of the Russian Land. In the verse about Yegori the Brave we do not find any mention of the harp, just as there are none in the verse about the Dove Book. However, “the light Yegoriy” sings and with his songs does the same thing as Väinämöinen - he arranges the world: he distributes mountains to “their places”, spreads forests throughout Holy Rus', tames animals and birds with song, forcing them to serve God with prophetic words. It is significant that Russian folklore tradition considers Yegor the Brave the patron saint of all animals, and wolves do not eat anything without his permission and even serve him instead of dogs.

Illustration for the cartoon “Yegory the Brave”

Is it not from this, not from the once existing identity of the images of Yegor the Brave and the prince - the alleged ancestor of the Wends, named in the verse about the Book of the Dove by King David - that wolves appeared among the white stone bas-reliefs of the Vladimir-Suzdal churches?

Some researchers saw in the image of Saint Yegori the Brave the pagan god Yarila transformed in Christianity. There were several reasons for this: the consonance of the names Egor, Yuri, Yarila; the celebration of Yegor's Day in the spring, when, according to Slavic ideas, the god of fertility Yarila came to earth on a white horse, as well as the fact that in folk tradition the functions of the patron saint of animals and harvests, similar to the functions of Yarila, were assigned to the Holy Great Martyr George. We can only partially agree with this. Among the Slavs, as is known, many gods were deified ancestors, “princes and kings.” And the Slavic word “god” itself simply means “supreme”, “superior”. For example: “rich” - superior in property, “adore” - elevate, distinguish from others, “bozhatko” - uncle, godfather (Tver and Vologda), that is, eldest. There are many traces of this deification of real ancestors and historical characters in Slavic folklore. Such, for example, are the legends about Tsar Svarog, who established the laws, taught how to forge iron and plow the land; about Tsar Koshchei, the negative hero of many Russian fairy tales; about King Trojan, who melted away with the appearance of the sun. Thus, in the image of Yegor the Brave and in the plots of the poem about him, a dynastic myth about a certain Slavic king who miraculously escaped in childhood and then saved his mother can be traced.

There is also an interesting opinion of researcher Nikolai Savinov in his work “The Secret of Yegory the Brave.” Based on some similarities between the plot line of the spiritual verse and the biography of a real historical character, he concludes: “This is the Kiev prince Svyatoslav, nicknamed... Brave!”

There really are similarities, especially in the biography. However, it is not clear how the storytellers were able to change the name Svyatoslav into Yegory throughout the entire territory of the existence of the verse? There is no consonance, no similarity. Why is the verse about Yegor distributed mainly in the north of Russia and is practically absent in Ukraine? We know of no legends about Prince Svyatoslav Igorevich where he was a singer or guslar. And the myth of Yegoria itself, in a number of ways, seems much more ancient than the events during which Prince Svyatoslav lived. Prince Svyatoslav was, first of all, a commander and warrior, and Yegoriy was the organizer of the earth and the establisher of order, a demiurge in the first place. Attempts to directly identify epic characters with historical figures have not worked particularly well. The “historical school” has undoubtedly done a lot in the study of epics, but the approaches to working with myth have changed, and no one insists on the previous examples of a direct relationship between the epic Sadok and Sadko Sitnich, and Vladimir the Red Sun with Vladimir the Baptist. Science has moved away from this practice, finding a lot of shortcomings in this ratio. But Nikolai Savinov’s opinion is certainly interesting, it should be known and taken into account in the topic we are considering.

Many versions of the verse about Yegori the Brave have been written down. Three main regions where this verse was sung can be mentioned. Northern (with the most preserved and rich tradition) - on the Mezen, Pechora, on the shores of the White Sea. Central Russian - songs recorded in the Ryazan, Moscow, Voronezh regions of Russia. And Terek - among the Cossacks. In the records of only A.V. Markov, who recorded the “Verse about Yegor the Brave” in three subregions of the White Sea coast - the Zimny, Tersky and Pomeranian coasts, is found in twelve variants. In the folk song, in contrast to the life of the Holy Great Martyr George the Victorious, Yegoriy is not just the son of rich parents, but a princely or royal son, which distinguishes him from Saint George the Victorious and brings him closer to the image of the Tsar-Guslar from the “Pigeon Book”, as well as to the image Väinämöinen. A.V. Markov wrote that A.M. Kryukova, a famous performer of epics and spiritual poems, considered the verse about Yegoria to be antiquity (epics) and distinguished it from other spiritual poems. In other words, she recognized the verse as a historical memory, a legend about the prince-organizer of the Russian Land, who has special external signs:

Up to the elbows... hands in gold,

Knee-deep...legs in silver.

There are often little stars along the braids.

In the spiritual verse, Yegor the Brave saves his mother, and on the way to her he encounters “outposts,” obstacles that he removes by singing, simultaneously establishing order in the Universe:

Three outposts, three great ones:

Ishshe is the first outpost - dark forests,

There is no passage on horseback or on foot,

Yes, no clear falcon will fly,

Not for you, good fellow, there is no way.

Yes, my friend, that outpost - stone mountains,

They stand from the ground to the sky,

They stand from the east to the west,

There is no passage on horseback or on foot,

Yes, there is no flight for the clear falcon.

Ishshe the third outpost - fire river,

From the ground the flames are poached to the sky,

From the east it goes from the west.

He puts into place the crowded mountains that are preventing passage, pushes the “dark forests” apart, tames the fiery river with singing and overcomes it. No obstacles stop Yegory: “He stands firm and sings poetry.”

It is noteworthy that in “Kalevala” we encounter three deadly obstacles fencing the land of darkness Pohjola, in which “the sun does not shine and the moon does not shine.” These are wolves and bears, and a fiery eagle, and a fiery river.

We can conclude that the features of Yegor the Brave from the spiritual verse bring him closer to the images of Väinämöinen and the tsar-guslar David Evseich. Let's list the similarities:

1. They are all very wise.

2. All of them create order on Earth with song and word.

3. All of them are of the royal or princely family.

4. All of them, through music and poetry, have power over animals.

5. Verbal or pictorial iconography depicts them surrounded by animals.

6. All of them are capable of influencing inanimate nature with their singing.

7. The mythological events that occur with them are connected with Russia and already with the White Sea-Baltic region.

8. All these three legends are geographically (the place of their preservation and discovery) correlated primarily with the regions of the Russian north-west. The songs of the Kalevala were also collected by Elias Lönnrot in Russian Karelia, on the shores of the White Sea. Other Finnish peoples did not have such an epic.

Let us assume that all these three legends go back to a common root, the ancient legend about the progenitor of the princely (or royal) dynasty of the Slavic people of the Wends - Vened or Ven, remembered in the East Slavic fairy-tale epic as Ivan Tsarevich.

Vsevolod Merkulov, in his remarkable article “Ancient Russian legend, revived in Pushkin’s fairy tales,” drew attention to the fact that the fairy tale “About Tsar Saltan” by A.S. Pushkin goes back to the half-forgotten legends of the Baltic Slavs. These legends, which eventually became fairy tales, continued to live among the people and were passed on from mouth to mouth. “Even though Pushkin changed some details and added a share of poetic fiction, he kept the basis of the ancient Russian legend unchanged. Alas, these days it is hardly possible to hear and record something like this in endangered villages. The historical memory of our people fades away every year. And Pushkin’s fairy tales revive it, revive pride in its native past.” .

Great words! There is only one thing I cannot agree with the author I highly respect. At least as early as the second half of the 90s of the 20th century, ethnological expeditions of the St. Petersburg Rimsky-Korsakov Conservatory recorded these legends. Moreover, they were almost completely identical to those notes by Pushkin, in which he recorded in notes the fairy tales he heard. The amazing preservation of the texts in the memory of the storytellers! Although, of course, unfortunately, people's memory is fading.

In Russian fairy tales there is a plot that is repeated in a lot of variants, but is basically the same, and it was this that formed the basis of Pushkin’s “Tsar Saltan”. The plot and image of Yegor the Brave goes back to the corpus of these tales.

In all these legends, the main characters have distinctive external features that are recognized as hereditary. It is through them that the king recognizes his lost children. It is the bride’s ability to pass on to her children, to repeat these traits in her descendants, that is the reason for marriage: "At the King's Dodona there were three daughters. Ivan Tsarevich came to woo them: he had knee-deep legs in silver, elbow-deep arms in gold, a red sun on his forehead, and a shining moon on the back of his head. He began to woo King Dodon’s daughters: “I,” he says, “will take the one who in three bellies will give birth to seven young people - like myself, so that the legs are knee-deep in silver, the arms are in gold up to the elbow, the sun is red in the forehead, and the moon is shining at the back of the head.” The youngest daughter, Marya Dodonovna, jumped out and said: “I will give birth in three bellies to seven young men even better than you!” .

It is interesting that the plot of this tale begins to appear in German literature from the 17th century. Apparently, we are dealing with the German borrowing of this tale from the Baltic Slavs they conquered.

Let us recall that Yegor the Brave has the same hereditary distinctive features. He also has arms up to the elbows in gold, legs up to the knees in silver, a clear moon on the back of his head, and a red sun on his forehead. What are these special signs that appear at birth?

It is logical to assume that the listed features of the baby relate to widespread Slavic beliefs associated with the fact that a happy person will be born wearing a shirt. The Yaik Cossacks had a comic legend that “The ancient Cossacks were born immediately on horseback, with a pike and a saber. Then without a horse, but in uniform, and when the world completely deteriorated, then even this was gone, and if someone is now born in a shirt, then everyone says about him that he is happy.”

The helmet of the most famous representative of the Solar dynasty - King Rama with dynastic symbols of the sun on the forehead - “the sun is clear in the forehead”

This photograph shows a sculpture of the ancient Aryan moon god Soma, who, according to legend, became the founder of the Lunar Dynasty. Despite the poor quality of the photo, it is clear that he has “a bright moon on the back of his head”

The first princes and their descendants had to be born with signs of power and military service: in a helmet (the sun in the forehead, stars often on the braids), in armor: “silver” leggings and “golden” bracers.

The closest correspondence to the described design of the armor of Yegor the Brave we find, surprisingly, among the Aryan kings and heroes. The symbol of the moon and the sun, worn on helmets, denotes belonging to the two oldest Aryan royal dynasties: Lunar and Solar, called in the Mahabharata respectively: “Chandravamsha” or “Somavamsha” and “Suryavanshya”.

Our Yegory is brave and all the characters with the characteristic attributes mentioned in fairy tales must be descendants of the united “Solar-Lunar” dynasty. We probably have the opportunity to obtain at least some, albeit abstract, dating of the time referred to in fairy tales.

That is, following the storytellers who tell us that these signs are signs of the royal family, we can correlate Yegor the Brave with the fairy-tale character Ivan Tsarevich or with his descendant. Let us recall that through comparison with the myth of Väinämöinen, we raised the image of Yegor the Brave, more or less approximately, to a certain progenitor of the Wendish tribe, through kinship with the image of the tsar-guslar David Evseich with the royal-priestly family of the Slavs from the island of Ruyan. In this part of the study, in search of the prototype of Yegor the Brave, the comparison again leads us to the Baltic to the genealogical legends of the kings of Ruyan.

We dare to assume that all versions of these tales tell about one event - the resettlement of the Slavs to the Baltic - and especially clearly set out the legend about the beginning of the Russian-Ruyan royal dynasty on the island of Ruyan. The chronicler Helmold several times draws the attention of readers to the fact that “In the past, only the Slavs had a king.” “Svyatovit was revered throughout the Slavic Pomerania as the main deity, the Rana temple in Arkona was the first temple, and the Rana themselves were the elder tribe, and their king enjoyed special respect among the Baltic Slavs.”

In various versions of the tale, the king will have 7, then 9, or 33 sons. All children, except the last one, are hidden from the king in different ways by ill-wishers. Always one of them sails in a barrel with his mother to a deserted island. The description of the island is very consistent from fairy tale to fairy tale. On this island there is a high mountain, a bend in the seashore (Lukomorye), a huge oak tree, impenetrable forests and deep streams. It is on this mountain near the oak tree that the exiled prince builds his city. Then, having heard about the diva, the Tsar Father comes to visit this new city. The Blue Sea is the stable name for the Baltic Sea in the Novgorod land. The description of the fairy-tale island completely coincides with the real Ruyan (Rügen), and in fairy tales it is called almost the same - Buyan Island.

Ruyansk seaside. Famous white cliffs

Most likely, the tales are not even talking about Ruyan in general, but about the northern Cape Arkona on the Vitov Peninsula, where there was an ancient Slavic fortified settlement with a temple dedicated to Svyatovit in the center.

“The city of Arkona lies on the top of a high rock; from the north, east and south it is surrounded by natural protection... on the western side it is protected by a high embankment of 50 cubits...”

“In the middle of the city there was a square on which stood a temple made of wood, of the most elegant workmanship... The outer wall of the building stood out with neat carvings, rough and unfinished, which included the shapes of various things. It had a single entrance. The temple itself contained two fences, of which the outer one, connected to the walls, was covered with a red roof; the inner one, supported by four columns, had curtains instead of walls and was not connected with the outer in any way, except for a rare interlacing of beams.”

Many fairy tales mention how a prince and his mother climb a high mountain:

“The barrel was carried along the sea for a long time, and finally washed ashore; the barrel became aground. And the son of Princess Martha grew by leaps and bounds; He grew up big and said: “Mother! I'll reach out." - “Stretch, child!” As he reached out, the barrel instantly burst.

Mother and son went out to a high mountain. The son looked around in all directions and said: “If only there was a house and a green garden here, mother, we could live!” She says: “God willing!” At that time a great kingdom was established: glorious chambers appeared - white stone, green gardens - cool; a wide, smooth, well-trodden road stretches to those chambers.”

The tale probably refers to a rock called the “King’s Throne” (Konigstuhl), which rises 180 meters above the sea. A legend has been preserved on Rügen: in order to confirm their right to the throne, the Ruyan rulers had to independently climb the white rocks of the cliff from the sea to the very top.

Rock "Royal Throne" (Konigstuhl)

In the fairy tale we discover the legend that gave rise to this custom (incomprehensible without a fairy tale explanation). That is, the pretender to the throne who climbed onto the rock seemed to be making the island his own anew, like the legendary fairy-tale ancestor-first settler. By this he confirmed his right, showing that he was similar to the legendary ancestor.

The prince, like Yegor the Brave, is a demiurge, puts the world in order around himself, builds “white stone chambers,” creates green gardens, groves and fills the island with all sorts of miracles.

A special place in all versions of fairy tales is occupied by the image of a huge oak tree. According to fairy-tale legends, near this tree on the island, a witch hides the prince’s older brothers from the king, or, alternatively, there is a tethered cat near him who knows secret legends. In Pushkin's fairy tale, the main character makes his first weapon - a bow - from an oak branch. It is known that among the Slavs the oak was considered a sacred tree and was even revered as a symbol of the supreme god.

N.K. Roerich. Set design for the opera by N.A. Rimsky-Korsakov “The Tale of Tsar Saltan.” 1919

The German author Herbord mentions the veneration of oak forests and oaks in the land of the Pomeranians by the Baltic Slavs at the beginning of the 12th century: “There was also a huge leafy oak tree in Stetin, with a pleasant spring flowing under it; the common people considered the tree sacred and gave it great honor, believing that some kind of deity lived here. When the bishop wanted to cut down the oak tree, the people asked to leave it, promising in the future not to associate any religious worship with this place and tree, but to use them for simple pleasure.”

Despite some plot differences, the oak tree in mythological texts is always mentioned as some important feature of Buyan Island:

“Yaga Baba came and began to do her job: she took three sons from Martha the Beautiful, and left three filthy puppies in their place; Then she went into the forest and hid the children in a dungeon, near an old oak tree.”

And if we remember the symbolism of the stone carvings on the Dmitrovsky Cathedral in Vladimir, then there, among other images, a certain tree, similar to a stylized oak in the form of the letter “Zh” - “life”, occupies one of the most significant places.

In fairy tales we also find mention of animals that became family emblems among Russian princes. So, in one version of the fairy tale, the brothers are turned into wolf cubs by their villainous aunt: “And at that time the queen gave birth to a son. Legs up to the knees in gold, arms up to the elbows in silver, with a pearl on every hair. The prince's elder sister carried him to the bathhouse. In the dressing room she hit him on the back and said:

– You were a royal child, or you were a gray wolf cub. The prince turned into a gray wolf cub and ran into the forest.”

Only mother's milk can disenchant princes:

“Go straight into the untrodden forest, there live two gray wolves in a hut, these are the two prince brothers. Take two wheat breads with you and knead the dough with mother’s milk. The wolves will grab those loaves of bread and immediately become people.”

“The wolves grabbed a white loaf of bread, swallowed them, smelled their mother’s milk, hit the floor, became princes: their legs were in gold up to their knees, their arms were in silver up to their elbows, and there was a pearl on every hair.”

Isn’t this a family tradition of the Lutich-Vilians, preserved in a fairy tale; wasn’t it their legendary ancestors in the genealogical myth who ran as wolf princes through the forest? This tale, perhaps, explains the origin of the name of the tribal union, for the Lutichi and the Viltsy are wolves, literally “wolves,” descendants of wolves. Moreover, legend says that there were at least two wolf brothers. It can be assumed that, in connection with the widespread Slavic tradition of the emergence of tribal ethnonyms, one of the fairy-tale wolf princes was called Lyut, and the other was called Wilts, or Wilt. As you know, the Lutich-Viltsy were a large tribal union. If everything is so, then we were right in assuming the possible reasons for the appearance of wolves on the stone bas-relief of the Dmitrov Cathedral in Vladimir. The wolf is a symbol of the princely dynasty of the Lutich-Vilts. This is probably why, in connection with the genealogical tradition of the Baltic Slavs, Yegor the Brave, patronymic of the Vilts-Lutichs, becomes the patron of wolves in later folklore tradition.

We find a version of the same fairy tale in which lions appear:

“And you, my children, where were you born and raised?” “We ourselves don’t know where we were born; and grew up on this island, us lioness she gave me her milk to drink.”

Here the fellows took off their caps, Marya Dodonovna looked, and they all had a red sun on their foreheads, and a moon shining on the back of their heads. “Oh, my dear children! Apparently, you are my fools!”

In ancient times, milk kinship (kinship through a wet nurse) was revered on a par with blood kinship.

In the wonderful book “Where do the Varangian guests come from?”, dedicated to the genealogy of Rurik and the Varangian princes, V.I. Merkulov repeatedly draws readers' attention to the fact that “The northern peoples made it a rule to trace their ancestry to the gods. The Younger Edda, for example, traced the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian dynasties to Odin, and he, in turn, called him a descendant of the Trojan kings. The dynasty of Vandals and Russians went back to semi-legendary and divine characters, which is reflected in their names." .

The author also emphasizes: “The names of the “Russian” kings were a kind of continuation of the genealogy of the “Russian” gods. The ancestor of the dynasty, Radegast, bore the same name as the main deity in the temple of Retra. Adam of Bremen wrote about the Retra sanctuary as a center of pagan worship. The main place there was occupied by the golden idol of Radegast with a lion’s head, especially revered by the Obodrites.”

That is, the lion as a dynastic and genealogical symbol of the Vladimir-Suzdal princes could well go back to the genealogical myth preserved in the fairy tale cited above. And the princely dynasty itself could once trace its ancestry back to the mythical lion-like Radegast, the ancestor of the princely family. Perhaps this is why the lion became the family sign of the descendants of Radegast - the Vladimir-Suzdal princes.

The fairy-tale legend is reminiscent of the Etruscan legend about Romulus and Remus, the founders of the city of Rome, who were suckled by a she-wolf, only in our legend there is a lioness instead of a she-wolf.

Capitoline wolf, ca. 500–480 BC e. Lupa Capitolina

The mentioned versions of this tale reflect the genealogical traditions of the ancient Slavic princely families from the southern Baltic coast. They tell the story of the origin of noble families from Tsar Ivan, who used the symbol of a lion (the heirs of Radegast - the Vladimir-Suzdal dynasty) and a wolf (the Lyutici-Viltsy) as their family emblem. At the cathedral in Vladimir, in the list of these symbols we also find a griffin (Pomorians). The falcon emblem (Rurikovich) should also be included in this list, probably the heraldic symbol of the younger brother - the fairy-tale prince, who sailed with his mother to Ruyan in a barrel. It was his family that became the eldest in the princely dynasty.

Rurikovich, Vladimir-Suzdal princes, Lutich-Viltsy, Pomeranian princes

All the adventures of the princes end when Tsar Ivan, their father, comes to their island. He recognizes his sons by his special hereditary characteristics and remains to live with them on the island:

“Hello,” they say, “dear father! How happy the king was here! And he stayed on the island to live with his family. And the evil sisters were put in a barrel, tarred with hot resin, and lowered into the sea-ocean. Serves them right!”

Or this option:

“The prince went to the new kingdom; whether long or short, I saw a great city; stopped at the white stone chambers. Martha the Beautiful and nine sons came out to meet; They hugged and kissed, shed many sweet tears, went to the chambers and made a feast for the whole baptized world. I was there, I drank beer and wine, it flowed down my mustache, but it didn’t get into my mouth.”

With his move, described in the myth, Tsar Ivan moves the center of his kingdom to a new place. A new Slavic mystical and political center is emerging, a new “navel of the earth” - the fabulous island of Buyan - historical Ruyan.

The Holy Great Martyr George the Victorious, also known as Yegor (Yuri) the Brave, is one of the most revered saints in Christianity: temples and churches were erected in his honor, epics and legends were composed, and icons were painted. Muslims called him Jirjis al Khidr, the messenger of the prophet Isa, and farmers, cattle breeders and warriors considered him their patron. The name “George” was taken by Yaroslav the Wise at baptism and on the coat of arms of the capital of Russia it is Yegor the Victorious that is depicted and the most honorable award - the Cross of St. George - is also named in his honor.

Origin of the Saint

The son of Theodore and Sophia (according to the Greek version: Gerontius and Polychronia), Yegor the Brave was born in 278 (according to another version in 281) into a family of Christians living in Cappadocia, an area located in Asia Minor. According to ancient legends of Byzantium, Ancient Rus' and Germany, George's father is (Stratilon), while his life story is very similar to the life of his son.

When Theodore died, Yegor and his mother moved to Palestine Syria, to the city of Lydda: there they had rich possessions and estates. The guy entered the service of Diocletian, who then ruled. Thanks to his skills and abilities, remarkable strength and masculinity, Yegori quickly became one of the best military leaders and received the nickname Brave.

Death in the name of faith

The emperor was known as a hater of Christianity, cruelly punishing everyone who dared to go against paganism, and having learned that George was a devout follower of Christ, he tried various methods to force him to renounce his faith. Having suffered repeated defeats, Diocletian in the Senate announced a law giving all “soldiers for the true faith” complete freedom of action, even to the point of killing infidels (that is, Christians).

At the same time, Sophia died, and Yegori the Brave, having distributed all his rich inheritance and property to homeless people, came to the emperor's palace and openly admitted himself to be a Christian once again. He was captured and subjected to many days of torture, during which the Victorious One repeatedly demonstrated the power of the Lord, recovering from mortal wounds. At one of these moments, the emperor’s wife Alexandra also believed in Christ, which hardened Diocletian’s heart even more: he ordered George’s head to be cut off.

It was 303 AD. The brave young man, who exposed the darkness of paganism and fell for the glory of the Lord, was not yet 30 years old at that time.

St. George

Already from the fourth century, temples of St. George the Victorious began to be erected in different countries, offering prayers to him as a protector and glorifying him in legends, songs and epics. In Rus', Yaroslav the Wise designated November 26 as the feast of St. George: on this day they offered him thanks and praise, and cast amulets for good luck and invulnerability in battles. People turned to Yegor with requests for healing, good luck in the hunt and a good harvest; most warriors considered him their patron.

The head and sword of Yegori the Brave are kept in San Giorgia in Velur, under the main altar, and his right hand (part of the arm up to the elbow) in the monastery of Xenophon in Greece, on the sacred Mount Athos.

Day of Remembrance

April 23 (May 6, new style) - According to legend, it was on this day that he was beheaded. This day is also called “Yegory vershny” (spring): on this day, cattle breeders released livestock onto pastures for the first time, collected medicinal herbs and carried out the ritual of bathing in the “healing Yuriev dew”, which protected against seven diseases.

This day was considered symbolic and divided the year into two halves (together with Dmitriev's day). There were many signs and sayings about St. George's Day, or the day of the Unlocking of the Earth, as it was also called.

The second holiday of veneration of Yegor the Brave fell on November 26 (December 9, new style) and was called Yegor Autumn, or Cold. There was a belief that on this day St. George released wolves that could harm livestock, so they tried to place the animals in a winter stall. On this day they prayed to the saint for protection from wolves, calling him “the wolf shepherd.”

In Georgia, Giorgoba is celebrated annually on April 23 and November 10 - the days of St. George, the patron saint of Georgia (there is an opinion that the country received its name in honor of the great St. George: Georgia - Georgia).

Veneration in other countries

In many countries of the world, St. George the Victorious is one of the main saints and protectors:

George the Victorious is highly revered in many European countries, and in each his name is transformed in connection with the tradition of the language: Dozhrut, Jerzy, George, Georges, York, Egor, Yuri, Jiri.

Mention in folk epic

Legends about the exploits of the saint are widespread not only in the Christian world, but also among people of other beliefs. Each religion slightly changed minor facts, but the essence remained unchanged: Saint Yuri was a courageous, brave and fair defender and true believer, who died for his faith, but did not betray his spirit.

The tale of Yegor the Brave (another name is “The Miracle of the Serpent”) tells how a brave young man saved the young daughter of the ruler of the city, who was sent to be slaughtered by a monster from a lake with a terrible stench. The snake terrorized the inhabitants of a nearby settlement, demanding children to be eaten, and no one could defeat it until George appeared. He cried out to the Lord, and with the help of prayers immobilized the beast. Using the belt of the rescued girl as a leash, Yegory brought the serpent into the city and, in front of all the inhabitants, killed it and trampled it with a horse.

“The epic about the brave Yegor” was recorded by Peter Kireevsky in the mid-nineteenth century from the words of old-timers. It tells about the birth, growing up of Yuri and the campaign against the Busurman Demyanishch, who trampled on the glory of the Lord. The epic very accurately conveys the events of the last eight days of the great saint, telling in detail about the torment and torture that Yegor had to endure, and how each time the angels resurrected him.

"The Miracle of the Saracen"

A very popular legend among Muslims and Arabs: it tells about an Arab who wanted to express his disrespect for Christian shrines and shot an arrow at the icon of St. George. The Saracen's hands became swollen and lost sensitivity, he was overcome with fever, and he appealed to the priest from this temple asking for help and repentance. The minister advised him to hang the offended icon over his bed, go to bed, and in the morning anoint his hands with oil from the lamp, which was supposed to burn all night near this icon. The frightened Arab did just that. The healing amazed him so much that he converted to Christianity and began to praise the glory of the Lord in his country.

Temples to the glory of the saint

The first temple of St. George the Victorious in Rus' was built in Kyiv in the 11th century by Yaroslav the Wise; at the end of the 12th century, the Kurmukh Temple (Church of St. George) was founded in Georgia. In Ethiopia there is an unusual temple in honor of this saint: it was carved out of rock in the form of a Greek cross in the 12th century by a local ruler. The shrine goes 12 meters into the ground, spreading out in width to the same distance.

Five kilometers from Veliky Novgorod is the Holy Yuryevsky Monastery, which was also founded by Yaroslav the Wise.

The Russian Orthodox monastery in Moscow arose on the basis of the small church of St. George and became the ancestral spiritual place of the Romanov family. Balaklava in Crimea, Lozhevskaya in Bulgaria, the temple on Pskov Mountain and thousands of others - it was all built for the glory of the great martyr.

The symbolism of the most famous image

Among icon painters, Yegoriy and his exploits were of interest and popularity: he was often depicted as a fragile young man on a white horse with a long spear slaying a dragon (serpent). The meaning is very symbolic for Christianity: the serpent is a symbol of paganism, baseness and meanness, it is important not to confuse it with a dragon - this creature has four legs, and the serpent has only two - as a result, it always crawls with its belly on the ground (a creeper, a reptile - a symbol of meanness and lies in ancient beliefs). Yegory is depicted with a young clergyman (as a symbol of nascent Christianity), his horse is also light and airy, and Christ or his right hand was often depicted nearby. This also had its own meaning: George did not win on his own, but thanks to the power of the Lord.

The meaning of the icon of St. George the Victorious among Catholics is somewhat different: there the saint is often depicted as a well-built, strong man with a thick spear and a powerful horse - a more down-to-earth interpretation of the feat of a warrior who stood in defense of righteous people.

George the Victorious - in Russian. folklore Yegor the Brave, Muslim. Jirjis), in Christian and Muslim legends, a warrior-martyr, with whose name folklore tradition has associated the relict pagan ritual of spring cattle-breeding and partly agricultural cults and a rich mythological topic, in particular the motif of dragon fighting. Orthodox Christian hagiographic literature speaks of George as a contemporary of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305), a native of eastern Asia Minor (Cappadocia) or the adjacent Lebanese-Palestinian lands, who belonged to the local nobility and rose to a high military rank; During the persecution of Christians, they tried to force him through torture to renounce the faith and in the end they cut off his head. This puts George on a par with other Christians. martyrs from the military class (Dmitry Solunsky, Fyodor Stratilates, Fyodor Tiron, Mauritius, etc.), who, after the transformation of Christianity into the state religion, began to be considered as heavenly patrons of the “Christ-loving army” and perceived as ideal warriors (although their feat is not associated with courage battlefield, but in the face of the executioner). The features of a brilliant aristocrat (“komit”) made George a model of class honor: in Byzantium - for the military nobility, in the Slavic lands - for princes, in the West. Europe - for knights. Other motives are accentuated by the popular veneration of George, which went beyond the Christian circle (Byzantine legend tells of a formidable miracle that taught the Arab conquerors to respect George). George acts as the personification of the life-giving spring (“Zeleni Juraj” of Croatian ritual), and therefore Muslim legends especially emphasize his triple death and revival during torture. The motif of life in death, symbolizing the Christian mysticism of martyrdom, but also appealing to the mythological imagery of peasant beliefs, is not alien to Byzantine iconography, which depicted George standing in prayer with his own severed head in his hands (as on the icon kept in the Historical Museum in Moscow); the same motive became the reason for confusion among Muslims. countries of George (Jirjis) with Khadir (the meaning of this name is “green” - comparable to the folklore epithet George) and Ilyas. The spring holiday of St. George - April 23, was celebrated in the Eastern European and Middle Eastern areas as a seasonal milestone in the pastoral calendar: on this day, cattle were driven out to pasture for the first time, the first spring lamb was slaughtered, and special songs were sung (cf. Kostroma song: “We walked around the field, we called out to Yegor... You are our brave Yegor..., you save our cattle in the field and beyond the field, in the forest and beyond the forest, under the bright moon, under the red sun, from the predatory wolf, from the fierce bear, from the evil beast"); The ritual driving of the Sultan's horses to pasture was appointed for this day by the palace structure of Ottoman Turkey. Apparently, the Slavic peoples transferred to George some features of spring fertility deities like Yarila and Yarovit, which may be associated with folk versions of his name such as Yuri, Yury, Yur (Ukrainian), Ery (Belarusian). The Russian peasant called George a “cattle beater” and even a “cattle god”; however, as the patron saint of the cattle breeder, George already appears in Byzantium. the legend of the miraculous multiplication of Theopist's cattle. This line of veneration of George crossed with the military, princely-knightly line based on the special connection of George with horses (in the feat of dragon fighting, he is usually depicted as a horseman). Protecting livestock and people from wolves, George turns out to be the master of wolves in Slavic beliefs, which are sometimes called his “dogs.” He also turns away snakes from humans and domestic animals, which is associated with his role as a serpent slayer (dragon slayer): legend attributed to him the slaying of the chthonic monster, this most popular feat of the demiurge gods (for example, Marduk, Ra, Apollo, Indra, partly Yahweh) and heroes (for example, Gilgamesh, Bellerophon, Perseus, Jason, Sigurd, etc.). It is said that near a certain pagan city (localized sometimes in Lebanon, sometimes in Libya or in other places) there was a swamp in which a man-eating snake settled; as always in such cases, he was given boys and girls to eat, until the turn or lot came to the daughter of the city ruler (Andromeda motive). When she awaits death in tears, George, passing by and heading to the water to water his horse, finds out what is happening and waits for the snake. The duel itself is rethought: at the prayer of George, the exhausted and tamed serpent (dragon) himself falls at the feet of the saint, and the girl leads him into the city on a leash, “like the most obedient dog” (an expression from the “Golden Legend” of the Italian hagiographer Jacob of Voraginsky, 13th century. ). Seeing this spectacle, all the townspeople, led by the ruler, are ready to listen to George’s sermon and be baptized; George kills the snake with a sword and returns the daughter to her father. This story, in which George appears simultaneously as a hero, as a preacher of the true faith and as a chivalrous defender of doomed innocence, is already known in the grassroots, semi-official Byzantine hagiography. The episode of dragon fighting has been especially popular since the Crusades in the West. Europe, where it was perceived as a sacred crown and justification of the entire complex of courtly culture. The crusaders who visited the places of the legendary homeland of George spread his glory in the West, saying that during the storming of Jerusalem in 1099 he took part in the battle, appearing as a knight with a red cross on a white cloak (the so-called cross of St. George, in England since the 14th century; George is considered the patron saint of England). The “adventure” of the battle with the serpent, fearlessly undertaken to protect the lady, introduced the spirit of a chivalric romance into religious and edifying literature and painting; This specific coloring of the legend about George acquired special significance at the end of the Western Middle Ages, when the declining institution of chivalry became the subject of deliberate cultivation (created precisely for this purpose in about 1348, the English Order of the Garter was placed under the special patronage of George). The theme of dragon fighting supersedes all other motifs in George’s iconography and forms the basis of numerous works of art. An interesting exception is the Russian spiritual poems about “Yegory the Brave,” which ignore this topic. In them, George turns out to be the son of Queen Sophia the Wise, reigning “in the city of Jerusalem”, “in Holy Rus'”, his appearance is endowed with fabulous features (“Egor’s head is all pearl, there are stars all over Yegor”); from the “king of Demyanishch,” i.e. Diocletian, he suffers imprisonment for his faith in an underground dungeon for 30 years (both this imprisonment “in a deep cellar” and the 30-year imprisonment of a hero are constant motifs of epics), then miraculously emerges into the world and walks across Russian soil to establish Christianity on it. He sees his three sisters, ossified in paganism, as wild shepherds of a wolf pack overgrown with scabs and hair; from the water of baptism, the scabs fall off from them, and the wolves, like snakes, retreat under the ordering power of George. It all ends with the heroic duel of George with the “Tsar Demyanishch” and the eradication of “infidelism” in Rus' (acting as the equivalent of the ecumene). From the 14th century the image of a rider on a horse becomes the emblem of Moscow (then included in the coat of arms of Moscow, and later - in the state emblem of the Russian Empire). In 1769, the military order of St. was established in Russia. Great Martyr and Victorious George, in 1913 the military Cross of St. George.

Among the literary developments of the legend of George, we note three works by Russian. literature of the 20th century Behind the poem (“cantata”) by M. Kuzmin “St. George" stands for religious studies of the late 19th - early. 20th centuries, seeking in Christ. apocryphal topics of pagan myths (the princess herself identifies or compares herself with Kore-Persephone, Pasiphae, Andromeda and Semele; George has “Perseus’s horse” and “Hermes’s petas”), as well as psychoanalysis, which postulates an erotic meaning for the dragon-fighting motif; The background is the extreme oversaturation of each line with cultural and historical associations. On the contrary, B. Pasternak’s poem “The Tale” frees the motif of snake fighting from the entire burden of archaeological and mythological scholarship, from all random details (right down to the name of the hero himself), reducing it to the simplest and “eternal” components (pity for a woman, fullness of life and hope in the face of mortal danger). Finally, the prose “The Tale of Tsarevich Svetomir” by Vyach. Ivanova (unfinished) uses not the well-known theme of the battle with the serpent, but the motifs of Russian spiritual poems (George’s wild sisters, his mysterious power over wolves, etc.), trying to extract from them the archetypes of the Slavic tradition, with an eye to the Byzantine influence.

George the Victorious, or Yegor the Brave, as he was popularly called, was one of the most revered saints among the Russians. According to church tradition, St. George was born at the end of the 2nd century in Cappadocia, a region in Asia Minor. The life of the saint tells that he was a military leader under the emperor Diocletian, known for his merciless persecution of Christians. For professing the Christian faith, George was subjected to cruel torture, but endured the torture with patience and courage. In 303, at the age of about thirty, he was executed.

The lives and apocryphal literature describe the miracles performed by St. Georgiy. The most popular among the people was the “Miracle of the Serpent.” The story of the victory of St. George over the monster - the “fiery serpent”, which came to Rus' from Byzantium, was widespread in the monuments of ancient Russian writing. It told the story of the rescue of princess Elisava by a young warrior, who was doomed to be sacrificed to a dragon who settled in the land of Laodicea. In the name of God, George cursed the monster and ordered the princess to throw a girl’s belt around his neck, which is why the serpent obediently followed Elisava and George into the city. Here, in a large square, the saint pierced the monster with a spear in front of many townspeople who, having seen the miracle, believed in Christ.

Saint George.

According to the hagiographic description of the saint’s torment and the apocryphal legend about his fight against serpents, George was perceived by official Christianity as an ideal warrior. He was worshiped as a martyr and the heavenly patron of warriors. From about the 5th century, Byzantine emperors began to perceive St. George and as his patron. The Russian princes followed their example. The name George was one of the favorites of the Kyiv princes. To establish the cult of St. Yaroslav the Wise, who received the name George at baptism, did especially a lot for George in Rus'. In honor of his patron, in 1030 he founded the city of Yuryev, and in 1037 he began building the St. George Monastery in Kyiv. The day of the consecration of the first church of St. George in Rus' - November 26, 1051 - was marked by the establishment of an annual celebration. From the 10th to the 13th centuries, churches in honor of this saint were also built in Novgorod, Yuryev-Polsky, Staraya Ladoga and other cities. During services, excerpts from the life and miracles of the saint were read.

Traditional ideas about St. George is reflected in spiritual poems, where he is conceptualized as a defender of the Christian faith in Rus'. In the texts of this genre, along with the reproduction of descriptions of the martyrdom of Yegori, there were also motives for the creation of the Russian land by the saints and its liberation from “Ba-Surmanshchina” - paganism. At the same time, the image of St. George was influenced by the Russian epic tradition, including its mythological basis. The saint is endowed with an appearance that distinguishes fairy-tale and epic characters of a mythological nature: “His legs are in pure silver up to his knees, his arms are in red gold up to his elbows, Yegory’s head is all pearl, all over Yegory there are stars”; “The sun is red in the forehead, / The moon is bright in the back of the head.” In spiritual verses on the story of the liberation of Rus' by Yegor the Brave, the saint is called the son of the Jerusalem, and sometimes Russian, Queen Sophia the Wise, which explains his unusual nature, since “Sophia” is the “Wisdom of God.”

The spiritual verse tells of the seizure of power in Rus' by the “infidel king Demyanishch,” whose image is correlated with a historical figure - Emperor Diocletian. Demyani also attacks Jerusalem, destroys it and, under threat of death, invites Yegoriy to renounce the Christian faith. To force Yegoriy to convert to the “infidel” faith, he is sawed with saws, chopped with axes, boiled in resin, but, despite the torment, Yegoriy continues to pray - “sing cherubic verses, pronounce all the voices of angels.” Having achieved nothing, De-myanishche throws Yegor into a deep cellar for 30 years. After this time, the saint is miraculously liberated: the Mother of God appears to him in a dream and informs him that for his torment he has been awarded the Kingdom of Heaven. Immediately, by God’s command, violent winds swept away the doors and locks of Yegoryev’s prison. And Yegor himself, with the blessing of his mother, goes to Rus' to affirm the Christian faith. Driving through Rus', Yegor, in the name of God, reorganizes the earth, just as God once created it before the arrival of the “basurman”. By the command of Yegori, the dense forests part, the high mountains disperse, and cathedral churches rise in their place. In order to finally free Holy Rus' from “infidelism,” Yegor the Brave comes to Kyiv, enters into a duel with Demyanishch and defeats him.

“The Miracle of George on the Dragon” from an episode in the life of the saint turned into an independent plot and became a popular theme not only in ancient Russian literature, but also in the icon-painting tradition. St. George was depicted on icons not only as a young warrior in armor, with a spear in one hand and a sword in the other, but also as a rider on a white horse, beating a serpent with a spear. The plot of “George’s Miracle on the Dragon” on icons was often placed surrounded by scenes of the saint’s torment.

The Orthodox Church honors the memory of the Holy Great Martyr George the Victorious twice a year. People said: “There are two Yegories in Rus': one is cold, the other is hungry.” The first day - April 23 / May 6 - was established by the church back in the era of early Christianity in memory of the martyrdom of the saint. The popular names for this day are “Egoriy Veshny”, “Summer”, “Warm”, “Hungry”. The second day - November 26 / December 9 - was established, as noted above, by the Russian Orthodox Church in honor of the consecration of the Church of St. George in Kyiv in 1051. The peasants called this holiday “Yegory Autumn”, or “Winter”, “Cold”, and also “St. George’s Day”.

To St. George was always asked for help and intercession in the fight against the enemies of his native land, for protection from the machinations of the devil, as well as with a request for mental and physical health, and for the fertility of the land.

In the popular consciousness, the image of St. George was perceived ambiguously. On the one hand, according to life, apocryphal legends and spiritual verses, he was perceived as a serpent fighter and a “Christ-loving warrior,” and on the other hand, as the owner of the earth and spring moisture, the patron of livestock, and the manager of wild animals. In both cases, the basis of the image is the ancient pagan tradition, which was later influenced by Christianity. With the establishment of Orthodoxy in Rus', the image of St. George, reflected in ritual practice, took over the functions of pagan deities of pastoral and partly agricultural cults. In particular, St. Yegoriy became the successor of the Slavic fertility deity Yarila and the “cattle god” Veles/Volos.

Spring day of St. George was perceived in traditional culture as an important milestone in the agricultural calendar. The connection of the saint with agriculture is evidenced by the meaning of his name: George translated from Greek means “cultivator of the land.” Among the Eastern Slavs it has several variants: Yuri, Egor, Egor.

In the ideas of the peasants, St. Yegory acted as the initiator of spring, promoting the spring awakening and renewal of nature. In the folk calendar, with the day of Yegoriy Veshny, according to legend, real spring warmth came. Therefore, people said: “Warm Yegory begins spring, and Ilya ends summer,” “Yegory the Brave is winter’s fierce enemy,” “What is winter afraid of, but warm Yegory most of all,” “Egory has come and spring will not leave,” “Yuri brought spring to the threshold,” “Yegory brought warmth, and Nikola brought grass.” The peasants believed that Yegoriy began spring by “unlocking the earth” and “releasing dew into the white light.”

In the southern Russian provinces, as well as among Ukrainians and Belarusians, “Yurievskaya” dew was considered healing and fertile. On Yegoryev Day, they tried to drive the cows out into the field as early as possible, following the dew, which, according to popular beliefs, ensured the growth of the cattle and an abundance of milk. They said about Yuri’s dew: “There is dew on Yuri - the horses don’t need oats,” “Yagori’s dew will feed cattle better than any oats.” On this day, healers and ordinary women went to collect dew by running a cloth over the grass. The moisture squeezed out of the fabric was washed for health and beauty. The healers collected dew in reserve and used it to treat the evil eye, “the seven ailments.” In the Tula province there was a custom in the early morning to ride on the dewy grass. According to popular beliefs, anyone who rolls in the dew on His Day will be strong and healthy all year.

In the field of agricultural work, the day of Yegoriy Veshny was marked by late plowing, sowing spring crops, planting some garden crops, as well as a number of ritual actions that were aimed at ensuring the fertility of the land and obtaining a good harvest. Thus, in the Central Russian zone, where the first winter shoots appeared on St. Nicholas Day, peasants made processions of the cross to the fields, which ended with a prayer service addressed to St. George. In the Tver province, at the end of the prayer service, they rolled the priest on the ground, believing that this would produce high bread. In the Smolensk region, women on Yegoria went out into the field and rolled on the ground naked, saying: “As we roll across the field, let the bread grow into a tube.” Rolling, or somersaulting, on the ground is an archaic magical technique that, according to popular beliefs, imparts fertility to the earth. Here, in some places, after the prayer service, women remained in the field and had a joint meal. During the feast, a ritual action was also performed: one of the women tore off the scarf from the other and pulled her hair. At the same time, they usually said: “So that the owner’s life is tall and thick, like hair.”

In the Chembar district of the Penza province, young people walked around the fields on Yegoryev’s day in the late afternoon. They went to the field singing, and ahead of the procession walked a guy decorated with fresh herbs, who carried a large round pie on his head. After walking around the field three times, at the intersection of two, the youth lit a fire, near which a pie was placed on the ground. Everyone sat around the fire, and the division of the pie began. The girls immediately guessed by the amount of filling in a piece of pie: the one who had more filling, according to legend, was supposed to get married in the fall. While walking around the fields and on the way to the village, the youth sang special “Yuriev” songs of an agricultural nature:

Yuri, get up early,

Unlock the ground

Release the dew

For a warm summer,

To a lush life,

To the vigorous,

To the spicate one.

In the Vladimir province, male owners walked around the fields. They walked with images and willows in their hands. Having installed the icons near the arable land, they lit candles in front of them and sang:

Let us exclaim, brothers,

Holy kuralesa!

Give us, God,

Barley is mustachioed,

Spike wheat.

Cattle breeding rituals were no less colorful on Yegoryev’s day. Everywhere St. George was revered as the patron saint of livestock and shepherds. In some places he was even called the “cattle god.” The people believed: “If you bow to Saint Yuri, he will protect the animal from everything.” And the shepherds said: “Even if you keep your eyes open, you won’t be able to look after the flock without Yegory.”

Early in the morning the ritual of first driving the cattle to pasture took place. This ritual consisted of several actions, including the owners walking around the livestock in the yard, ritual feeding of the domestic animals, driving the cattle into the herd, the shepherd walking around the herd, the owners giving gifts to the shepherd, and a meal in the pasture of the shepherds, and sometimes the owners. The purpose of all these actions was to ensure the safety of livestock during the grazing season and to obtain healthy offspring from them.

In the Upper and Middle Volga region, if by Yegoryev's Day the grass had not yet appeared from under the snow, the cattle were driven out to Macarius (May 1/14) or to Nikola Veshny, but Yegoryev's Day itself was still celebrated as a holiday of shepherds. In the Russian North and Siberia, in such cases, on Yegoryev Day, a symbolic pasture was organized with all the main rituals. In some places in the Arkhangelsk province, instead of the rituals of the first cattle pasture on Yegoryev's day, children walked around the village. They, jingling cow bells, walked around all the huts, for which they received treats from the owners. In the southern Russian provinces, where cattle were often released to graze in early or mid-April, a ritual pasture was still held on Yegoryev's Day.

Like any magical event, the rituals of the first cattle drive were carried out before or during sunrise. In the southern Russian provinces it was believed that St. George himself travels around the fields early in the morning and therefore better protects the cattle that he finds in the field from diseases and wild animals.

Before sending the cattle to pasture, the owners, with magical objects and a spell, carried out a protective ritual of walking around the cattle in the yard. In the Smolensk region, the owner said: “Saint Yagoriy, father, we hand over our cattle to You and ask You, save it from the fierce beast, from the dashing man.” In some places, when walking around the cattle three times, a spell was uttered: “Lord, bless! I release a small animal into an open field, into an open field, into a green oak forest, under a red sun, under the moon of the Lord, under a heavenly chariot. From sunrise, the Queen of Heaven forces a golden tine from heaven to earth; from midday the Lord himself makes a silver tine; Mikola the Wonderworker from the west; Yegory the Victorious with a midnight bronze tyn. I ask and pray, save my little animal. Amen!"

Among the objects that in the popular consciousness were endowed with protective magical powers, when walking around they used bread, salt and an egg - Easter or specially painted for St. Valentine's Day. Yegoria in green. They were usually placed in a sieve, basket or bowl, sometimes in the bosom. Various metal objects were also used in the ritual. The ax was usually tucked into the belt. In the Pskov province, the owner, when walking around, in his left hand carried a bowl of grain, eggs, and an icon of St. George and a lit candle, and with his right hand he dragged his scythe along the ground. With this scythe he drew a magic circle around the animals, which was supposed to provide them with protection. In the Kostroma province, incense and coals were added to the icon, candle and bread.

In the Vologda province, the housewife, when walking around the cows, tried to shake the sieve with the icon, bread and egg so that the latter would constantly spin around the other objects. At the same time, she said: “As a testicle rolls around on a sieve, so the cattle would know the circle of its hut and go home, not stay anywhere.”

After going around the cattle three times, an icon was passed crosswise across the back of the cows, an ax was thrown over the back three times, salt or grain was sprinkled on the animals, eggs were rolled under the cow on four sides with the sentence: “Go to the field, / collect food, / run away from predators, / and run home!”

The bread with which the rounds were made was most often fed to livestock, believing that this would provide them with strength, health and offspring. The ritual of feeding was also a magical technique aimed at ensuring that the cattle stayed together and returned home after grazing. In some places, ritual bread was made on Maundy Thursday. In the Russian North, before kneading the dough, housewives took a tuft of wool from all the animals in the yard and baked it, depending on the local tradition, into one loaf for the whole animal or into small loaves for each animal. In many areas, cattle were fed grain; Usually, the grains of the last - last - sheaf were used for this.

Everywhere, when driving cattle from the yard, they were whipped with willow branches, blessed on Palm Sunday, and in Western Russian provinces - with ears of the first sheaf harvested last year, which were considered healing and were kept all year in the red corner behind the icons. In addition, on the threshold of the courtyard or at the gate to the street, the owners placed an icon of St. at the top. George, and a belt, an egg, a castle, an ax, a scythe, a frying pan and similar magical objects were placed on the ground, over which the cattle had to step.

In the Arkhangelsk province, the housewife, putting a yoke and a belt across the threshold of the barn and driving out the cows, said: “One end is in the wild, the other is in the house, don’t stay out for hours, don’t spend the night, read the house, know the hostess!” The power of the belt and lock, according to popular belief, lay in their properties: taking the shape of a magic circle and closing something. Magical powers were also attributed to metal objects: since iron cannot be eaten, if cattle steps over things made from it, predatory animals will not touch it. Similar significance was also attached to the stones that were placed on the threshold. Often an ax or pincers were left lying in the gate until the fall, otherwise, according to legend, the animals could attack the livestock. The housewives themselves, when driving cattle out of the gate, strictly observed the prohibitions of touching the cattle with a bare hand, as well as going out barefoot and with their heads uncovered.

In many places, an element of the ritual of the first pasture was the blessing of cattle near the church and sprinkling it with holy water after the prayer service and blessing of water. Only after this the herd was driven out of the village. Often a prayer service over the herd was served right in the pasture, before the shepherd's round. Early in the morning, the shepherd himself ordered a prayer service in the church, and after the service, walking through the village, he stopped at each yard, blew a horn or beat a drum, which gave the owners the signal to drive out the cattle.

The most important ritual of the first pasture of livestock was the shepherd's walking around the herd. He walked around the herd three times in the field, with prayer and magical objects: an icon of St. Yegoria, consecrated willow, eggs, bread, a lighted candle, a lock with a key, a knife, as well as with the attributes of shepherd's work: a staff, a whip, a drum or a horn. Mandatory for the ritual was also a “bypass” - a piece of paper with a prayer received by the shepherd from the sorcerer.

The hostesses were sure to honor and thank the shepherds for their rounds. To do this, they, festively dressed, went to the field to fetch the cattle and presented the shepherd with eggs, pies, meat, booze, and money as soon as the round was completed. Gifts, according to popular beliefs, had magical meaning. So, in the Novgorod region, a shepherd, having put food and money on a large dish, turned to St. Egor: “I give you bread and salt / And you are evil silver, / Keep my little animal, / In the field, in the green oak grove. / Save her from the creeping serpent, / From the mighty bear, / From the running wolf. / Put up a fence right up to the sky, / So that you can’t climb over, / You can’t step over it...” All this action symbolized the sacrifice of St. Yegor.

A festive meal was also held here. In some local traditions, the owners of the cattle sat down to eat with the shepherd. Here and there, several shepherds organized a festive feast from the collected food.

In the Kostroma province for the holiday in honor of St. George, the ritual of “calling out to Yegori” was celebrated, which was related to cattle-breeding rituals. Calling involved going around all the courtyards with the singing of special songs, reminiscent of carols in structure and meaning. The participants in the walk-through - “the greeters” could be women, young people (boys and girls together), only adult boys or boys and teenagers. A group of several people called out was led by a “mekhonosh”, who collected treats for singing songs. The detour was carried out late in the evening or at night on the eve of Yegor's day or the next night. The singing of “calling” songs often took place to the sounds of a drum - a shepherd’s musical instrument, as well as bells. At the end of the calling song, which had the character of a magical spell with an appeal to St. Yegor about the protection of livestock, the hailers demanded remuneration for their labors. In gratitude for the treat, the following wishes were granted:

God bless you all

Christ put on

Two hundred cows

One and a half hundred bulls,

Seventy heifers

Lysenkikh,

Krivenkikh,

They're going into the field,

Everyone is pushing around.

They are coming from the field -

Everyone is playing.

If there was no reward, the hailers wished the owners misfortune and misfortune: “Whoever does not give an egg, / All the cattle from the yard / will be given to the bear.” Or:

Thank you, auntie,

On a bad alms!

God bless you

Live longer

Yes, make more money -

Lice and mice

Cockroaches from your ears!

After the round, the participants divided the collected food among themselves or had a common meal and ate it.

According to the peasants, St. Yegory was the protector of all livestock, but in some places he was revered primarily as the patron saint of horses, which may be due to the peculiarity of the saint’s iconography - his frequent depiction on horseback. Among the Russians in the Angara region, Yegoryev Day was called a horse holiday. In the Vyatka province, April 23 was considered horse name day. The peasants tried to treat the horses - to give them “hay up to their knees, oats up to their ears!” In many places there was a ban on harnessing horses and working on them on the day of the holiday. In the Arkhangelsk and Vologda provinces, on Yegor’s Day, horses were driven to a chapel or church and sprinkled with holy water. In some places, horses were required to be bathed on this day. In the Ryazan region on the evening of Yegoryev Day, the guys made a costumed “horse”: two guys were covered with a canopy, one of them picked up a bag of straw on a stick, depicting the head of an animal. The shepherd sat on the “horse” and played the pity. Accompanied by fellow villagers, the “horse” walked around the entire village and headed beyond the outskirts, where the “horse” from the neighboring village also arrived. A fight began between them. The mummers “laughed” and fought until one of the “horses” won, destroying the other.

Yegor the Brave was considered the patron and manager of not only domestic animals, but also wild animals. They said about the saint: “All the animals, all living creatures are at George’s fingertips.” The people believed that on the day of the holiday he went into the fields and forests and gave orders to the animals. This idea was especially associated with wolves, which were popularly called the “dogs” of St. His-riya. The spiritual verse about George’s struggle with Tsar Demyanishch tells how the saint takes wolves under his power: one day, when Yegor was riding through the forest, a wolf ran out to him and grabbed his horse’s leg with its teeth. The saint pierced the wolf with a spear, but the beast spoke in a human voice: “Why are you beating me when I’m hungry?” - “If you want to eat, ask me. Take that horse, it will last you two days.” Since then, every year on the eve of the holiday the saint gathers wild animals in a designated place and assigns each one prey for the year. Yegory orders them and eats only what is “commanded”, “blessed by Saint Yegory”. That’s why people said: “What the wolf has in its teeth is what Egoriy gave”, “Without Yuryev’s orders, even the gray one will not have enough”, “What the wolf has in his mouth, and he also lives according to the law: whatever Egoriy says, he will decide everything.” -xia." In winters, when many wolves multiplied, the peasants said that St. Egory.

In the Middle Volga region, owners tried to find out in advance which animal St. Yegory was doomed to be eaten by wild animals. To do this, before the first pasture of cattle, the eldest in the family went out into the meadow and shouted: “Wolf, wolf, tell me, which animal do you like, what was Yegor’s order for you?” Returning home, he went into the sheepfold and in the dark grabbed the first sheep he came across. She was considered doomed. This sheep was slaughtered and thrown into the field, head and legs. The rest of the meat was cooked and treated to the shepherds, and they also ate it themselves. In the Oryol province there was a belief that Yegoriy gave the wolf only those cattle whose owners forgot to put a candle in the church for the image of the saint on the day of the holiday.

According to traditional beliefs, the safety of the herd during the grazing season largely depended on the professional and human qualities of the shepherd. The peasants believed that St. Yegory himself makes sure that the shepherds observe standards of behavior, including moral ones, and punishes the evil, careless and dishonest. Thus, in the southern Russian provinces there was a widely circulated story about how St. Yegory ordered the snake to bite the shepherd, who sold the sheep to the poor widow, and attributed the blame to the wolf. Only when the shepherd repented of his actions and lies, St. Yegory appeared and healed him.

In some places St. Yegor was especially revered by hunters, considering him their patron. On Yegoryev's day they turned to the saint: “Yegory the Brave, Holy is my helper! Drive the white beast, the hare, through my traps through the clean fields; to your servant of God (name), drive the white beast, the hare, from all four sides.” Every time the hunt itself began with the pronouncement of this conspiracy.

In many localities, Yegoryev Day was celebrated as a big holiday - for two or three or more days, which were marked by brewing beer and visiting relatives and neighbors. In the Novgorod and Vologda provinces, the celebration began with the owner going to church in the morning with wort, which was called “kanun”. During mass he was placed in front of the icon of St. George, and then donated to the clergy. Where Yegoryev's day was a patronal holiday, it was celebrated for a whole week.

In Siberia, on the eve of the holiday - “Yegory's Eve” - beer was brewed by the whole world. In the morning, the peasants went to church for service, and then drank “eve beer” together. In the house of the church warden, women and girls gathered at the table, and in the courtyard - men and boys. All visiting guests were also given beer. Drinking a measure of beer, everyone left money, which went towards buying candles for St. Yegoria and for the needs of the church. On the day of the holiday, the community ordered prayer services, which were served in squares, fields, and also in barnyards. After the prayers, they finished the eve beer, and in each house, men and women were seated at separate tables, arranged in different halves of the hut.

If agricultural work intensified with Yegoriy Veshny, then Yegory Zimny finished his household chores. In folk tradition it was not marked by any important ritual actions. Only in some places, ritual actions of a pastoral nature were timed to coincide with the autumn day of Yegor, as well as the spring day. So, for example, in the Ryazan province, housewives on this day baked cookies called “horses”. Groups of guys gathered him from each yard, going around the village. After the round, they went to the field, where they left cookies as a sacrifice to the saint with the sentence: “Merciful Yegory, do not beat our cattle and do not eat. Here they brought you horses!”

In medieval Rus', this day had a special legal significance. In the 15th century, the Code of Law of Ivan III established the week before and the week after St. George’s Day as the period for the transfer of peasants from one owner to another. The timing of this transition specifically to Yegor Zimny was due to the fact that by this time the peasants had completed agricultural work and paid duties for the land to its owners. This right was eliminated by Boris Godunov at the beginning of the 17th century, which led to the final enslavement of the peasants. There is a popular saying about this event: “Here’s Grandma and St. George’s Day.”

| |